Good Grief: Middle Grade Authors Normalize Loss

Explaining why they write about children who are grieving, authors describe experiences from the loss of a family member to concerns about gun violence.

|

Illustration and SLJ October cover below by AurÉlia Fronty |

There may be no experiences more universal and specific than loss and grief. Loss can, and will, happen over and over. Grief can overcome anyone, at any age, at any time. By age 18, more than eight percent of children will have lost a parent or sibling, according to author and therapist Jess Redman. By 25, that rises to 20 percent, according to the National Alliance for Children’s Grief.

Grief is a natural response to death and loss. It’s stressful, emotional, and can take a toll on mental health and physical well-being.

In the last several years, middle grade books that grapple with grief have flourished, perhaps reflecting the deaths of friends and loved ones that many experienced since the start of the pandemic, or as part of a cultural shift that is bringing subjects like grief and mental health out of the shadows. As of February 2022, at least 204,000 U.S. children and teens had lost parents and other in-home caregivers to COVID-19—more than 1 in every 360 youth, according to COVID Collaborative, a group that is raising awareness and support for COVID-bereaved children.

It’s a big topic that can be challenging for young people to talk about, particularly middle graders. Most kids this age don’t yet have the tools to help process enormous loss or the perspective to put it into context. That’s where fiction can help. As author Emily Barth Isler says, “The middle grade years are a great time to start conversations with kids and the grown-ups in their lives to help them see that we cannot avoid those who are grieving, and, in fact, we should reach out to them.”

Also read: "8 Board Books and Picture Books for Día de Muertos"

Adults and educators often talk about naming and working through “big feelings” with young children, including those of loss and grief. But that affirming approach often wanes as children get older. For people of any age, there is power and comfort in being able to name emotions, especially something as difficult, confusing, and at times scary, as grief. “If we want our children to feel safe and to grow into emotionally intelligent adults, they need to know that death is a part of living,” says author K. A. Reynolds. “It’s OK to be sad, because it hurts to let go.”

|

Clockwise from top left: K. A. Reynolds, Emily Barth Isler, Christina Li,Lisa Stringfellow, Gary D. Schmidt, and Jess Redman |

Inspirations and influences

Middle grade authors who center grief often don’t have to look far for inspiration. In Reynolds’s Izzy at the End of the World (HarperCollins/Clarion, 2023), 14-year-old Izzy Wilder, who shares Reynolds’s identities as white, queer, and autistic, finds herself, a year or so after her mother’s death, almost all alone in the apocalyptic wake of an alien invasion.

COVID-19 hit while Reynolds was revising the manuscript. Her family also received an eviction notice, and her husband, Bob, was diagnosed with stage-four cancer. Reynolds finished the revision sequestered in a hotel. “I wrote and cried my heart out,” she says. She turned in the edits, went home, and received feedback from her editor. “Then,” she says, “my Bob died.”

There is no good time to lose a loved one. But to Reynolds, editing that book amid those events seemed like a monumental task that also informed the story. “My characters were grieving, and so was I,” she says. “My characters needed hope, and oh, so did I. Izzy and I clung to each other for dear life.”

Isler’s AfterMath (Lerner/Carolrhoda, 2021) tells the story of 12-year-old Lucy, whose brother, Theo, died eight months ago from a congenital heart defect. Her family moves to a new town, one where Lucy’s fellow students survived a school shooting four years ago. Lucy, who, like Isler, is Jewish and white, is shocked by how easily her peers talk about the tragedy. She bottles up her own grief, like her parents do.

What motivated Isler to write this story? An activist working for safer gun laws, she says, “I was having trouble processing the realities of gun violence in America and struggling with how to cope with sending my kids to school and out into the world.” Isler also figured that if she was thinking about this issue, then surely middle schoolers, who practice lockdown drills and live with the epidemic of mass shootings, were, too. Taking a cue from her classmates, who easily discuss details of their shared tragedy, Lucy begins to learn how to talk about her brother and her loss.

While writing The Miraculous (Farrar, 2019), Redman was working as a therapist for adolescent clients and experiencing a difficult pregnancy. In her story, 11-year-old Wunder believes in miracles—until his baby sister dies at eight days old. “As a therapist, it was important to me to write a story that spoke to the reality of how kids experience loss and to show that there are many paths to hope and healing,” Redman says. Wunder, whose grief makes him feel as though parts of him have been erased, finds healing in connections with others who have lost loved ones.

In Lisa Stringfellow’s A Comb of Wishes (HarperCollins/Quill Tree, 2022), the main character, Kela, is grieving the loss of her mother, who died in a car crash. “I wanted to write a story that affirmed those experiences and showed a child who struggles but is surrounded by caring adults who support her,” says Stringfellow, a teacher to some students whose parents have died. Kela, who is Black, like Stringfellow, is fortunate to have that support. Her best friend may not know quite how to help. But she supports Kela by saying, “‘Whatever you’re feeling—we don’t have to talk about it. But we can if you want.’”

Gary D. Schmidt tackles the almost unthinkable loss of both parents at once in The Labors of Hercules Beal (HarperCollins/Clarion, 2023). For a school assignment, seventh grader Hercules is tasked with performing and reflecting upon the mythological 12 labors of Hercules. He also finds himself processing the deaths of his parents, who were killed by a drunk driver. On choosing to center grief in this story, Schmidt says, “We can at least redeem that burden a little by authentically showing others—in this case, young readers—what grief is like, how it is normal and at times necessary, and how it is lived through.”

Coping

Support in varying forms is vital as kids try to cope and slog through the mire of grief and its many stages. The characters in these books cope in different ways. Some have more support than others, and some find ways to feel connected to their loved ones after death.

Ruby, the 13-year-old Chinese American protagonist of Christina Li’s Ruby Lost and Found (HarperCollins/Quill Tree, 2023), has recently lost her beloved grandpa. She feels stuck in her grief, alone, and unable to talk to anyone about her feelings, especially her guilt. She thinks that if she had made different choices, she might have saved Ye-Ye from his stroke.

“Ruby is not coping with her loss at all. She is scattered, distraught, and unsupported by family and friends,” says Li. “It is only after spending her summer with her grandmother, and making new friends, that she learns that there can be space made around her grief.”

“We all need someone or something to hold on to amid great loss,” notes Reynolds. For Izzy in Izzy at the End of the World, her mother’s death triggers depression and anxiety. She finds comfort in her dog, Akka, and in sensing her mother’s spirit. Storylines like these “add a necessary layer of love and healing to the book,” Reynolds says.

Acting like everything is fine is another common response to loss. Stringfellow’s Kela withdraws into sadness but doesn’t want anyone to worry about her. “I talked with a friend who is a social worker to get feedback on Kela’s behaviors and feelings,” Stringfellow says. “The adults in Kela’s life support her by keeping the lines of communication open and giving her time and space.”

Isolation can also complicate grief, and Redman worries about that impact on children. “Over and over, I’ve found that there is healing in connection for my young clients,” she says. “A teacher who checks in, a friend who doesn’t shy away from talking about the deceased loved one—these consistent expressions of support are invaluable to a bereaved child.” Kids may think they can’t talk about what they’re feeling; they may be embarrassed or ashamed, and, like Kela, push people away.

Sometimes unexpected connections can help grieving children, such as when Wunder, in The Miraculous, is befriended by extroverted, cape-wearing classmate Faye Ji-Min Lee. Together, they spend time with a mysterious older woman who lives by a cemetery where Wunder’s sister and Faye’s grandfather are buried. Wunder ends up delivering letters from the woman to people in town, addressing their losses.

“He starts to understand how universal the experience of grief is and also how many different ways there are to grieve—from grief groups to religious ceremonies to serving others to therapy to memorial projects,” Redman says. Through the letters and maybe a few miracles, the story ends in the cemetery with townspeople gathered to remember their loved ones.

Rituals to honor and celebrate lifeIn many cultures and religions,processing the loss of a loved one can include rites and rituals of celebration and honor, such as parades, dancing, offerings, food, bright clothing, singing, prayer, and the welcoming back of spirits. Customs that recognize and celebrate loved ones who have passed include Ghana’s elaborate fantasy coffins; lively jazz funerals in New Orleans; China’s Qingming festival, which involves tending to ancestors’ graves and leaving offerings; the Balinese Ngaben cremation ceremony; the Buddhist and Taoist Ghost Festival; the 16-day Hindu Pitru Paksha; and the Mexican holiday DÍa de Muertos. These observances and customs show that the complicated process of grieving can include joy, gratitude, and celebration, focusing on ways to see death as a gentle, joyful transition, not just an ending.

|

Offering hope

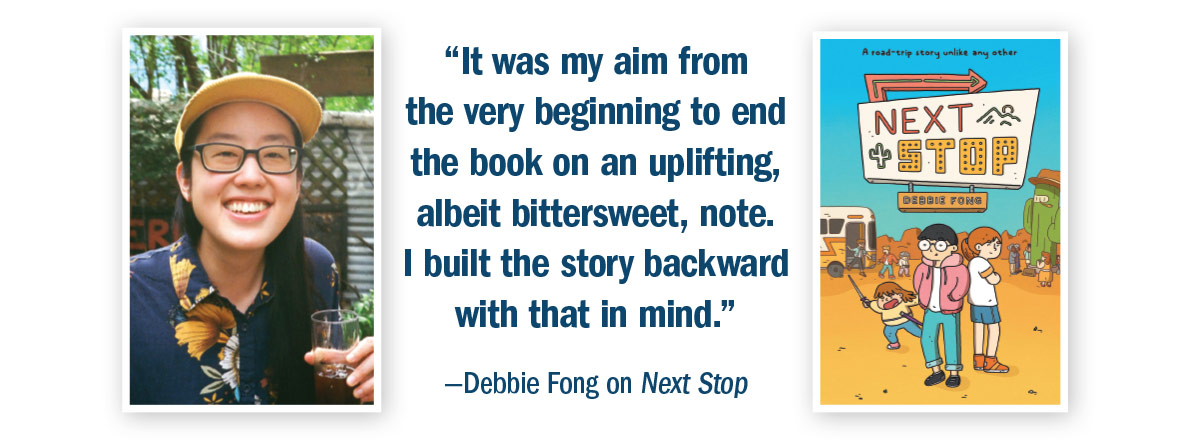

A hallmark of middle grade books is offering hope to both the characters and the readers, which can be particularly challenging with heavy topics. But that was a priority for Taiwanese American Debbie Fong, author and illustrator of the graphic novel Next Stop (Random House Graphic, Mar. 2024). Her main character, Pia, is still reeling from the loss of her younger brother, who drowned while she was supposed to be watching him. Next Stop recounts the months after the accident and the good times before, showing how Pia and her parents have been affected. It’s a painful story, filled with guilt and a depressed mother who can’t help but blame Pia. “It was my aim from the very beginning to end the book on an uplifting, albeit bittersweet, note,” Fong says. “I built the story backward with that in mind.”

Stringfellow wrestled with incorporating hope in A Comb of Wishes, which has magical elements. “An earlier version of the novel ended with a ‘happily ever after’ in which Kela’s mother’s death never occurs. But it was unsatisfying, because that’s not the way death works in our real lives,” Stringfellow says. “We can’t just wish it away.”

She eventually found a way to balance the reality of loss with the reassurance that Kela will be OK.

Learning to live with a new reality is another important message. Loved ones die, but those who are left persist. Li points to a hopeful light in the darkness of loss by showing that “there can be continuation of love for someone after you lose them.” Similarly, Stringfellow hopes her book and others “remind children that the ones who have left us will stay in our hearts,” that there is still love and joy in their lives.

Characters also cope with the help of therapy, support groups, school counselors, and family doctors. Isler says, “My amazing editor, Amy Fitzgerald, encouraged me to talk more and more about therapy. We got almost all my characters into therapy by the end of the book!”

Schmidt has written many books with characters who are no strangers to grief. He hopes readers identify with them and see ways to cope and heal. But critically, he notes, novelists aren’t offering step-by-step guides to grief.

“The novelist is more like the caring adult who stands beside you, who affirms that what you are experiencing is real and normal, and who says, through detail and image and language that is laboring its way toward truth, ‘I know what it feels like. I’ve been there. You’re right—it’s really hard and really messy. Sometimes it’s terrible. I am surviving. You are too. You will too.’”

Stories that reflect real life

Some may question why authors choose to write sad or serious books when life is hard enough. They may believe in “protecting” readers, as though these kinds of events don’t happen regularly to real children. “I try to convey to the parents of my students the importance of kids reading all types of books, including the sad ones,” says Stringfellow. She knows these stories can help readers process their feelings and better understand what someone they know may be going through.

“As a therapist, I have often encountered this sort of wishful adult thinking,” says Redman. “Books [with] difficult topics can start the conversations we should be having with kids.”

Fong concurs. “The best stories are a reflection of life, with all of its messiness, pain, and beauty.”

“Who wouldn’t wish that we could preserve our children in a world of innocence for as long as possible?” Schmidt says. “Stories are the bulwarks young readers build into their souls against the onslaught of the real world.”

Isler understands there’s no hiding from these realities. “So many parents [wrongly] tell me that their kids don’t know about the existence of gun violence,” she says. “We all need a reminder that our kids are facing different realities than we did a generation before. We must adjust our conversations accordingly.”

These authors show readers that grief is not something to “get over,” but something to adapt to, to work through. It’s OK to not know how to feel, what to do, or what to say. “There can be space for it all: for the comingling of grief, love, healing, and loss all at the same time,” as Li says.

And while children in the throes of grieving might not believe it, they will be OK. As Schmidt’s character Viola says to Hercules, “‘OK is enough for now.’”

Amanda MacGregor blogs at “Teen Librarian Toolbox.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!