From 'Hamlet' to Hannah: How Understanding ADHD Made Me a Better Writer

The debut author explores her experience growing up with ADHD, and how it informed her novel Hannah Edwards: Secrets of Riverway.

“The point is ADD makes children restless and easily distracted.”

“The point is ADD makes children restless and easily distracted.”

This line is not from a psychological resource or a parenting advice website. It was said by Principal Skinner in a Simpsons episode where Bart is diagnosed with ADD—now commonly referred to as ADHD, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Bart fits the popular depiction of ADHD: he fails his courses, distracts other students, talks out of turn in class, and is generally a menace to the school population. Similarly, at the psychiatry clinic where I received my diagnosis, I was asked to provide “proof” of my ADHD, like comments from teachers about how I was easily distracted and talked too much, or courses where I performed poorly. This infuriated me and compelled me to rewrite the conventional narrative of ADHD portrayed through characters like Bart Simpson. Why? Well, because I, Ashley Hards, have always been—and will always be—a pleasure to have in class.

My Journey with ADHD

My journey with ADHD was unconventional. At age five. I haughtily approached my mother and demanded that she talk to my teacher. I was bored out of my mind.

By the time I was eight, I told my mother that I was not going to school anymore, because:

1) it was too boring,

2) I already knew everything (bold claim),

3) I could get the work done in an hour.

My parents had me evaluated, and I was declared a “gifted” student. My new gifted title came with some perks: an Individual Personalized Plan (IPP) that allowed me to study more advanced material.

I believe this IPP—combined with a fundamental misunderstanding of how ADHD presents, particularly in women—is why I was not formally diagnosed with ADHD until I was 22. The symptoms were all present, just not in the ways people assumed. I had the desire to speak all of the time—I just compensated for it by always being the first student to raise their hand. I wasn’t visibly distracted—but I was writing short stories instead of taking notes in class. And, most importantly, my issues with paying attention never affected my grades—the perfectionism that often accompanies ADHD always kicked in and saved the day.

Just because a struggle is not visible does not mean that it doesn’t exist. My issues with ADHD were internal. And, as I progressed into the less structured university environment, the consequences of this internal struggle became even more significant. The most obvious presentation of this struggle was procrastination—a trait that affects many people with ADHD. The work that I was given seemed so simple that I couldn’t motivate myself to do it. I knew that I was creating problems for myself. What was wrong with me?

My diagnosis gave me a name for my schoolwork paralysis: executive dysfunction. And, most importantly, my diagnosis shone a light on my overly harsh view of my own work—a low sense of self-worth that was often impacted by rejection sensitivity dysphoria (RSD). Rejection sensitivity dysphoria occurs when an individual has an extreme experience of emotional pain when encountering perceived rejection. In the case of my writing, the prediction of experiencing academic rejection prevented me from even starting my work.

Enter the Danish Prince

When I realized how overblown my reactions to simple things could be, I turned to my companion, Hamlet: “O that this too, too sullied flesh would melt, / Thaw and resolve itself into a dew."

“How melodramatic,” I thought. “How like me.” And that gave me an idea.

I reread Hamlet shortly after my diagnosis for the practical reason of using it as a possible source for my master’s thesis. I didn’t end up including it in my thesis. Instead, I found something far more fruitful: a companion for understanding my ADHD. Hamlet’s extreme reaction to grief; his desire to put off important tasks (revenge) until things were “perfect”; his impossible standards (set by his foil, Fortinbras); and his rejection and frustration with his own psychological limitations all struck a chord with my understanding of neurodivergence. Unlike Bart Simpson, Hamlet was a companion I could (mostly) relate to.

But Hamlet had his drawbacks: his frequent misogynistic comments isolated me from fully aligning myself with him. That’s where Hannah Edwards came in.

Hannah Edwards and ADHD

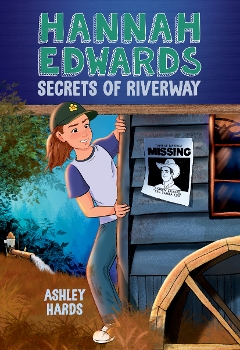

Hannah, the title character in my new middle grade book, Hannah Edwards Secrets of Riverway (Fabled Films Press, September 2024), is similar to Hamlet in myriad ways. Spoilers to follow. Hannah also has an extreme reaction to grief, denying her father’s death until it becomes impossible to refute. Like Hamlet, she experiences a desire for certainty: she wants to be sure that the ghost is her father, that the water pump he warns her about is real, that his brother Fergus is behind everything evil. She has a firm sense of justice, reacting strongly to betrayal. Hannah, too, has her moments of self-deprecation, especially when it comes to academic success.

Hannah is not me. She is more distractible. Fair enough—she has big things on her mind. Her teachers notice her distraction, and, ultimately, Hannah is lucky to receive an early diagnosis for whatever neurodivergence she experiences. Nevertheless, I feel a closeness to her. Her journal entries about being bored in class were taken from old portions of my personal notes. Hannah’s experience of executive dysfunction when writing her book report is the most emotionally charged portion of this novel for me, because it was actually written when I was frustrated about not being able to write the Hannah Edwards manuscript. Now that's Shakespearean.

I am not trying to criticize anybody who has had the Bart Simpson ADHD experience—anybody who did struggle in school or received teacher reprisal for their behavior. My hope is that Hannah will provide a more nuanced depiction of neurodiversity. One that perfectionist students can relate to, and other students can understand. One that shows that struggling internally is okay, and there are always ways to get help. And, especially, one that shows that you can have ADHD and—like me, Ashley Hards—can still be a pleasure to have in class.

Ashley Hards was declared to be “gifted” at age 8 and was diagnosed with ADHD at age 22. When forced to sit still in class, she found books and writing to be the most engaging subjects, especially Shakespeare. She received both her BA and MA in English Literature from McGill University, where she now teaches writing and continues her research on Shakespeare and ritual. She grew up in the city of Calgary, Canada. This is her debut.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!