Unnatural Selection: More Librarians Are Self-Censoring

In the middle school library where Elaine Fultz used to work, a complaint was launched against Lauren Myracle’s “Internet Girls” series (Abrams), which includes titles, such as ttyl and ttfn, that are among the most challenged books of 2009 and 2011.

In the middle school library where Elaine Fultz used to work, a complaint was launched against Lauren Myracle’s “Internet Girls” series (Abrams), which includes titles, such as ttyl and ttfn, that are among the most challenged books of 2009 and 2011.

But Fultz, now the district library media specialist for the Madison Local Schools in Middletown, OH, knew that girls who otherwise weren’t interested in reading were drawn to these books.

“I defended them with reviews and testimonials from both teachers and students that these books were gateways for reluctant (girl) readers, much like ‘Diary of a Wimpy Kid’ is for boys,” Fultz says. “There were ‘non-readers’ who read these books and loved them and went on to read books in traditional format.”

The books remained in the collection, but as a concession to those who complained, Fultz had to add a “circulation note” in the school’s library management system indicating that the books could only be checked out by eighth graders—a compromise Fultz didn’t support. “Restricted sections and labeling are a form of censorship,” she says.

Such moves to limit students’ access to titles that might stir controversy, however, are on the rise, according to the results of a new Controversial Books Survey conducted by SLJ earlier this year that also addresses self-censorship.

School libraries at all levels are more likely than they were eight years ago to place content labels on books or to have restricted sections for books containing mature content, a data comparison to a 2008 SLJ survey on collection development and self-censorship revealed. The practice of using content labels has increased the most at the elementary level, from 18 to 33 percent. At the middle school level, 27 percent of respondents say they currently use labels, compared to 10 percent in 2008, and in high school, the number has increased from six to 11 percent.

School libraries at all levels are more likely than they were eight years ago to place content labels on books or to have restricted sections for books containing mature content, a data comparison to a 2008 SLJ survey on collection development and self-censorship revealed. The practice of using content labels has increased the most at the elementary level, from 18 to 33 percent. At the middle school level, 27 percent of respondents say they currently use labels, compared to 10 percent in 2008, and in high school, the number has increased from six to 11 percent.

Ten percent of elementary librarians, 12 percent of middle school librarians, and six percent of high school librarians say they currently have a restricted section for books with mature or potentially controversial content.

More school librarians also report that they have decided not to purchase a book because it includes subject matter that could be controversial, such as sexual content, profanity, or other “non-age appropriate” material. More than 90 percent of elementary and middle school librarians say they have passed on purchasing a book for those reasons. Among those working in high schools, the number drops to 75 percent.

A third of librarians working in elementary and middle schools and a quarter of those in high schools say they are confronted with these decisions more than they were a few years ago.

“I used to not buy books where there was sex, but then I thought, ‘if it [involves] a ghost that's 240 years old, I guess it's OK,’” says Sara Stevenson, librarian at O. Henry Middle School in Austin, TX. “Then I had to change it to, ‘OK, as long as it's just implied.’ Then I had to change it to, ‘OK, as long as it's not too graphic.’ Then I had to let some more graphic ones through because the kids wanted them and they had great reviews. Now there are more and more books with gay sex, so where do you draw the line?”

SLJ’s Controversial Books Survey was emailed to a random sample of school librarians in March. Respondents remaining anonymous, and 574 librarians responded. Eighty-three percent of the respondents work in public schools, 15 percent are in private schools, and two percent designated “other.” Almost half—46 percent—work in suburban schools, 21 percent in small towns, 19 percent in urban schools, and 14 percent in rural ones.

Challenges hard to predict

More than 40 percent of librarians responding to SLJ’s 2016 survey say they have personally faced a book challenge. Librarians working in schools on the West Coast are most likely to answer “yes” to having directly faced a challenge (49 percent). Librarians in the Northeast are the least likely to answer “yes” (38 percent).

Joan Bertin, executive director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, says that the overall results “pretty much confirm our experience dealing with these complaints for 40-plus years.” However, she adds that the percentages by region don’t seem to reflect her knowledge of book challenge activity. State-by-state results might be more telling, she says, noting that challenges are often launched in conservative pockets within states.

Fifty percent of librarians working in urban schools say they have faced a book challenge, compared to 46 percent in rural institutions, 42 percent in suburban districts, and 32 percent in small towns.

The vast majority of challenges come from parents, ranging from a high of 92 percent at the elementary level to 80 percent in high schools. Administrators and teachers are the next most likely groups to formally challenge a book; these numbers are around 10 percent.

The vast majority of challenges come from parents, ranging from a high of 92 percent at the elementary level to 80 percent in high schools. Administrators and teachers are the next most likely groups to formally challenge a book; these numbers are around 10 percent.

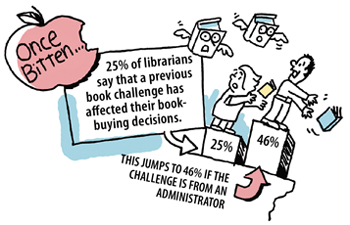

A quarter of librarians who have faced challenges say the experience affected their future decisions about buying books.

“We can be our own worst enemies,” says Stevenson, who faced her first formal book challenge this year when two mothers at her school objected to John Green’s Looking for Alaska (Dutton, 2005), which has been frequently challenged in schools. “I fear I will be less brave now that I've had to go through the ordeal of a formal challenge.”

Stevenson adds that she passed on Andrew Smith’s Grasshopper Jungle (Dutton, 2014) and a few other titles, recommending them for the high school instead.

“No librarian wants to be branded publicly as a corrupter of youth. That is what we're up against,” Stevenson says. “It's really a sad situation. I hope I don't have to leave the profession I love and excel at, but I can only make so many compromises.”

Bertin adds that self-censorship could explain why the percentages of librarians reporting that they have faced a challenge seemed to her to be low in some parts of the country. “If the people responsible for selecting books are preemptively self-censoring, you’re not going to see challenges,” she says.

Seventy-five percent of the respondents say their future decisions on books were not affected by previous challenges. “I’ve found that you cannot predict challenges,” one librarian says in response to an open-ended question on the survey. “The books that have been challenged during the 18 years I’ve worked in our school district came out of left field.”

Another respondent sees challenges as an incentive to include the book in her own collection. “If a book is challenged anywhere in the school district, I make a point to purchase it for the library,” this middle school librarian says.

Seventy-seven percent of the respondents—81 percent in public schools and 59 percent in private ones—say that their school has a formal book challenge procedure. Those percentages are too low, says Jamie LaRue, director of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Office for Intellectual Freedom and executive director and secretary of the Freedom to Read Foundation, an organization promoting free speech and defending libraries facing such challenges.

“This is the piece that can be fixed. One hundred percent of schools should have a reconsideration policy,” says LaRue. He adds that librarians working in schools without an official procedure should strongly advocate for one. “You don’t have to wait for a crisis to do something. It makes the controversy manageable.”

A deeper problem related to the survey findings, LaRue says, is that schools and districts that have cut librarian positions no longer have someone on site prepared to respond to a controversy over a book. Staff members without formal training are “not equipped to deal professionally with the challenge,” he says.

Fultz says that in her experience, library aides will not purchase anything controversial.

Policies guiding decisions

Policies guiding decisions

The survey questions also explored the procedures librarians use to decide whether to purchase a book. Most say that they rely on reviews from other librarians and read potentially controversial books for themselves. They also consider reviews by SLJ, Booklist, Kirkus, Common Sense Media, and other organizations.

Those reviews often come into play when someone launches a formal challenge against a book, the survey results show. Thirty-seven percent of librarians working in high schools, 26 percent of middle school librarians, and 30 percent of those working in elementary schools say that their library’s book selection policy requires them to consult professionally sourced reviews in case a purchase is challenged.

“Our system requires two professional reviews,” one librarian writes. “I will follow those, and if I am still uncertain, I will read the book myself or ask another teacher or two to read [it].”

Some say their book-selection policy recommended using reviews, but didn’t require it. Forty-four percent of elementary and middle school librarians and 32 percent of high school ones say they don’t have a formal policy on choosing books.

Appropriateness for middle school

Middle school librarians especially say it is becoming harder for them to determine whether the content of a book is appropriate.

“Middle school is a tricky age group to serve, so I try to make sure that the books will speak to my students’ concerns in a way they can comprehend,” one K–8 librarian writes. “My worry is that books with content that is too mature won’t help them make sense of complex issues but instead feed negative social or other dynamics.”

Another librarian working in a middle school avoids most young adult books, and a third says, “In my professional judgment and considering our selection policies, explicit sex, violence, or drug use are not appropriate topics for a middle school audience.”

At times, simply talking with students about their choices can keep a parent’s concern from escalating toward a formal challenge, librarians say. Fultz, who selects books for a seventh through 12th grade school library, says that when a junior high student wants to check out a book that she feels is more suited to a high schooler, she asks the student to consider whether his or her parents “would be uncomfortable with the content and to ‘make a good decision for yourself as a reader.’”

When a manga series was questioned by a parent in her district, Fultz asked the student to respect his family’s wishes and not check out those books. The series was never removed from the shelf or labeled in any way.

Unsuccessful challenges

Unsuccessful challenges

Sometimes, book challenges don’t get very far, librarians’ survey responses show. A few say that they have faced verbal challenges from parents, but parents did not follow through with the formal procedure. In the Atlanta (GA) Public Schools, where librarian Shanna Miles works, for example, the policy requires those who want to challenge a book to read it in full. “Because of that, we haven’t had that many challenges,” she says. Another librarian reports in the survey that the school’s principal simply checked out two controversial books and kept them for eight months.

Pat Scales, former chair of ALA’s Intellectual Freedom Committee and author of SLJ’s Scales on Censorship column, agrees that most of the time, a challenge does not lead to a book being banned. “Good conversation with a parent, or any challenger, usually ends with reason, and without further actions,” she says.

Some responding librarians don’t restrict students from books, but do shelve titles by age level, and the majority don’t separate books into special sections.

School libraries that have restricted sections don’t always have clearly defined rules about checking out those books. Some create ambiguous barriers. “Inside the cover I will write, for example, ‘profanity,’ and I ask for a note from the parent, although it is not required,” one librarian says. Another notes that students only need to provide a verbal “yes” that they have asked their parents if they can check out a book with a YA label.

Bertin adds that when people casually suggest that school districts rate books the way movies or video games are rated, it raises First Amendment issues. “Government officials can’t adopt ratings to try to regulate access,” she says. “It’s different when a private company wants to put a tag on its product.”

Labels and restricted sections have been found to legally violate students’ First Amendment rights. In a 2003 case, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas ordered the school board for the Cedarville (AR) School District to stop requiring students to obtain permission from their parents if they wanted to read 'Harry Potter' books.

“Minors also have rights,” says LaRue, adding that it’s important for students in increasingly diverse schools to find books that reflect their heritage and experiences. “It’s the responsibility of the library to serve everyone.”

At the urban Atlanta high school where she works, Miles says that many of her students, who range in age from 14 to 21, don’t have access to public libraries because they or their parents don’t have a car or can’t reach public transportation. They might also not have Internet access at home.

“At that point, you are the creator of the known world. If it cannot be found in your collection, it simply does not exist,” she says. “Would you have your LGBT students believe that they do not exist? Would you allow victims of sexual abuse to believe that they are the only people to ever have that experience?”

Miles says she purchases books with material that might be controversial “because my students are living in an environment that exposes them to the realities of life that many people would like to forget, and they need texts that offer them a mirror to their own life and a window into the lives of others who have gone through things that they have and have overcome them.”

Placing labels on books or isolating them in some way is also ineffective as it only entices students, Scales says. “They gravitate to what they view as ‘forbidden.’” On the flip side, she adds, “It also sends the message that ‘something is wrong’ with the book.”

Scales also recommends telling students to put down a book they don’t like. “Students will most often reject what they aren’t ready for,” she says. “When we free them to read, we also free them to reject."

Spot illustrations by Mark Tuchman

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Renee MA

I always face book challenges in my working library, but not from parents, most from teachers. Actually, our library collection divided into elementary and middle school section. And they have different borrowing privilege so elementary students cannot borrow middle school levels books. However, they’ve been kept in the same library so all students can access them. The most interesting thing is, teacher A requested removing the books from middle school area because its contents not appropriate for elementary students. Later, teacher B requested allowed elementary students to check out books because her children loved to read the books in middle school area. Even teachers contradict each other, how can we satisfy everyone and should we compromise? My answer is “When we free them to read, we also free them to reject.” Our job is respecting all reader’s choices, providing help in selecting books if they need, but not limiting their knowledge and prohibiting them from reading the books they loved.Posted : Jan 16, 2017 12:26

tasha mcclendon

ghandi told us "you must be the chnage you want to see in the worl" meaning we choose our happiness or sadness as well as we have control over our actions if a minor was to choose to read an innapropriate book then he/she has power over there actions. yet i do agree with shara we are jumping the material. but also you have to remeber some people hold offices but yet are not worthy of that position or just play a role just shine everyones heart is not in the right direction.Posted : Oct 18, 2016 06:03

Shara

I serve two libraries-a HS library with grades 9-12 and a MS library-grades 6-8. I'm very careful about ordering books for my MS that are "YA". If I'm not sure I look at the reviews. If at least on review says suitable for grades 7 and up then I feel more comfortable ordering it for my MS. The concern I have had for the last couple of years is with our state award books. I push these in both of my buildings. I have seen the MS award book list turn into nearly all YA books. I feel like we are jumping in material from 5th grade to 9th grade and leaving out the MS age. I often wonder if people serving on the MS award book committee really should be on the HS committee? It's really hard to push these books when I know my sixth graders are not mature enough for the some of the material. Each year I feel like I'm just waiting to be challenged with these award books. Anyone else have the same concern?Posted : Oct 17, 2016 10:30

Becky M

I wonder if anyone has ever taken into consideration the Common Core when selecting books for school libraries? If it doesn't align with the Core it makes it difficult to justify using school funds. Just a thought.Posted : Oct 14, 2016 08:43

Anonymous

Hold everything and let's check our facts. The author quotes Shanna Miles like this: "At the urban Atlanta high school where she works, Miles says that many of her students, who range in age from 14 to 21, don’t have access to public libraries because they or their parents don’t have a car or can’t reach public transportation. They might also not have Internet access at home." Maybe Atlanta, Idaho. But not Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta, Georgia has one of the biggest and best mass transit systems in the nation. MARTA doesn't extend all that well to the suburbs, but getting around the city by bus and train is totally no problem. There are 20+ branches of the Atlanta public library to visit, with 9 of them in and around downtown. Bottom line: access to public libraries in Atlanta if a person does not have a car is not the issue.Posted : Sep 30, 2016 10:13

Elaine Fultz

Consider this. Which are we more afraid of? Dealing with an offended parent or administrator or losing a disparaged or suicidal student? Like Shanna Miles mentions above, some kids see only what their limited library offers them. Children and teens who think they are alone in the world suffer. If we don't believe in the power of books to help them, and YES, this means having books with controversial content, we aren't doing our jobs. If the most honest answer to what we are most afraid of is losing our jobs, that's another issue.. Let's be strong for our students and offer them the books they deserve as long as we can.Posted : Sep 30, 2016 06:23

Trav45

Not selecting a book because it is not age appropriate is not censorship, with all its ugly connotations. It's why they pay me: to make informed decisions. Censorship is not buying I am J for a high school (i.e. age-appropriate) library because you don't like the content.Posted : Sep 30, 2016 02:53

Sandra Parks

I borrowed the disclaimer poster below from another librarian who borrowed it from another librarian (and so on ... original sure unknown) and posted it on my website. I also review this with all students, particularly 5th and 6th graders at the beginning of the year. The range in maturity levels and reading interests from 5th-8th grade is vast, but I feel if I do not have relevant materials for my older students, we run the risk of losing them as readers forever. I am not willing to take that risk. A Note about responsible reading In a library that serves students ranging in ages from eleven to fourteen, a wide variety of materials are needed. What is interesting and appropriate for eleven-year-olds may not be interesting and/or appropriate for fourteen-year-olds and vice versa. When students first visit the library each year, Mrs. Parks will tell them that "Libraries are all about choice. If you choose a book that makes you uncomfortable or that would make your parents uncomfortable, please return it and find a book you can completely enjoy." Parents can help students enjoy the library. Ask students what they are reading and talk to them about their choice.Posted : Sep 27, 2016 10:03