2018 School Spending Survey Report

Two Voices, One Stirring Tale: Kathi Appelt and Alison McGhee on "Maybe a Fox"

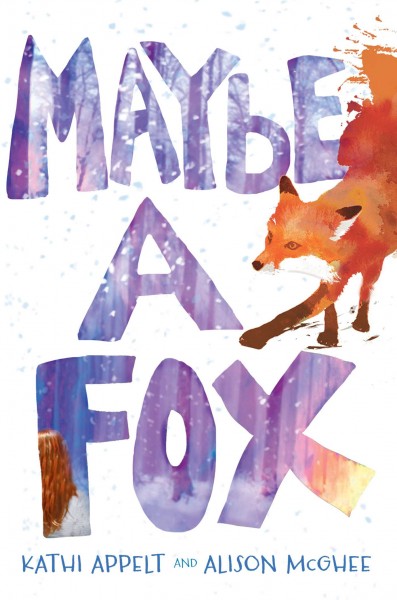

Librarian Kathy Kirchoefer chats with authors Kathi Appelt and Alison McGhee about their unusual collaboration on the middle grade novel Maybe a Fox.

What brought the two of you together to write this book? We met each other when we both joined the faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts at the same time. It was obvious from our first encounter that a wonderful friendship was in the offing. But in the meantime we had to endure the rigors of the residency, and our primary way of doing that was to eat our meals together. We found a small table that was actually in the middle of the cafeteria, but it was flanked by a pair of pillars, making it somewhat secluded. Right there, at that tiny table, we pretty much created our own Vulcan Mind Meld, and in the process we decided that one day we should write a book together. When I first received Maybe a Fox to review, I was intrigued to see how two writers combined their talents to make a cohesive story. Initially, I thought that since the book had two viewpoints, one of 11-year-old Jules and the other of Senna the fox, that Alison was the voice of Jules (I was thinking of "Bink and Gollie" and that Kathi had to have written the animal perspective as she did in The Underneath. Hah! We fooled you! So I wasn’t right in that assumption, was I? Tell us how you pieced the story together. “Pieced” is definitely the operative word here. When we started out, we decided to take on a new challenge, one for each of us. Alison chose the voice of the fox because she had never written in the voice of an animal before. And Kathi wanted to write in a first-person point of view, so she chose Jules. (Obviously that changed to third person somewhere around the 27th draft).

What brought the two of you together to write this book? We met each other when we both joined the faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts at the same time. It was obvious from our first encounter that a wonderful friendship was in the offing. But in the meantime we had to endure the rigors of the residency, and our primary way of doing that was to eat our meals together. We found a small table that was actually in the middle of the cafeteria, but it was flanked by a pair of pillars, making it somewhat secluded. Right there, at that tiny table, we pretty much created our own Vulcan Mind Meld, and in the process we decided that one day we should write a book together. When I first received Maybe a Fox to review, I was intrigued to see how two writers combined their talents to make a cohesive story. Initially, I thought that since the book had two viewpoints, one of 11-year-old Jules and the other of Senna the fox, that Alison was the voice of Jules (I was thinking of "Bink and Gollie" and that Kathi had to have written the animal perspective as she did in The Underneath. Hah! We fooled you! So I wasn’t right in that assumption, was I? Tell us how you pieced the story together. “Pieced” is definitely the operative word here. When we started out, we decided to take on a new challenge, one for each of us. Alison chose the voice of the fox because she had never written in the voice of an animal before. And Kathi wanted to write in a first-person point of view, so she chose Jules. (Obviously that changed to third person somewhere around the 27th draft).

Author Kathi Appelt and a furry friend. Photo credit Igor Kraguljak.

When we first decided to try our hands at this, we basically wrote one chapter at a time, tossing it back and forth to each other, until we had a very raw draft. After that, it took draft after draft after draft to really pull it together. For a long time, we had two stories that were trying to form a single strand, and it took a lot of revising in order to turn it into two strands that made a single story. Jules experiences grief that no 11-year-old should ever have to face, the loss of her sister. Her best friend Sam’s older brother Elk also experiences a similar loss when his best friend Zeke dies while deployed in Afghanistan. Jules is comforted by Elk's understanding of what she is going though. Elk also appears to be suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Explain, if you can, why you made this choice in your story. During the writing of this book, Kathi’s nephew Riley was stationed in Afghanistan and, later, Jordan. He’s in the army, and while we knew/know very little about his experiences there, it nevertheless made the story far more personal. Just through his Facebook posts, it’s obvious that he and his buddies are very tightly knit, and we could imagine that a loss of any of them would have a powerful effect on the others. Through Riley we were able to put a face on Elk. Alison also has students and friends who have been deeply affected by their combat experience, and we funneled our impressions into the character of Elk. And we ourselves have individually experienced long periods of profound stress, which can result in similar reactions. We discuss books at every one of our youth department meetings for librarians. When I introduced this title, the first thing one of my coworkers asked was “Is this a 'death book?' " because I have complained about all the death that takes place in children’s literature, especially for middle grade readers. So, I had to say “yes” to it being a “death book,” but I was quick to point out that it is so much more than that. It’s about grieving, yes, but it is so much more about recovery and hope. Thank you for saying that, because our intention was not to dwell on death, but rather on the possibilities that arise from loss, particularly profound loss. The fundamental question about what happens after we die is one that we all ask. In a way, we have to ask it, and kids seem almost more willing to ponder the possibilities than adults. Physicists have long known that each of us has a kind of energetic force field. Death of our physical body doesn’t necessarily mean that the energy of us ends, too. Why couldn’t that energy be transferred to another living creature, especially if that creature is born at the moment of another’s death? This was what we were pondering when we created the Kennen. And we borrowed that term from the Germanic ken, the best use of which is in the phrase beyond our ken or beyond our knowing. The whole idea of what happens after death is beyond our ken. In addition, we really wanted to show our young readers that the people in our lives who love us, and who we love in return, never really leave us. The Sherman sisters share special rituals and traditions: making "snow families" and throwing wish rocks into the river, as well as their dad’s line “This is Sylvie and Jules’ dad, signing off," which he said every time he looked over their homework. Sylvie and Jules's world holds the great outdoors, close neighbors and friends, and a caring community. Despite the awfulness of Sylvie’s death, that world doesn’t really change, and that gives Jules hope.

Author Alison McGhee. Photo credit Dani Werner.

Yes. The traditions created something solid for our two sisters, and after Sylvie’s death, Jules could see that she needed to recapture that solidness by making new traditions that would both honor Sylvie and also allow her to move on. Have either of you lived in Vermont or in a community like that of Jules? Yes, Alison grew up in a very rural area in upstate New York, not dissimilar to Vermont, and she went to college in Vermont. She now lives there part-time in a tiny shack on a hill, in a clearing surrounded by white pines. Kathi actually grew up in the “wilderness” of very suburban Houston, but she did spend some time in deep East Texas. Upstate New York. East Texas. Lots of tall trees. In Maybe a Fox, there is the very realistic story of what happens to Jules in the wake of losing her sister. Then there's the natural and spiritual world, explored largely through the perspective of Senna, the fox kit who is a kennen. There is beautiful detail in the rock cairns and the Grotto. Tell us a little about the research you did and how you incorporated that information into the book. Alison was the one who brought in the idea of the cairns—she’s always loved the sight of them when out hiking, the comfort and solidarity with hikers who’ve gone before—and she also had some knowledge of rocks; she knew about the names and the categories. We also have a friend, Kerry Bowen White, who is a geologist in Vermont, and she helped us with the technicalities of being a rock hound. Tells us more about catamounts. Are they extinct as Jules and Sam feared? It’s likely that the specific type of catamount that once roamed the northeastern region of North America is extinct. However, just as Sam says over and over again, every single year there’s a sighting. But as with the Ivory Billed Woodpecker, how much of that is magical thinking and how much of it is true is under debate. Grainy photos and indeterminate tracks give us hope. But they aren’t proof. By the end of Maybe a Fox, readers know Jules well. Obviously, writers know their characters even better. What do you think lies in the future for Jules? How will her friendship with Sam withstand adolescence? We believe that their friendship is tried-and-true. We love Super Friend Sam. And we adore sweet Jules. But we also hope that before they settle down, they leave Hobbston for a spell and see the bigger world. Then their woodlands will mean even more to them when, and if, they return. The death of a sibling and PTSD are heavy topics for a children’s book. How did you decide which audience to write for? Why did you pick middle grade audience instead of writing a book for teens? Funny that you would ask, because we originally did write this as a young adult book, but we really wanted to invoke a greater sense of naïveté in our characters, and that called for a younger audience. Writing and/or talking about death to children can be difficult. In this book, the death of a parent, the death of a sibling, and the death of a friend are included. Jules and Sylvie ask one another, “What happens when you die?” as Sylvie continues to grieve for the mother lost to them seven years before. She also struggles with guilt. When Jules finds the Grotto and the wish rocks left there by Sylvie, she finally understands why Sylvie wanted to run faster. Thank you, Kathi and Alison, for sharing that moment with us. Of course. We needed that moment, too. For all of us, we wanted to feel that there really is justice in the world, and that moment felt like a kind of truing had occurred and that the whole world was better because of it. Kathy Kirchoefer is an SLJ reviewer and the youth services coordinator at the Henderson County Public Library in Hendersonville, NC.RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!