2018 School Spending Survey Report

Through a Child's Eyes | A Conversation with Marilyn Nelson

In unrhymed sonnets, the acclaimed poet Marilyn Nelson traces her early years from age four to 14, describing her family's many moves, her growing self-awareness, and her awakening as a poet.

Marilyn Nelson, the acclaimed author of many poetry titles and winner of prestigious awards, wanted to write book on the 1950s. She sent some poems to her editor, and to a longtime mentor, whose advice launched Nelson on a journey to re-examine the decade through the lens of her childhood. The 50 poems in How I Discovered Poetry (Dial, 2014; Gr 6 Up) trace Nelson’s life from age 4 to 14, from 1950 to 1959. The verses, unrhymed sonnets, follow “the speaker” as her military family moves around the United States, and describe the girl’s growing self-awareness, and her awakening as a poet. In your author's note, you write that "each of the poems is built around a 'hole' in the “Speaker's” understanding." Yes. I have a friend, Inge Pedersen, who's a poet and novelist in Denmark. She published a memoir of her girlhood in the 1930s, when Denmark was occupied by the Nazis. She told me that each of [her] stories [evidences] a gap in a child's understanding of the world around her. I address the same sort of ‘gaps’ in these poems.

Marilyn Nelson, the acclaimed author of many poetry titles and winner of prestigious awards, wanted to write book on the 1950s. She sent some poems to her editor, and to a longtime mentor, whose advice launched Nelson on a journey to re-examine the decade through the lens of her childhood. The 50 poems in How I Discovered Poetry (Dial, 2014; Gr 6 Up) trace Nelson’s life from age 4 to 14, from 1950 to 1959. The verses, unrhymed sonnets, follow “the speaker” as her military family moves around the United States, and describe the girl’s growing self-awareness, and her awakening as a poet. In your author's note, you write that "each of the poems is built around a 'hole' in the “Speaker's” understanding." Yes. I have a friend, Inge Pedersen, who's a poet and novelist in Denmark. She published a memoir of her girlhood in the 1930s, when Denmark was occupied by the Nazis. She told me that each of [her] stories [evidences] a gap in a child's understanding of the world around her. I address the same sort of ‘gaps’ in these poems.

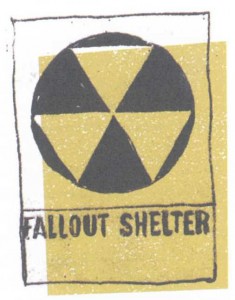

Interior image from "How I Discovered Poetry" (Nelson) Dial, © Hadley Hooper

Your poems include references to historic events—for instance, a hydrogen bomb—in a way that a child might describe them, or understand them. A hydrogen bomb becomes "hide drajen bomb." Yes, for that poem I was trying to spell it the way a child would. You mention teachers who encouraged you, two in particular: Miss Jackson and Mrs. Gray. I was in Miss Jackson's homeroom and her English class for about half of a semester. Miss Jackson noticed I was practicing piano on my desk, and she had me placed in a music class. She also introduced me to African American poetry. Mrs. Gray, my sixth grade teacher, told us about poetic form, a bit. I remember learning the different metrical feet in her class. She said the iambic foot, which is duh-DUM, is to walk. Trochaic, which is DA-dum, is running. Tell us about the experience, reading that poem in class, which you capture in "How I Discovered Poetry." Another teacher, Mrs. Purdy, pressures you to read a poem to your classmates, a poem that contains racist phrases and stereotypes; you describe the silent walk to the bus with your white classmates that followed. I wrote that poem, "How I Discovered Poetry," years ago. When I decided to start working on this book, it seemed like that was a central experience. It should be the heart of this book. What the poem is trying to express is that first awareness of the power of the word. The power of the word is creative but it also can be really destructive. That's why all of us were silent after that. I believe all of my classmates saw that teacher humiliate me in a really cruel way—publicly humiliate me for no reason other than racism.

Interior image from "How I Discovered Poetry" (Nelson) Dial © Hadley Hooper

One of the most profound moments occurs at the end of the book, when young Marilyn feels a calling as a poet. Did that revelation come to you at about that age, 13? Oh yes. That prediction that Mrs. Gray made on the last day of class, when she said I would be a poet when I grew up, that really did happen. The earliest poems I wrote, which my mother kept, must have been from about sixth grade. I know that at that time I was reading anthologies. We had a little library that traveled with us when we were transferred from here to there. Most were my father's from college: a book of endocrinology, with photos inside the human body; an anthropology book, Our Primitive Contemporaries, which I still own and love; and a poetry collection. I read it and reread it; it was my bible for a couple years. I decided that when I grew up I wanted to have a poem in a book like that. From your poems, it seems as though you had a more inclusive world view than your mother. Was that something you talked about with her? It was something I kept to myself, but something I reflected upon often. My mother grew up in an all-black town, Boley, OK. She had lived happily in a segregated world for all of her life, until she joined my father on the road. She went to a black college, Kentucky State University, where her father was president. Until meeting my father, her world was completely a black world. My father's was, too, but he'd grown up in a city, so he knew of the existence of white people. My mother was very race-proud. Something I remember about wanting everyone to be in my family, was driving through Kansas, through miles and miles of nothing. This was before superhighways; this was Route 66. I wanted to write postcards to people, telling them God loves them: "I love you. [Signed] God." That's all I could think about, could we stop and get a name from a mailbox or telephone directory? In a way it's that plea in the book’s final poem, “Thirteen-Year-Old American Negro Girl”: "Give me a message I can give the world." Listen to Marilyn Nelson reveal the story behind How I Discovered Poetry, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

Listen to Marilyn Nelson reveal the story behind How I Discovered Poetry, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!