2018 School Spending Survey Report

Then and Now: Wendy Mills on 9/11 and “All We Have Left”

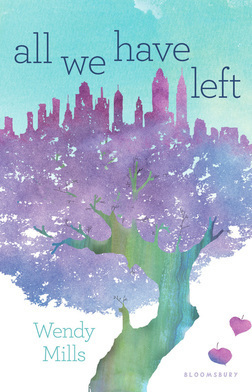

SLJ chats with Wendy Mills, who explores September 11 through the perspectives of a present-day white teen whose brother died on that fateful day and a young Muslim American woman who is trapped in the Twin Towers on 9/11.

It’s hard to believe that 15 years have passed since two airplanes flew into the Twin Towers in New York City and thousands of people perished. In All We Have Left (Bloomsbury, Aug. 9, 2016), Wendy Mills explores the then and now of 9/11 through the perspectives of two teens—one a present-day white girl whose brother died on that fateful day and the other a Muslim American teen experiencing the horrible tragedy on September 11, 2001. What inspired you to write this narrative from these specific points of view? I knew I was interested in the juxtaposition of a teenage girl inside the Twin Towers on September 11 and a girl living with the aftermath 15 years later, but I wasn’t sure how I wanted to tell the story. It was only when I ran across an article in the New York Times describing how the Muslim staff members of a restaurant in the North Tower prayed daily on cardboard prayer mats in the stairwell that I was truly reminded that people of diverse faiths died together that day. That’s when I knew I wanted a Muslim main character, to more fully explore the ramifications of 9/11. At that point, the story just clicked. Jesse has grown up with a father spewing hatred for the Muslims he blames for killing his son in the Twin Towers; Alia is a Muslim teen who, along with Jesse’s brother, fights to survive inside those towers as the planes hit. What kind of research did you do to get the details of that day so right? Researching this book was emotionally wrenching. As I pored over books and articles about 9/11 and watched countless interviews and documentaries, my heart felt as if it were breaking. The amount of information was almost overwhelming, but for the purposes of research, I was fortunate to have so many first-person accounts put on paper immediately following 9/11, before memories were blurred by the passage of time. I read so many stories showing the bravery of ordinary people that day—not to mention the bright heroism of the first responders—that I wanted to include each and every one. I remember standing in the 9/11 Memorial Museum, listening to the last messages from people trapped inside the towers, and I completely broke down. It’s horrifying to imagine what those people were going through that day. It’s desperately sad to think we might one day forget. My intent was not to exploit their horror but rather to illuminate the goodness and courage of those ordinary people fighting for their lives inside the towers—to make sure we never forget this is what it is to be human. What kind of research did you do to get into the heads of these two very different teens? I worried about writing Alia’s point of view, because I knew it would be difficult as a non-Muslim to write a realistic Muslim character. However, I felt strongly that this was a perspective I needed to show. I had read the Koran, as well as many books and articles about Islam, but it was only when I began meeting every week with a lovely group of people that I really started to understand what it was like to live as a Muslim: fasting through the long summer hours of Ramadan, without a sip of water or even a breath mint to soften your dry mouth; making up for prayers you missed during the school day; shopping for that perfect scarf, and the variety of different ways you could wear it; finding the best halal pizza joint. I witnessed the unabashed joy and peace of performing daily prayers and listened to the soft murmur of voices chanting in unison, punctuated by the crackling of old knee joints. I loved learning about the details that were unique to a Muslim character, but I also thought it was important to highlight the fact that Alia is an American teen and her problems and issues are the same as those of any other American teen.

It’s hard to believe that 15 years have passed since two airplanes flew into the Twin Towers in New York City and thousands of people perished. In All We Have Left (Bloomsbury, Aug. 9, 2016), Wendy Mills explores the then and now of 9/11 through the perspectives of two teens—one a present-day white girl whose brother died on that fateful day and the other a Muslim American teen experiencing the horrible tragedy on September 11, 2001. What inspired you to write this narrative from these specific points of view? I knew I was interested in the juxtaposition of a teenage girl inside the Twin Towers on September 11 and a girl living with the aftermath 15 years later, but I wasn’t sure how I wanted to tell the story. It was only when I ran across an article in the New York Times describing how the Muslim staff members of a restaurant in the North Tower prayed daily on cardboard prayer mats in the stairwell that I was truly reminded that people of diverse faiths died together that day. That’s when I knew I wanted a Muslim main character, to more fully explore the ramifications of 9/11. At that point, the story just clicked. Jesse has grown up with a father spewing hatred for the Muslims he blames for killing his son in the Twin Towers; Alia is a Muslim teen who, along with Jesse’s brother, fights to survive inside those towers as the planes hit. What kind of research did you do to get the details of that day so right? Researching this book was emotionally wrenching. As I pored over books and articles about 9/11 and watched countless interviews and documentaries, my heart felt as if it were breaking. The amount of information was almost overwhelming, but for the purposes of research, I was fortunate to have so many first-person accounts put on paper immediately following 9/11, before memories were blurred by the passage of time. I read so many stories showing the bravery of ordinary people that day—not to mention the bright heroism of the first responders—that I wanted to include each and every one. I remember standing in the 9/11 Memorial Museum, listening to the last messages from people trapped inside the towers, and I completely broke down. It’s horrifying to imagine what those people were going through that day. It’s desperately sad to think we might one day forget. My intent was not to exploit their horror but rather to illuminate the goodness and courage of those ordinary people fighting for their lives inside the towers—to make sure we never forget this is what it is to be human. What kind of research did you do to get into the heads of these two very different teens? I worried about writing Alia’s point of view, because I knew it would be difficult as a non-Muslim to write a realistic Muslim character. However, I felt strongly that this was a perspective I needed to show. I had read the Koran, as well as many books and articles about Islam, but it was only when I began meeting every week with a lovely group of people that I really started to understand what it was like to live as a Muslim: fasting through the long summer hours of Ramadan, without a sip of water or even a breath mint to soften your dry mouth; making up for prayers you missed during the school day; shopping for that perfect scarf, and the variety of different ways you could wear it; finding the best halal pizza joint. I witnessed the unabashed joy and peace of performing daily prayers and listened to the soft murmur of voices chanting in unison, punctuated by the crackling of old knee joints. I loved learning about the details that were unique to a Muslim character, but I also thought it was important to highlight the fact that Alia is an American teen and her problems and issues are the same as those of any other American teen.  How did you write and plot the two narratives? Did you write Jesse’s chapters first and then Alia’s? As I am writing, my stories often have an almost tangible weight and feel in my mind. In the case of All We Have Left, my mental image of the story was of many rainbow-colored threads. When the two girls’ stories interlocked and complemented each other, the threads were braided into a beautiful pattern; when they did not, the threads were snarled and tangled. As I had never attempted to write a book with alternating viewpoints, the process itself was trial and error. At the beginning, I wrote their two viewpoints separately and then fit them together. As the two stories grew more closely enmeshed, it became necessary to write them “in order.” The real struggle began when we were going through the editing process. There was a major plot change that my excellent editor and I agreed was necessary, but it required me to rewrite a good bit of Alia’s sections and, to a smaller extent, Jesse’s. Weaving their stories back together again was very challenging. Since 9/11, there’s been so much rhetoric against the Muslim community. Why did you think it was important to include that in this novel? A Muslim friend told me that he felt as if has had to apologize every day for the past 15 years for something he didn’t do. Our Muslim American neighbors have borne the brunt of the anger and fear of our country over the past years, and in some ways, it felt impossible to write this story without including a Muslim perspective. It is easy to dehumanize a group of people when you don’t know them; it is harder when you realize you have more in common than differences that separate you. When I began this story, I knew the message was important, but it makes me sad to think how much more important it has become. Which character was the most difficult to write? I identified strongly with both of my characters in certain ways; like Jesse, I remember internalizing my parents’ beliefs without asking questions and feeling such a desperate need to fit in that I did things I shouldn’t have. In Alia’s story, her resentment toward her parents for not letting her do something she wants do was very familiar as well. Jesse’s sections were hard to write because in the beginning she was making such bad decisions and acting out in ways that made me uncomfortable. But I thought it was important to show how she got to that dark, racist place—because it is a place that many people inhabit—and then show how she was able to grow so beautifully as a person. In the end, Alia’s character was the hardest to write—not because she was Muslim but because she was in the towers. What she experienced—what all the people in the towers experienced–was so devastating. It was very difficult to write. What do you see your protagonists doing on the 20th anniversary of 9/11? Twenty years after 9/11, we will have a generation of children coming of age never knowing what the world was like before [that day]. So many things have happened as a direct result of that terrible [event], and these children—these future teachers, citizens, leaders—will have to navigate our troubled world with the help of the skills and the gifts of knowledge that we as parents and teachers give them. On the 20th anniversary of 9/11, my characters will be living their lives like the rest of us, and I hope fervently that the world is a saner, kinder place. Are you working on anything right now? I am always looking for stories that illustrate something about ourselves and our society. At the moment, I am working on a story about refugees. There are more refugees in the world today than at any other time on record, and more than half of them are children. There is an important story here, and I am determined to tell it.

How did you write and plot the two narratives? Did you write Jesse’s chapters first and then Alia’s? As I am writing, my stories often have an almost tangible weight and feel in my mind. In the case of All We Have Left, my mental image of the story was of many rainbow-colored threads. When the two girls’ stories interlocked and complemented each other, the threads were braided into a beautiful pattern; when they did not, the threads were snarled and tangled. As I had never attempted to write a book with alternating viewpoints, the process itself was trial and error. At the beginning, I wrote their two viewpoints separately and then fit them together. As the two stories grew more closely enmeshed, it became necessary to write them “in order.” The real struggle began when we were going through the editing process. There was a major plot change that my excellent editor and I agreed was necessary, but it required me to rewrite a good bit of Alia’s sections and, to a smaller extent, Jesse’s. Weaving their stories back together again was very challenging. Since 9/11, there’s been so much rhetoric against the Muslim community. Why did you think it was important to include that in this novel? A Muslim friend told me that he felt as if has had to apologize every day for the past 15 years for something he didn’t do. Our Muslim American neighbors have borne the brunt of the anger and fear of our country over the past years, and in some ways, it felt impossible to write this story without including a Muslim perspective. It is easy to dehumanize a group of people when you don’t know them; it is harder when you realize you have more in common than differences that separate you. When I began this story, I knew the message was important, but it makes me sad to think how much more important it has become. Which character was the most difficult to write? I identified strongly with both of my characters in certain ways; like Jesse, I remember internalizing my parents’ beliefs without asking questions and feeling such a desperate need to fit in that I did things I shouldn’t have. In Alia’s story, her resentment toward her parents for not letting her do something she wants do was very familiar as well. Jesse’s sections were hard to write because in the beginning she was making such bad decisions and acting out in ways that made me uncomfortable. But I thought it was important to show how she got to that dark, racist place—because it is a place that many people inhabit—and then show how she was able to grow so beautifully as a person. In the end, Alia’s character was the hardest to write—not because she was Muslim but because she was in the towers. What she experienced—what all the people in the towers experienced–was so devastating. It was very difficult to write. What do you see your protagonists doing on the 20th anniversary of 9/11? Twenty years after 9/11, we will have a generation of children coming of age never knowing what the world was like before [that day]. So many things have happened as a direct result of that terrible [event], and these children—these future teachers, citizens, leaders—will have to navigate our troubled world with the help of the skills and the gifts of knowledge that we as parents and teachers give them. On the 20th anniversary of 9/11, my characters will be living their lives like the rest of us, and I hope fervently that the world is a saner, kinder place. Are you working on anything right now? I am always looking for stories that illustrate something about ourselves and our society. At the moment, I am working on a story about refugees. There are more refugees in the world today than at any other time on record, and more than half of them are children. There is an important story here, and I am determined to tell it. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!