The Power of Story by Angela Cervantes

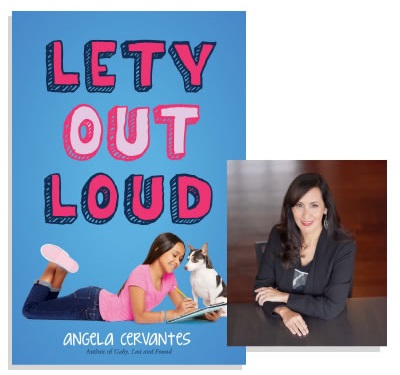

Lety is a story about Lety Muñoz, an English Language Learner (ELL) and immigrant, who volunteers at an animal shelter and becomes a shelter hero.

My Mexican grandparents were the first storytellers in my life. They told their stories in Spanish, English and a mix of both—whichever language they preferred at that moment. My favorite stories were the ones my abuela told while holding my hand as we walked to the store. During those walks, she told me about La Llorona, the crying woman who drags children to the river, and the bone-chilling tale of El Cucuy, a boogieman that hides in the basement. Yikes, scary stuff!

My Mexican grandparents were the first storytellers in my life. They told their stories in Spanish, English and a mix of both—whichever language they preferred at that moment. My favorite stories were the ones my abuela told while holding my hand as we walked to the store. During those walks, she told me about La Llorona, the crying woman who drags children to the river, and the bone-chilling tale of El Cucuy, a boogieman that hides in the basement. Yikes, scary stuff!

My abuelo was a quiet man who loved to garden and sew as much as he loved to tell us a good story. Whenever I’d hold my abuelo’s hands, he’d joke about how he would steal my fingers to replace the two fingers he’d lost. When my siblings or I asked about how he lost his fingers, he’d claim that the first one had been pecked off by a chicken, annoyed at my abuelo for chasing it. He said the second finger was lost when a spider, angry that my abuelo had destroyed its web, bit him on the finger. The next day his finger turned blue and shriveled off. The truth, which I would learn later, was that my abuelo had lost his two fingers in an accident while he worked on the railroads. I cringe just thinking of my grandpa in that sort of pain. Still, he never spoke about it in painful terms. Instead, he created outlandish stories that made his grandchildren laugh.

I thought of my Mexican grandparents a lot when I set out to write my latest novel, Lety Out Loud. Lety is a story about Lety Muñoz, an English Language Learner (ELL) and immigrant, who volunteers at an animal shelter and becomes a shelter hero. I drew upon my abuelos’ brave lives as immigrants coming to this country and the ways in which they wrestled with language, culture, and discrimination to create a better life.

Growing up, I didn’t see any stories about girls with Mexican-American heritage like me. Nor did I ever find any books about children who were ELLs like my grandparents. Some people viewed their lack of English as a deficiency, but I always thought they were geniuses.

I saw their ability to take on a new language and culture, and to live in a new country as courageous. I believed then, as I do now, that children deserve mirror books that give their lives and experiences dignity. After all, not being fluent in English doesn’t mean these children don’t have stories to tell. It doesn’t mean they don’t have things to teach us. It simply means English isn’t their first language.

While I was writing Lety Out Loud, a friend of mine posted on Facebook that his wife and daughter had been verbally assaulted at a store while they were speaking Spanish to each other. A complete stranger yelled at them, “Speak English or go back to Mexico!” (Nevermind that they are actually from Colombia). This incident struck me hard, like many of the other viral videos of strangers verbally attacking people for speaking languages other than English. I wondered how I’d react if I was ever in the same situation? I feel very confident that I could handle it, but what about a child? How would a student like one of the many ELLs I’ve met at school visits respond? How would my main character, Lety, respond?

Would it give her nightmares? Would it make her resentful? Would it motivate her? Should I, as a writer, be honest with children about how hateful some people can be? Should I shield them from this? Or could I guide them with stories in the same way my abuelos provided stories for me while holding my hands?

As I started drafting a tough scene when Lety and her friends are bullied with a cry of, “Speak English or go back to Mexico!” I stopped after writing one sentence. There was already so much negativity going on in the world and it pained me to have to tell this story. I stopped writing the novel. After two weeks of avoiding it, Lety’s voice spoke to me and told me that she needed me to finish the scene. Children like her should have a voice. This was not the time to be quiet. Then another voice spoke up. This time, it was the words of author Kate DiCamillo, who in a letter to fellow author Matt de la Peña reflected on the work of E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. She wrote, “And in loving the world, he told the truth about it — its sorrow, its heartbreak, its devastating beauty. He trusted his readers enough to tell them the truth, and with that truth came comfort and a feeling that we were not alone.”

Finally, I sat down and wrote the scene that had stopped me cold. I finished the novel as if I were holding my abuelos’ hands on one of our long walks to the store. Because of them, I enjoy the luxury of sitting in my comfy writing room and inventing stories all day. It is luxury. It is also a responsibility—a beautiful responsibility—to write stories that reflect the diversity of my community, stories that are windows that build empathy, and stories that tell the truth—all the while holding your hand. This, to me, is the power of story.

Angela Cervantes is a poet, storyteller, and animal lover. Her poetry and short stories have appeared in various publications, and she has written the novels Gaby, Lost and Found and Allie, First at Last. Her latest, Lety Out Loud, is available now. When Angela is not writing, she enjoys hanging out with her husband in Kansas and eating fish tacos every chance she gets. Keep up with Angela at angelacervantes.com.

This article is part of the Scholastic Power of Story series. Scholastic’s Power of Story highlights diverse books for all readers. Find out more and download the catalog at Scholastic.com/PowerofStory. Visit School Library Journal to discover new Power of Story articles from guest authors, including Sayantani DasGupta, Nafiza Azad, book giveaways and more.

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!