Six Manga About People with Disabilities

In these works, characters with disabilities are presented as well-rounded, complex personalities.

|

From: I Hear the Sunspot (Fumino) |

In the world of American graphic novels, memoirs such as Raina Telgemeier’s Guts (Graphix, 2019) and Cece Bell’s El Deafo (Abrams, 2014) have presented firsthand accounts of the lives of people with disabilities. In fiction, Chris Grine’s Secrets of Camp Whatever (Oni Press, 2021) and Alina Chau’s Marshmallow and Jordan (First Second, 2021) both feature lead characters with disabilities. Yet people with disabilities are largely absent from the most popular category of graphic novels in America: manga.

In the world of American graphic novels, memoirs such as Raina Telgemeier’s Guts (Graphix, 2019) and Cece Bell’s El Deafo (Abrams, 2014) have presented firsthand accounts of the lives of people with disabilities. In fiction, Chris Grine’s Secrets of Camp Whatever (Oni Press, 2021) and Alina Chau’s Marshmallow and Jordan (First Second, 2021) both feature lead characters with disabilities. Yet people with disabilities are largely absent from the most popular category of graphic novels in America: manga.

There are currently only a handful of manga in English that feature well-developed characters with disabilities, and Shuzo Oshimi’s Shino Can’t Say Her Name may be the first translated manga by a creator with the disability depicted in the story. However, the popularity of the series “A Silent Voice” and “Komi Can’t Communicate” suggests that these stories can strike a chord with American readers.

The disability rights movement in Japan began in the 1960s, and the first comprehensive disability legislation was passed in 1993. After Japan ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2007, the government formed a committee of people with disabilities to bring the country’s laws into compliance; that work was completed in 2014. As a result, Japan has made great strides in recent years in affirming the rights of people with disabilities and removing physical and social barriers. The more recent titles reflect this, and in Reframing Disability in Manga (University of Hawai’i Press, 2020), scholar Yoshiko Okuyama states that Japanese publishers are now including more characters with disabilities and have specific guidelines for representing disability.

My goal with this column is to present manga in which characters with disabilities are presented as well-rounded, complex personalities, whether or not they are the main characters. These suggested titles are a short list, but one that hopefully will grow in the future.

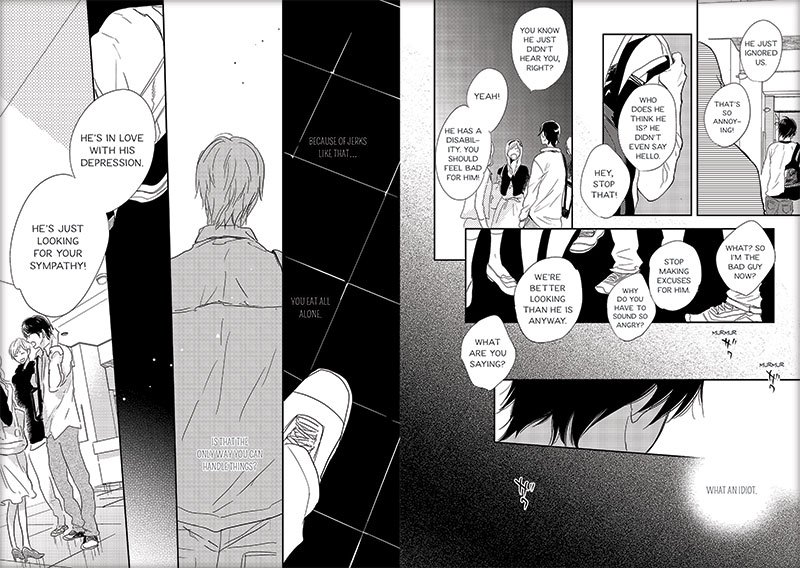

“I Hear the Sunspot,” by Yuki Fumino (One Peace Books, 2017)

Gr 8 Up—This is a story of friendship deepening into love between two college students: Kohei, who is hard of hearing, and Taichi, who is not. Taichi is perpetually broke, and he and Kohei become friendly when Kohei shares his lunch with him. Later, the two make a deal: Taichi will take notes for Kohei in class and Kohei will bring Taichi lunch every day. Kohei is handsome, but some of the girls who like him have patronizing attitudes, pitying him and making assumptions (such as that he uses sign language, which is not universal among people with hearing disabilities). Fumino does a good job of depicting Kohei’s frustration when he misses part of a conversation and is waved away with “never mind,” rather than being included. Although it’s yaoi, this story is very light on the romance because, as Fumino confesses in an afterword, she didn’t realize it was supposed to be a romance until late in the process. This graphic novel stands well on its own, but there is also a sequel, I Hear the Sunspot: Theory of Happiness, as well as a short series, “I Hear the Sunspot: Limit.”

“Komi Can’t Communicate,” by Tomohito Oda (Viz, 2019-2021)

Gr 8 Up—Komi is stunningly beautiful, so much so that her classmates see her as an ice queen. But her reserve doesn’t come from haughtiness or snobbery: She experiences severe anxiety whenever she tries to speak. Not only that, she mistakes their exaggerated respect for hostility and thinks no one likes her. The upshot is that she has no friends. In a frenzied conversation carried out with chalk on a blackboard, she explains her anxiety to her classmate, the awkward but good-hearted Tadano, and he resolves to help her make 100 friends. The story is told in short episodes, each one a fragment of a school day, and while it’s mostly told from Tadano’s point of view, it sometimes switches to Komi or another student. Several of the other students also have different degrees of social anxiety, and once they realize the reason Komi seldom speaks, they accept her. This is a shonen romantic comedy where everyone is over the top, and the other students’ reactions to Komi are somewhat exaggerated. Despite her anxiety, Komi advocates for herself, declaring “I choose who to be friends with” and pushing the others into situations that are difficult even for them. The manga has been adapted into an anime, which is also available in English. (16 volumes, ongoing)

“Real,” by Takehiko Inoue (Viz, 2008-2021)

Gr 11 Up—Inoue’s wheelchair basketball saga is both brutal and moving. He starts with 17-year-old Nomiya dropping out of school, leaving a final farewell by defecating on the front step. An avid basketball player, Nomiya quit the team and went into a downward spiral after he crashed his motorcycle in an accident that left him unscathed, but permanently paralyzed Natsumi, the girl who was riding with him. Filled with guilt, he visits Natsumi in the hospital and wonders what she is like; he can’t even remember hearing her voice. One day while they are out together, he sees an intense young man in a wheelchair playing basketball. This is Togawa, a driven athlete who lost a leg to bone cancer. Their shared love of the game brings the two together in an edgy friendship. The third player, Takahashi, was the captain of Nomiya’s team and bullied Nomiya’s friends after he dropped out. Takahashi becomes a paraplegic after a traffic accident. All three characters are strong-willed but marginalized by society: Nomiya because he simply doesn’t fit in with the rest of his schoolmates, and the other two because of their disabilities. Inoue’s other basketball manga, “Slam Dunk” (Viz, 2008-2013) popularized the sport in Japan, and “Real” is very much of a sports manga as well; but it’s also a story of three young men growing up and learning to navigate a society that is often hostile to them. Unfortunately, the early volumes are out of print, but the entire series is available digitally, and volume 15 was published, after a long hiatus, in December 2021. (15 volumes, ongoing)

“Shino Can’t Say Her Name,” by Shuzo Oshimi (Denpa Books, 2021)

Gr 9 Up—High school gets off to a rough start for Shino, who has trouble speaking in front of other people and particular difficulty saying her own name. It starts on the very first day, when everyone in the class has to stand up and introduce themselves. When it’s Shino’s turn, she struggles and stutters, and the class mocks her. Being unable to carry on a conversation or answer a question in class isolates Shino from her classmates; her teacher is sympathetic, but not particularly helpful. Things start turning around when she makes friends with her prickly yet caring classmate Kayo. Kayo loves playing the guitar but can’t sing at all, while Shino can sing more fluently than she speaks. When Kayo wants to perform in public, though, that’s too much for Shino, and she breaks off the friendship. There’s also some drama with the boy who first mocked her, who ultimately apologizes to Shino but still alienates her. The story ends on a dramatic note, with Shino expressing her frustration and her pain at being mocked by others, but also acknowledging that her speech disability is simply part of who she is. In a short coda, we see Shino as an adult, still struggling to say her name, but she now has the support of her daughter. Oshimi ends with a note about his own struggles with speaking to others. (One volume)

“A Sign of Affection,” by Suu Morishita (Kodansha Comics, 2020-2021)

Gr 11 Up—This sweet romance is told from the point of view of the Deaf character, and it also places heavy emphasis on communicating with sign language. The main character, Yuki, is a college student who still lives with her family but also has a good friend at school, Rin. After another student, Itsuomi, rescues her from an awkward situation, Yuki is intrigued, and since Rin already knows him and has a crush on his boss, the romance gets off to a smooth start. Itsuomi, a world traveler who speaks three languages, asks Yuki to teach him sign language, which gives the couple plenty of excuses to converse. While Itsuomi does have the cool, stand-offish attitude of many male manga characters, the people around him comment on how gentle his voice is when he talks to Yuki. Nonetheless, the others worry that he’s not as much in love as Yuki is. Another complication is Yuki’s childhood friend Oushi, who uses sign language and has an overprotective attitude toward her; he is suspicious of Itsuomi and possibly jealous as well. The creators of this manga started out with the concept of incorporating sign language into their story, and they have a sign language consultant who ensures that the signs they portray are accurate. (Four volumes, ongoing)

“A Silent Voice” by Yoshitoki O–ima (Kodansha Comics, 2013)

Gr 8 Up—Although this manga has been hailed by critics and was nominated for an Eisner Award, it is somewhat problematic. The story revolves around the lead character, Shoya, who bullies a Deaf girl, Shoko, in sixth grade, and later, as a high school senior, tries to make amends. As a kid, Shoya Ishida is, in his own words, “at war with boredom,” and he fights back with increasingly edgy and dangerous stunts. When Shoko transfers to his school, Shoya is fascinated with her and torments her, with his classmates eagerly following his lead. Then the bullying goes too far, and his classmates turn on him and isolate him. The story skips forward to Shoko’s senior year of high school. Guilty about what he did to Shoko and how it alienated him from everyone, Shoya decides to die by suicide; but first he wants to apologize to Shoko. When they meet, his feelings change. He decides to keep living and try to restore to her the friends and good times that he took away in sixth grade. He learns sign language to communicate with her and brings their old circle back one classmate at a time. The story is told almost entirely from Shoya’s point of view, and it’s actually unusual in that it gets inside the head of a bully. In fact, although this is never stated directly, his constant pushing of boundaries hints that he may be neuroatypical himself. Shoko, on the other hand, is a rather flat character with a tendency to smile and apologize, but she occasionally asserts herself. Shoya’s guilt and his desire to “rescue” Shoko are definitely problematic, but this manga can provide some useful starting points for discussion, especially as the large cast offers a wide spectrum of personalities who interact with Shoko and Shoya in different ways as they mature. The manga was adapted into an anime film, which is available in English. (Seven volumes, complete)

Brigid Alverson edits the blog “Good Comics for Kids” (slj.com/goodcomics).

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!