Graphic Novels, Manga Explode in Popularity Among Students | SLJ Survey

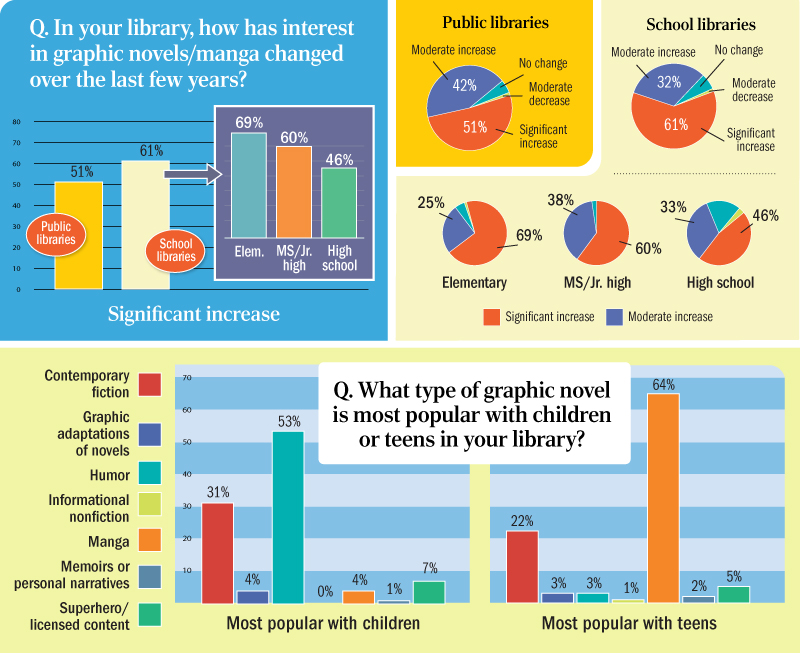

If graphic novels are flying off the shelves at your library, that reflects a remarkable trend: The format’s popularity has shot up at over 90 percent of school libraries in the last few years, according to a new SLJ survey.

|

Illustration by Michael Byers |

|

METHODOLOGY: A survey invite was emailed to a random sample of school librarians and youth public librarians in May 2023. The survey closed with 861 U.S. responses (531 schools and 330 public libraries). The data was collected, tabulated, and analyzed by SLJ Research. This survey was sponsored by Kodansha. |

If graphic novels are flying off the shelves at your library, that reflects a remarkable trend: In the last few years, the format’s popularity has shot up at over 90 percent of school libraries, according to a new SLJ survey, with the biggest jump in elementary schools. Students are clamoring for humor and contemporary fiction, in particular, and manga is exploding in popularity. Manga works now comprise 43 percent of high school graphic novel purchases, according to librarians who responded to SLJ’s 2023 Graphic Novels Survey.

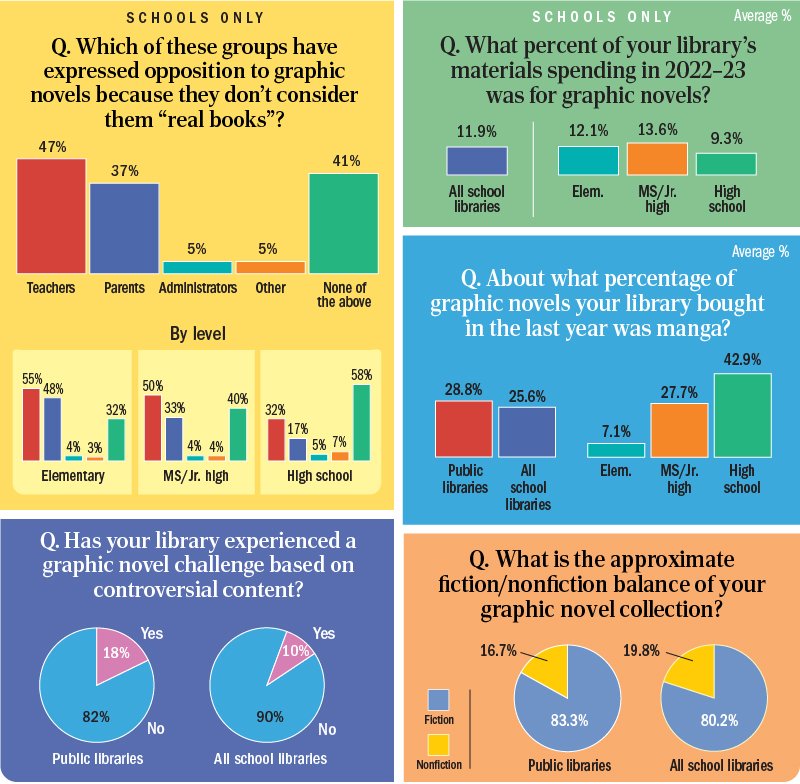

Educators are leveraging the enthusiasm to excite students about books, particularly striving readers and English language learners, despite objection by adults: 59 percent of school librarians reported opposition to graphic novels from teachers, parents, and others who didn’t consider them “real books.” While there are censorship attempts—18 percent of public libraries and 10 percent of schools have experienced challenges to graphic-format works—students’ fervor is only building.

“Book challenges have had no effect on our graphic novel collection,” said an elementary school librarian in North Carolina, who added that the collection “continues to grow every year. There is huge demand from our students.”

All respondents—531 school librarians and 330 public librarians—had graphic novel collections available for students. Ninety-one percent shelve them in their own section so they’re easier to find.

At 40 percent of school libraries and 26 percent of public ones, graphic-novel readers only read in this format, respondents said. This led 90 percent of public librarians and 83 percent of school librarians to suggest them to students who struggle with reading. In particular, 57 percent of public librarians and 69 percent of school librarians recommend them to English language learners.

“For many children, graphic novels start their love of reading, because words are broken down into smaller spaces with lots of pictures,” said a Vermont public librarian.

“Students are generally shocked that the high school teachers allow them to read graphic novels as part of their independent reading,” reported a Texas high school librarian. “I think it makes them want to read them more, since they were once not allowed to.”

Graphic adaptations of novels and humor books are most common in school libraries overall, while manga, superhero stories, and graphic memoirs are more prevalent in middle and high school libraries. Younger kids prefer humor (53 percent), while more teens want manga (64 percent).

Kids devour graphic novel series, which are strongly preferred in 36 percent of public libraries and 42 percent of school libraries (51 percent of elementary schools) over one-off titles. What is most popular? “Dog Man,” “Baby-Sitters Club,” “Amulet,” “Big Nate,” and “Wings of Fire,” as well as Raina Telgemeier’s books Smile and Drama.

Top manga series: “Naruto,” “My Hero Academia,” “Demon Slayer,” “Pokémon,” and “Dragon Ball Z.” How are librarians handling the growing demand? Among public librarians, 84 percent offer programming: a graphic novel or manga club, a “make your own graphic novel” project, or a “con” or cosplay activity. At schools, 26 percent said teachers use graphic novels in curricula—including Maus, Persepolis, the “March” series, To Kill a Mockingbird, When Stars are Scattered, The Crossover, They Called Us Enemy, and Hey, Kiddo.

Numbers confirm the sea change in U.S. students’ enthusiasm for manga. Among public and school libraries, 15 percent of respondents said that over half of graphic novels bought in the last year were manga. The balance of manga titles in schools increases with age; the average is 7 percent in elementary schools, 28 percent in middle schools, and up to 43 percent in high schools.

Objection to the graphic novel format was high in elementary schools, where 68 percent faced opposition from people claiming they aren’t “real books”; 55 percent said complaints came from teachers, and 48 percent from parents.

Julianne Ninteman, a middle school librarian in Minnesota, said adults “put kids down for reading them, or even forbid them to read them, or [teachers] won’t give them reading credit in class if they have a graphic novel.”

“We have had to be much more cautious about graphic novels in recent years,” said a middle school librarian from Maine. “Some manga that used to be no big deal, we now can’t have at all.... We’ve also had people upset just by the word ‘graphic,’ not understanding that this means ‘images,’ and not ‘x-rated.’”

While 74 percent of public libraries and 59 percent of school libraries haven’t taken steps to avoid graphic novel challenges, 19 percent of schools have stopped buying titles that might be controversial, and 11 percent of high schools have removed titles such as Fun Home and The Handmaid’s Tale.

“I am very, very careful,” said Nicole Gasparini, a middle school librarian in Illinois. She reads reviews, blogs, and websites dedicated to graphic novels. “I check cover art and have used my trusty Sharpie to black out anything that looks like nudity.”

A public librarian in Wisconsin said, “I use the ‘frequently challenged titles’ list as a ‘suggested purchases’ list.… My copy of Gender Queer was recently returned with a note in it saying, ‘Thank you for having this book on your shelves.’”

For a Louisiana school librarian, the potential for challenges “has led me to retire at the end of this school year.”

What’s being challenged? Gender Queer, Flamer, “Heartstopper,” Fun Home, Blankets, Maus, and Drama, among others.

Gender Queer was mentioned by multiple respondents. In most cases, it was retained or moved from YA to adult sections. In a few cases, it was removed.

A Massachusetts high school librarian said Gender Queer and Let’s Talk About It were both retained after challenges, but “community members keep using pages from these and other graphic novels to call me, my principal, and the school committee members who voted to keep the books in the library horrible things online, on the radio, and in person.”

As for other titles, a public librarian in Maryland said, “ Let’s Talk About It was challenged; the book was moved from YA to adult. The adaptation of The Librarian of Auschwitz was also challenged, but kept in the children’s graphic section.”

Ardis Francoeur, a middle school librarian in Massachusetts, said, “‘Heartstopper’was challenged by a parent. She won, it was removed, AND she kept the book.”

Melanie Borror, a middle school librarian in Kansas, said a parent complained about “Heartstopper” “but did not submit a formal complaint. The book remained in circulation, but a note was put on the student’s account so that she was not able to check out any LGBTQIA+ titles after that.”

Maus was challenged at Rachel Backiel’s public library in Florida. “We kept the title on the shelves after an extensive research period to determine if the title was in fact ‘vulgar.’”

Respondents said they could use more support with title selection to ensure they choose age-appropriate works—especially manga. Only 13 percent felt very confident selecting titles for their library. Another 49 percent rated themselves as somewhat confident, and 38 percent were not too confident.

Those who felt more sure of their choices relied on their own knowledge, research, or student recommendations. “I’ve been reading manga for over 20 years, so I feel confident in my selections,” said Emily Tobin, a public librarian in Illinois.

Lisa Towne, a high school librarian in New York, said, “I have consulted book reviews, YALSA recommendations, and student requests.”

Respondents who felt less confident cited factors such as the sprawling nature of manga series or the limits of professional reviews. “It can be overwhelming keeping up with long-running series such as ‘One Piece’ where there [are] also sub-series spinoffs,” said Texas public librarian Melissa Grzybowski.

Susan Farnum, an Illinois public librarian, said, “I feel very confident on older kids’ series, but it seems harder to find age-appropriate ones for elementary and younger middle schoolers.”

Following professional recommendations isn’t enough, added an elementary librarian in South Carolina. “I have found inappropriate material for children in some books that were recommended for that age range (such as nudity and cursing).”

How can reviewers help librarians make informed decisions about graphic novels? Content warnings would help, suggested a public librarian in Rhode Island. “We shelve manga entirely in the teen area, and some of our titles probably skew toward adults. It’s hard to know what’s appropriate, especially for younger teens and middle schoolers.”

As for adaptations of novels, a public librarian in Wisconsin listed these review guidelines: “How much does it diverge from the original form of the story? Does the retelling offer anything the original format doesn’t? For example: simpler language, increased diversity, the removal or addressing of outdated story elements. Is the art any good?”

Ultimately, librarians say it’s worth the research to be able to hand students material they actively want to read. Emily Lail, a public librarian, said even reluctant parents are “happy their children are reading anything.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a writer and editor.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!