Review of the Day – The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler by John Hendrix

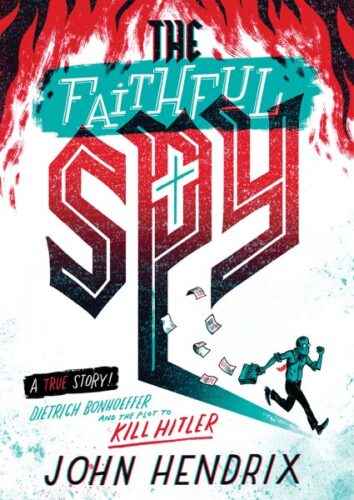

The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoefer and the Plot to Kill Hitler

The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoefer and the Plot to Kill Hitler

By John Hendrix

Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-4197-2838-9

Ages 10 and up

On shelves September 4th

In this life, it can be difficult to find absolutes. Absolute good. Absolute evil. Absolute good in the face of absolute evil. For many of us, the world can be a gray and murky place, where the sheer complexity of each individual human does away with those archaic, grandiose declarations of what is and is not “sinful”.

And then there’s Hitler.

Boy, you just couldn’t have designed a better baddie if you tried. Not a shred of a redeeming quality clings to his form. Thanks to him, WWII really did become that old-fashioned reckoning between bad and good that WWI had failed to encompass. Still, even when you have people fighting Nazis, there’s complexity under the surface. Years ago I remember reading an article, possibly in the New Yorker, possibly a book review, that discussed the culpability of the Germans under Hitler’s power. Surely they weren’t all bad, were they? Or were they? Did they swallow his rampant nationalism with glee or was it force-fed? And what does it feel like to live in a world where the very ground beneath your feet feels like it’s slipping away from under you? Where every single human being living under a mad dictator must wrestle with his or her own conscience regularly? Their own soul? This would be heavy material for a book for adults, but for author/illustrator John Hendrix that challenge could not be enough. He had to make it comprehensible to a 5th grader. I know from working in children’s rooms for years that kids have a fascination with WWII. Some of that comes from the comfort of knowing America was on the side of good (a reassurance we need increasingly these days), but some of it may also be a fascination with what it took out of individuals like the pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer to fight the Nazi tide. I won’t lie to you. This book is chock full of Christianity with a capital “C”. Yet regardless of your denomination, or lack thereof, it’s the combination of history, personal fear, moral implications determining the greater good, and old-fashioned Hitler assassination attempts (can’t forget those) that turn this heavily illustrated title from mere historical piece to downright master-piece. Kids, you ain’t never read anything like this puppy before. And I’ll warrant you won’t ever again.

He was born in 1906, in Germany, to a large, loving family of brainiacs. But in the midst of scientist siblings, Dietrich Bonhoeffer felt an overwhelming calling to the Christian faith. You could say he was a born theologian, and maybe he could have had an uneventful life of Christian fellowship had WWI not gotten in the way. From his broken nation, Dietrich traveled. He made a pilgrimage to Rome, and then a very different one to Harlem. He saw prejudice, great faith, and the power of community, and when he returned to Germany he was determined to put what he had learned into action. Little could he know that Adolf Hitler’s rise was on the horizon. When confronted with the dictator, Heinrich did everything he could to aid the resistance. Through his words and his deeds, author/illustrator John Hendrix heavily illustrates a gripping history that grapples with mighty questions about personal faith and what happens when following your beliefs puts you in the greatest danger of your life.

A biographer gives form and function to a human life. A children’s biographer must then additionally frame that form in a story with heroes, villains and, ultimately, some kind of lesson to be learned. The people we commend as the greatest of heroes are those that lend themselves to grand, eloquent storytelling. This is familiar territory for children’s book biographies. The Faithful Spy, however, isn’t content to stay in familiar territory. No doubt you will hear people argue about its age range. They will say that the book should never have been marketed to children and that due to the complexity of the ideas inside, to say nothing of the presence of Hitler himself, this should be purchased only for young adult collections. But to say that denies that children and middle schoolers are capable of reading, comprehending, and processing moral complexity. Let’s put it another way. Few historical works for children will proffer the idea that all German Christians during WWII weren’t dyed-in-the-wool Nazis. In an era when nationalism is on the rise in countries across the globe, it is a great good to teach kids about a time when blind and displaced loyalty to a country led to unspeakable evil. Hendrix doesn’t have to spell out the parallels to the times in which we live. Have faith in the kids. They’re going to be able to get there on their own. The author is just laying the facts out before them. He trusts their intelligence. We, the adults, would be wise to do the same.

A biographer gives form and function to a human life. A children’s biographer must then additionally frame that form in a story with heroes, villains and, ultimately, some kind of lesson to be learned. The people we commend as the greatest of heroes are those that lend themselves to grand, eloquent storytelling. This is familiar territory for children’s book biographies. The Faithful Spy, however, isn’t content to stay in familiar territory. No doubt you will hear people argue about its age range. They will say that the book should never have been marketed to children and that due to the complexity of the ideas inside, to say nothing of the presence of Hitler himself, this should be purchased only for young adult collections. But to say that denies that children and middle schoolers are capable of reading, comprehending, and processing moral complexity. Let’s put it another way. Few historical works for children will proffer the idea that all German Christians during WWII weren’t dyed-in-the-wool Nazis. In an era when nationalism is on the rise in countries across the globe, it is a great good to teach kids about a time when blind and displaced loyalty to a country led to unspeakable evil. Hendrix doesn’t have to spell out the parallels to the times in which we live. Have faith in the kids. They’re going to be able to get there on their own. The author is just laying the facts out before them. He trusts their intelligence. We, the adults, would be wise to do the same.

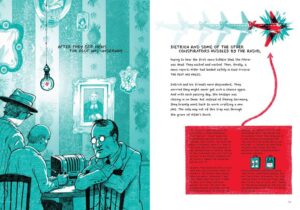

Now for the good news. We live in one of the most exciting times to read nonfiction for kids in American history. I say this because not only are we seeing a significant upsurge in fabulous nonfiction books for kids, increasing every year, but we’re seeing a simultaneous surge in discussions by gatekeepers and professionals on what is and is not a good idea when critiquing these books. Making up facts to support a story? Bad. Making up facts to support a story and then confessing to it in the endpapers? Less bad, but annoying. Fake dialogue? Bad. Fake dialogue that makes it very clear which lines are made up and which are real? Less bad, but potentially confusing. Fake dialogue in cartoon speech bubbles, while the real quotes have asterisks to avoid any and all confusion? Untried until now. Why? Because there’s a new kind of book for children out there that hasn’t yet been the subject of sufficient discussion. You see, while there may be more quality nonfiction for kids being published today than ever, there aren’t that many nonfiction comics for kids (Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales, notwithstanding). What few that there are, however, have made for an interesting set of alternative rules when it comes to dialogue. Here’s how it falls out:

– We acknowledge that any nonfiction book for kids that is illustrated is automatically incorporating fictional elements because no illustration, short of one based on a photograph (and even those were often staged), is “real”. It relies on the artist’s imagination to come to life.

– Furthermore, we understand that comics and graphic novels are, by their nature, heavily reliant on illustration.

– Therefore, when fake dialogue is incorporated into a comic strip on a page, it becomes part of the illustration itself. And since we’ve already established that all readers understand that illustrations are inherently fictional, by extension any words that appear in those illustrations would have to be considered fictional too. The author/illustrator isn’t leading the reader astray, then, because the reader is aware that direct quotations on a page found within distinct quotations marks are to be judged differently than speech bubbles in a sequential art sequence.

By the way, I just made all of that up, but it sounds right to me. There’s more than a hint of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics lurking in those rules, but Scott published his book long before the massive rise of the illustrated nonfiction book for older child readers. None of us could have predicted a need for this kind of clarification. Hendrix, for his part, is crystal clear about what is and is not true in his dialogue. On page 8 he even creates a two-panel spread of 4-year-old Dietrich asking his mother two theological questions. One panel has no asterisk and the other one does. Below, Hendrix notes that “Texts marked with an asterisk denote direct quotations from original sources. Dialogue or spoken words without an asterisk should be read as speculative.” There is no chance, then, of confusion when reading the more comic book-like parts of history. And, as I have mentioned, even without this clarification I’d say he was on solid ground since I consider comics art and art is, inherently, both fictional and unavoidable in illustrated nonfiction works for kids.

By the way, I just made all of that up, but it sounds right to me. There’s more than a hint of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics lurking in those rules, but Scott published his book long before the massive rise of the illustrated nonfiction book for older child readers. None of us could have predicted a need for this kind of clarification. Hendrix, for his part, is crystal clear about what is and is not true in his dialogue. On page 8 he even creates a two-panel spread of 4-year-old Dietrich asking his mother two theological questions. One panel has no asterisk and the other one does. Below, Hendrix notes that “Texts marked with an asterisk denote direct quotations from original sources. Dialogue or spoken words without an asterisk should be read as speculative.” There is no chance, then, of confusion when reading the more comic book-like parts of history. And, as I have mentioned, even without this clarification I’d say he was on solid ground since I consider comics art and art is, inherently, both fictional and unavoidable in illustrated nonfiction works for kids.

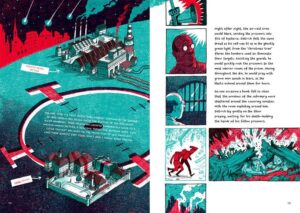

But let’s stop a moment and talk about Hendrix’s art. How do you describe it, really? The man cultivates a style that I’ve been struggling to categorize for years. Were I better acquainted with the history of design I might be able to put it into words. I mean, with its heavy reliance on typography (far more than any other American children’s illustrator I’ve ever encountered) you could say that Hendrix is a ribald combination of Joe Sacco, 1920s Soviet art, and P.T. Bridgeport. Hendrix would probably add influences like Josh Cochran and Al Parker, but while I see where he’s coming from, his style is entirely his own. How he brings this style to bear on a work of nonfiction is particularly interesting when you consider that even five years ago I doubt he could have gotten this book published in this form. Neither fish nor fowl, it isn’t a graphic novel nor a straight block of text. Its intermingling of image and words is a uniquely 21st century creation of a post-Brian Selznick era. And what art it is. It’s not just the typography, beautiful though that might be. Look at the way he draws you close then casts you at a distance, looking down on the action from above. Look at the plethora of maps, graphs, and comic panels. Look at how he renders Dietrich, making the reflection on the man’s lenses obscure his eyes. Why does Hendrix do this? Scott McCloud once pointed out that when you simplify a drawn character, the process of that simplification makes the character more relatable to the reader. When you can’t see Dietrich’s eyes you can ascribe any thought you want to his frame. Notice too that the glasses appear when he’s coming to America, where his eyes will be opened in a different sense. It all comes together.

I mentioned earlier that a lot of kids have a great and abiding affection for WWII, the easiest of the relatively recent wars to comprehend. WWI, in contrast, is a mess that I may still not fully understand to this day. Fortunately, comics have come to provide an ideal method for parsing out complex historical ideas. Take Nathan Hale’s Treaties, Trenches, Mud, and Blood. That was an entire book where WWI’s participants were reduced to animals and critters (bulldogs are England, cocks are France, bunnies are America, etc.) and it worked. Hendrix in The Faithful Spy finds himself with a different problem. He cannot explain Hitler’s rise without delving into WWI and its aftermath. But explaining the WHOLE war would bog down the story. This isn’t supposed to be a treatise on the Kaiser, after all. It’s about Bonhoeffer! So what to do? The solution Hendrix hits on is to reduce WWI to a single two-page spread with mixed results. Certainly, he is able to create something visual that hints at the horrors of the time and the toll it took on the German people. To do this, though, he must cram a lot in. Tiny text, a sidebar that explains the cost of inflation between 1921 to November 1923, a mention of the end of the Monarchy, sanctions, defeat, and the Treaty of Versailles . . . it’s a lot to take it. Maybe too much. May as well just hand them the Hale book at that point. The important thing is to know that it happened.

Undoubtedly the Christianity in the book is going to catch some folks by surprise. Never mind the word Faithful in the title. Never mind the cross floating there in the dead, smack center of the cover. They’re going to be surprised. Hendrix is Christian himself, and I suspect only he could have brought Dietrich’s works to life. After all, the book covers an amazing array of information about its subject’s beliefs. There is Dietrich’s early decision that the true church of God would have to be a revolutionary body. His understand that “a real faith demanded action or it was no faith at all.” And, most important of all, the central theological question of whether or not God would forgive the murderer of a tyrant. “Are there moments in history when ethical people must take extreme actions, even if those are against their moral code?” The fact of the matter is that the central idea at the heart of Bonhoeffer’s life is this question: What the duty of a single Christian, of an average human, in the face of overwhelming evil?

Undoubtedly the Christianity in the book is going to catch some folks by surprise. Never mind the word Faithful in the title. Never mind the cross floating there in the dead, smack center of the cover. They’re going to be surprised. Hendrix is Christian himself, and I suspect only he could have brought Dietrich’s works to life. After all, the book covers an amazing array of information about its subject’s beliefs. There is Dietrich’s early decision that the true church of God would have to be a revolutionary body. His understand that “a real faith demanded action or it was no faith at all.” And, most important of all, the central theological question of whether or not God would forgive the murderer of a tyrant. “Are there moments in history when ethical people must take extreme actions, even if those are against their moral code?” The fact of the matter is that the central idea at the heart of Bonhoeffer’s life is this question: What the duty of a single Christian, of an average human, in the face of overwhelming evil?

In his Author’s Note at the end, Hendrix says that one point of this book was to show how a Hitler can rise. “Despite the lessons learned from the horrors of World War II, recent history has shown humanity has not been permanently vaccinated against tyrants. We never will be . . . The line between national decency and a descent into fear and hatred is, and always will be, razor thin.” Now we live in a country where our children are facing their own tyrants and making their own hard choices. Do I walk out or remain? Stand or take a knee? Like it or not, many Americans bear much in common with Dietrich. The days when those on the more privileged side of the spectrum could blissfully float about without noticing the state of the world around them are gone. Someone once pointed out that when you raise a generation on books like Harry Potter and The Hunger Games, you shouldn’t be too surprised when the children rise up against the tyrants. Our children have been told for years whom they should emulate. Finally, they’re being given a hero that equated faith and love with action and sacrifice.

The time for more of those heroes is now.

On shelves September 4th

Source: Galley sent for review from publisher.

Like This? Then Try:

- Treaties, Trenches, Mud, and Blood by Nathan Hale

- March by John Lewis

- Gandhi: His Life, His Struggles, His Words by Élisabeth de Lambilly & illustrated by Séverine Cordier & translated by Robert Brent

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!