AAPI Women Audio Narrators on the Joys and Challenges of the Job

Five women of Asian descent discuss the joy of telling resonant stories, handling vocabulary in unfamiliar languages, and other topics.

Diverse stories on the page deserve authentic voices in the ears. For Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, we gathered five women of Asian descent to talk about their aurally literary endeavors. Now is certainly an encouraging time to be a narrator: the audiobook industry is one of publishing’s fastest growing segments; according to the Audio Publishers Association, listeners are skewing younger and more diverse. Such proliferation perhaps isn’t surprising with the amplified diversification of titles for readers of all ages. Amid increasing opportunities, being an Asian American narrator is not without its challenges. And so, we got to talking about unfamiliar languages, mispronunciations, limited communication, and the possible need for sensitivity listens. Narrators also had plenty to extol, particularly about their mutual joy of telling resonating stories.

|

“I have never felt more fulfilled in my artistic career than I do at this moment,” says Indian American audiobook narrator Reena Dutt, a former film producer and on-camera actor. A studio visit with her audiobook-producer roommate resulted in Dutt’s casting in Asha and the Spirit Bird by Jasbinder Bilan (2020). Her newest narrations include Saadia Faruqi’s The Partition Project and Hena Khan’s Drawing Deena.

Farah Kidwai’s musical training as a classical singer has served her well in the studio. The Pakistani American, Muslim voice actor booked her first audiobook, This House of Clay and Water by Faiqa Mansab, in 2022 after a casting agent found her name on the VGM VO (Voices of the Global Majority Voiceover) List. Her latest is Hope Ablaze by Sarah Mughal Rana.

Boredom from her career as a lawyer led Mandarin-fluent voice actor and singer Sunny Lu to soul-search for her dream job. The first gigs for Lu, who is Taiwanese Chinese American, were two Josie Tucker mysteries by EM Kaplan; her latest is Kelly Yang’s Finally Heard.

When a friend told VyVy Nguyen, a Vietnamese American actor, that Angie Chau’s Quiet as They Come (2013) needed narrators who could pronounce Vietnamese names and words, Nguyen got her first gig. Her latest one is The Last Bloodcarver by Vanessa Le.

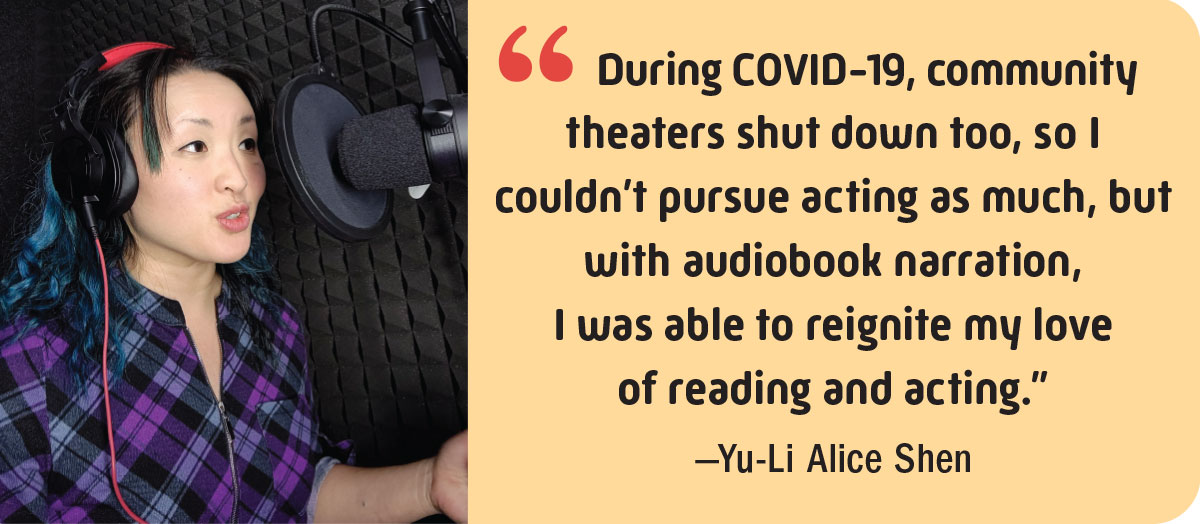

Taiwanese Chinese American Yu-Li Alice Shen is a playwright, actor, and English and creative writing professor. Her audiobooking started during the pandemic when her college voice professor, legendary veteran narrator Andi Arndt, gathered alumni to pilot a Zoom class on narration for beginners. Shen’s debut was The Vegan “Beef” Guide by Lyanna K. Peterson (2021); her most recent is Summer at Squee by Andrea Wang. |

Terry Hong: How often are you cast because of your “matching” ethnic heritage? Are you also cast for other Asian backgrounds?

Nguyen: When I started out, I was only asked to narrate books written by Vietnamese American authors. My voice skews a bit younger, so I read a few high school romances. The exposure of those books helped expand my reach to casting directors who thought I would be a good fit for other YA books that had nothing to do with my being Asian. Last year, half the books I narrated had nothing to do with my Vietnamese heritage.

Lu: I am often cast in books where the protagonist is of Chinese and/or Taiwanese descent, but not characters of other Asian backgrounds. However, characters from other racial and/or ethnic backgrounds might appear in books that I’m narrating as secondary characters. I have also been the protagonist where the racial/ethnic background is not specified.

Dutt: Most producers I work with think of me for South Asian content, and primarily YA work. Some publishers are more people-driven than culture-driven, and they match me with stories/topics I’m passionate about—YA, feminist literature, self-help/motivation, and light romantic comedies.

Shen: With [the big publishers], I am almost always cast as Taiwanese/Chinese characters, oftentimes tweens, and a couple times as biracial romantic leads, though I am not biracial. I rather enjoy being tapped for auditions requesting Asian ancestry because I feel like they are roles written for me and my specific lived experience. With indie novelists, I’ve narrated characters whose ethnicities are open or who were originally white but the author liked the accent/language background I bring for primary and secondary characters. I especially liked breaking into the YA dystopian fantasy and fae high fantasy genres.

Kidwai: All my audiobooks, with the exception of an upcoming project, have been by and about South Asian Muslim women like myself. I feel very honored to bring their stories to life in the booth. There’s something incredible about amplifying narratives written by people who are so much like me, whose worlds are so similar to the one I grew up in. That said, I definitely worry about pigeonholing and am excited to expand into other audiobook genres.

Do producers/directors offer any sort of training, support, or coaching, particularly regarding vocabulary in an unfamiliar language? If not, how do you prepare?

Nguyen: I appreciate that producers will often try to get the necessary pronunciation references when I have to deal with languages beyond Vietnamese, whether it’s through contacting the author directly or grabbing examples on Pozotron [an audiobook proofing service]. I will also utilize resources like Forvo [an online pronunciation dictionary] and YouTube and try to speak with native speakers.

Dutt: Sadly, there hasn’t been much support for South Asian language pronunciations, so the work does double up for someone who speaks, reads, and writes multiple languages but is not necessarily fluent. I am slowly learning more about all the many resources out there, but there’s nothing like talking with folx from the culture to really pinpoint all the nuance.

[Also read: "31 YA Novels for Every Day of AAPI Heritage Month and Beyond"]

Shen: I am fluent enough in spoken Mandarin that I can figure out the intonations on my own. But to clarify homophones, I make a list of words and the producer sends it to the author who then makes audio or phonetic notes. Authors have been quite helpful, recording their own voices and sending YouTube reference videos for certain accents.

A fellow Asian Pacific American editor and I bemoan audiobooks that too often have horrendous pronunciation of foreign languages. Producers and directors can seem culturally insensitive at best, and downright lazy at worst, believing that casting an Asian-looking face with an Asian-sounding name is enough for titles written by authors of Asian heritage. Have such assumptions affected your casting?

Kidwai: I did a project in which my co-narrators, who were South Asian but not Pakistani, mispronounced the names of several characters and Urdu words. There was no communication or quality control from the production company to make sure we were all on the same page.

Lu: I once auditioned for a character from another Asian background, and it involved narrating many words in a language I had never spoken. I felt uncomfortable recording this audition because I did not share the same APA ethnic identity or native language as the book’s protagonist, and the identity was crucial to the story.

Nguyen: I did an anthology series with a story set in Japan. I wasn’t sure why I got assigned to narrate that story, except that I had an Asian background. I wanted to do the best job possible, but the pronunciation references the producers provided were a hodgepodge of Westernized pronunciation and authentic Japanese pronunciation. I told them I would require consistency and asked if they could have one speaker pronounce all the words. But the producers were in a time crunch, so I quickly reached out to a friend who is a Japanese language consultant for television. She saved me.

Dutt: I haven’t dealt with this yet! Many South Asian titles I’m on are a self-record, but when I have had a director, their cultural sensitivity has been generous. I worked with a director who was not from my culture and yet had done so much research regarding nuances in pronunciation and regional differences. That kind of allyship and commitment to cultural nuance is such a gift.

Shen: Thankfully, I have not had to deal with cultural insensitivity. My only slight misgiving has been narrating Chinese/Taiwanese and white biracial roles. I am not biracial, but as an immigrant who identified as a Twinkie in her younger years, I’m familiar enough with the language of duality.

Among this year’s Audie Awards, I noted that a veteran APA narrator’s name was mispronounced by another narrator in the same cast, and a finalist title by a Chinese American author was rife with mispronunciations. What do you think of adding sensitivity listens before release?

Lu: Our job as narrators is to not only bring life to the author’s story, but to do so in a way that is respectful of the characters and of the audience. The increase in APA hate crimes and racism has spurred a lot of soul-searching by authors and narrators alike, and we all want to know what we can do to accurately and sensitively portray a lived experience. This can pose a unique challenge for us as narrators, especially in single-narrator productions with one narrator voicing multiple characters, often from different backgrounds. I think I speak for all of us when I say we all want to be respectful and do the right thing. Adding a sensitivity/authenticity screen is an intriguing idea and could help spark more conversation and move the industry forward.

Nguyen: I support sensitivity listens, but these are issues that also should be addressed prior to even casting an audiobook. When I got chosen to narrate Michelle Quach’s Not Here to Be Liked, I didn’t realize there would be so much Cantonese and Mandarin, and had to work incredibly hard to make sure my pronunciation didn’t butcher the languages. Had I been informed that the Chinese phrases far outnumbered the Vietnamese ones, I probably would have told the producers to cast someone else.

Dutt: Sensitivity listening is an interesting concept on a practical level. With many producers offering gigs that are self-record, I wonder if there’s even the budget to hire an additional person. On an artistic level, at least with some South Asian dialects, there is conflict within regions on whether one pronunciation is more accurate than another, and those ideas are often led by regional/class/upbringing biases. Even with added sensitivity, I don’t know if we can erase 100 percent of the discrepancies and/or biases, but another layer of care would certainly not be declined.

Kidwai: I absolutely support this. I would be so much prouder of some of the multi-narrator projects I have done if we’d have had some meaningful quality control and consistency.

Shen: Echoing all of the above! Also recognizing the disappointing impossibility of full authenticity, considering diverse biases.

If you could advise or compliment producers and directors about anything, what would you say?

Kidwai: Listen to your narrators if they are language or subject matter experts. I have gotten pushback from producers who don’t want to bother the author with my questions for clarification, and that has sometimes affected the quality of my narration. I wish I could speak directly to my authors, or have three-way Zooms with the producer, so that there isn’t an intermediary. It just makes the process so error-prone.

Nguyen: I love it when producers connect us with the other narrators on a multi-narrator project and let us discuss how we’re approaching the characters and even send along voice samples. Even if I’m not able to perfectly mimic another narrator, I can try to capture their general essence and provide consistency.

Dutt: This industry could teach other industries a lot about the value of storytelling, collaboration, colleague-ship. I have never felt more supported and cared for than I have with my audiobook peers—producers, engineers, directors, and narrators alike.

What do you most enjoy about voicing audiobooks?

Shen: I just love reading again. As a full-time English professor, I never read for pleasure anymore. During COVID-19, community theaters shut down too, so I couldn’t pursue acting as much, but with audiobook narration, I was able to reignite my love of reading and acting.

Dutt: Disappearing into a story and having the opportunity to tell it without the worry of being judged on what I look like in my PJs!

Lu: When I finish recording, I often find it hard to say goodbye to the characters because I’ve grown so fond of them and invested in their stories. I also love that, most of the time, I’m putting on a one-person show and it feels like an old-fashioned radio drama. Today, the story is more likely to unfold in someone’s headphones or in the car, but we’ve preserved the same storytelling format, which delights me.

Kidwai: I absolutely love telling stories! We work with our authors to create an important conduit by which a reader can really bond with a story.

Nguyen: I feel so proud to be able to help these authors share their words in a different medium. I’ve worked with several first-time authors and that’s especially thrilling. Whenever I’m particularly excited about a book, I create social media posts related to the story’s themes. For Sunshine Nails by Mai Nguyen, I got a manicure and posed with the book in front of a wall of nail polish. These posts are the cherry on top after doing the hard work in the studio.

Terry Hong is a reviewer for SLJ and LJ who specializes in audiobooks.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!