School Boards Tied Up By Book Bans Face Harassment, Struggle to Address Other Issues

Book challenges overwhelm members seeking to follow library policy and address other district issues.

|

AdrianHillman/Getty Images |

Book challenges don’t just prevent librarians and teachers from doing their jobs. They’re also an obstacle for school board members, who can find themselves at odds with colleagues and the community as they try to uphold their district’s policies—sometimes losing elections in the process.

Board members and literacy advocates describe harassment, insults, and even death threats over districts’ attempts to review and retain books on library shelves. They say that the book-challenge movement prevents boards from conducting business and may discourage people from running for seats.

“We have all the hysteria,” says Skeeter Hubert, board of education president of Conroe ISD in Houston.

People come to the meetings and say the district should not be “exposing the children to these books,” and then read aloud sexual excerpts from books that aren’t in the district’s libraries, while children are at the meetings, he says.

“They are absolutely doing the very thing they are accusing us of doing, which we are not,” says Hubert, who will be stepping down from the board when his term ends. “It’s the most bizarre thing.”

In the North Hunterdon-Voorhees (NJ) Regional High School District, book challenges became “a very high-level distraction” from the work of the board, according to the board’s former president Robert Kirchberger.

Hubert, who served on the Conroe ISD board for 10 years and as president for four, says that most of the people challenging books at meetings don’t have students in the district and don’t know whether the district even carries the books. “We’re having to fact-check them as they read,” he says.

When Hubert didn’t decide in favor of the book challengers, he got death threats.

“I’ve had people show up to public meetings and physically try to fight me. I’ve had all kinds of names being called,” he says.

Anne Russey, codirector of the Texas Freedom to Read Project, says that it’s hard to watch the same accusations that teachers and librarians receive—of “giving pornography” to kids—being aimed at board members.

“Just like it weighs on librarians, and it weighs on educators, and it weighs on parents that are advocating against these book bans, it weighs on the board members, too,” she says. School board members have been attacked by Libs of TikTok and boards have received bomb threats, according to Russey.

“It’s just really discouraging, and it’s dangerous,” she says.

Many school boards rely on a committee of community members to review a book and recommend it for retention or removal. Hubert says that in following this policy with its community review committee, Conroe ISD has moved some books to upper grades or removed them altogether. For instance, Fun Home by Alison Bechdel was removed because of the illustrations of sexual activity.

Through a voluntary audit, the board also determined that some donated books or substitutions on book orders were inappropriate. Now all books are vetted before going into circulation.

Sometimes, a board will prioritize complaints from people who are reading passages out of context, “shocking school boards into reaction versus considering a book in its entirety,” says Russey.

Stephana Ferrell thinks fear is a factor as well. The director of research and insight at the Florida Freedom to Read Project says that some school board members might be afraid to voice their opinions on a book.

Board members reading the book can make a difference. Ferrell recalls when a board member in Flagler County, FL, who was reviewing Sold by Patricia McCormick—about child trafficking—had intended to vote to remove the book. Instead, she read it, and voted to retain it. She also told those at the board meeting that she gave it to her 15-year-old daughter. She wanted her to read it before she left for college to better protect herself and so she would understand the power and control people can have over you.

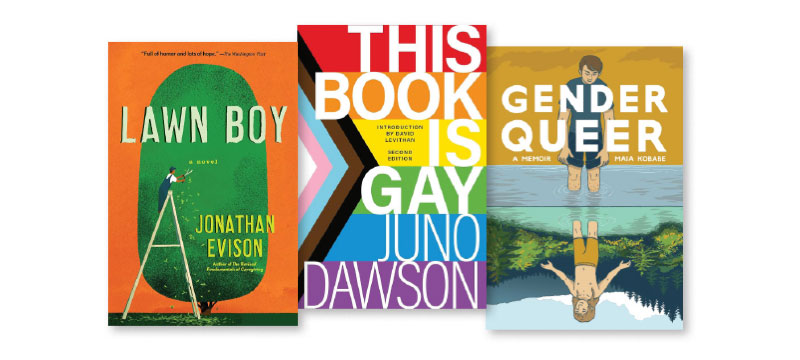

Kirchberger, in New Jersey, says that the five books challenged in his district, including Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison, This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson, and Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, all featured LGBTQIA+ themes and characters. When he read them, he decided the books were “relevant to the readers who would be interested in taking them out.”

In the end, the North Hunterdon-Voorhees board voted to retain the books. But even after the vote, the issue wasn’t settled. People spent months criticizing the decision during meetings. The challenges pulled the board into a never-ending back-and-forth with the public, taking time away from more consequential actions, says Kirchberger.

He doesn’t think that the book-challenging movement is organic. Arguments over COVID-19 mask requirements and virtual school morphed into book challenges and fights over bathroom and locker room access for transgender students, he says. “I think it was a playbook rather than the heartfelt concerns of the community.”

After the North Hunterdon-Voorhees board voted to retain the five books, candidates ran on a “parental rights” platform. They won two seats, including Kirchberger’s.

In Texas, Hubert says, three board members won seats by campaigning against “porn” in school libraries.

“We never had one book challenge before they came on the board,” he says.

Those board members also opposed returning other books to the shelves, according to Hubert. “Any kind of book that has anything to do with a gay character or transgender character, they want it removed.”

He adds, “Whether I agree or disagree with that lifestyle, it doesn’t matter. We have a slogan in Conroe ISD, ‘All means all.’ All kids should be represented, and all kids should have access to age-appropriate reading material.”

Kirchberger, who had served on the board for six years, thinks the country’s polarized climate “has dragged school boards into a politicized state that I don’t think is healthy for the mission of the school board.”

Russey agrees, adding that it is also hurting the future of school board candidates.

“I think it is probably limiting the number of people who are willing to throw their hat in the ring, because they see how the community or politicians or these outside activist groups that travel around the state pulling these read-aloud stunts are treating school boards.”

Hubert, whose term has ended, is hoping a new generation of leaders will step up.

Ultimately, he says, the book-challenge movement is “about trying to demolish and demoralize public education.” He says the board members who favor book challenges don’t understand the importance of balancing the budget or keeping tax rates low.

“Our district is suffering, because as goes the school board, so goes the district,” says Hubert. “And when there’s nothing but controversy and argument and name-calling going on, it’s just a very, very bad look for our community as a whole. It’s just very sad.”

Russey believes that book challenges have become a tool of political groups and candidates to erode trust in the public school system. “If you can convince enough parents that their school libraries are full of inappropriate materials, then people may be less likely to trust their public schools or to advocate for fully funding public schools.”

In the November election in Florida, it was a mixed bag of results in school board elections. The more ideologically extreme candidates did win some races; the more moderate candidates succeeded in others. Overall, Ferrell found some hope in the results.

While she is concerned that book removals will continue, she’s hopeful that in most districts, “the rejection of the more ideologically extreme candidates will re-center the work going forward on the learning needs of all students.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a freelance writer and editor.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!