Reading Recommendations for Filipinx* Americans

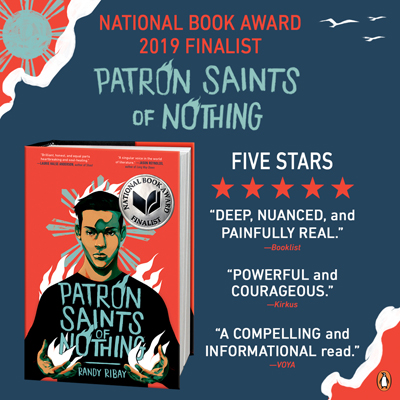

Randy’s latest book, Patron Saints of Nothing, is a powerful coming-of-age story about grief, guilt, and the risks a Filipino-American teenager takes to uncover the truth about his cousin's murder. It has received five starred reviews and was selected for the National Book Award Longlist.

by Randy Ribay

Randy Ribay was born in the Philippines and raised in the Midwest. He is the author of After the Shot Drops and An Infinite Number of Parallel Universes. Randy’s latest book, Patron Saints of Nothing, is a powerful coming-of-age story about grief, guilt, and the risks a Filipino-American teenager takes to uncover the truth about his cousin's murder. It has received five starred reviews and was selected for the National Book Award Longlist. He earned his BA in English Literature from the University of Colorado at Boulder and his Master's Degree in Language and Literacy from Harvard Graduate School of Education. He currently teaches English and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

It wasn’t until college when I read my first book by or featuring a Filipinx or a Filipinx American person. I still remember the feeling of disbelief as I saw familiar names, places, foods, etc. in print for the first time. “Oh, people actually write about adobo?” I thought. It seems obvious someone would, of course, but when you grow up never seeing a significant part of yourself on the page, it truly is a revelation to have your experiences validated in such a simple way, a way that helps you understand that your existence is worthy of artistic portrayal.

Despite Filipinos being the third largest immigrant group in the United States, we remain one of the most underrepresented groups in the media. But I’m hopeful things are shifting (of course, we still have MUCH more shifting to do). In recent years there’s been an increase in Filipinx and Filipinx American representation in children’s literature, books that I wish were on my childhood shelf but am grateful exist for kids coming up today.

For the little ones, there’s Cora Cooks Pancit, written by Dorina Lazo Gilmore and illustrated by Kristi Valiant, about a young girl helping her mom cook the staple dish. Christina Newhard’s Kalipay and the Tiniest Tiktik, illustrated by Happy Garaje, shares the story of a young girl trying to deal with bullying with the help of an interesting new friend. Journey for Justice, written by Dawn Mabalon & Gayle Romasanta and illustrated by Andre Sibayan, tells of the life of FilAm labor activist Larry Itliong, who helped organize the Delano Grape Strike. And keep an eye out for Michelle Sterling’s forthcoming When Lola Comes, illustrated by Aaron Asis, about a girl longing for her lola after she returns to the Philippines.

For middle grade readers, Filipinx representation can be found in all of Newbery Award-winner Erin Entrada Kelly’s work, from her debut Blackbird Fly to her latest novel, Lalani and the Distant Sea, which taps into Filipino folklore to craft the story of a girl embarking on a journey in order to save her ailing mother. Marie Miranda Cruz’s Everlasting Nora and Gail Villanueva’s My Fate According to the Butterfly take readers to the Philippines, the former following a girl looking for her mother who’s suddenly disappeared, and the latter confronting the impact of a parent’s drug use upon a girl and her family. Stateside, Mae Respicio’s The House That Lou Built tells of a girl building a tiny house to get some breathing room from her large Filipinx family, while her upcoming Any Day With You centers a family dealing with tragedy. For those looking for something more adventurous, there’s Armando Baltazar’s "Timeless" series, which is set in New Chicago, where historical eras collide.

For teens seeking out Filipinx representation or simply Filipinx authors in YA beyond my own Patron Saints of Nothing, there’s Melissa de la Cruz’s Something in Between, which follows a college-bound Filipina American grappling with the reality of her family’s expired visas. Juleah del Rosario’s 500 Words or Less also delves into the college struggle, while Kate Evangelista’s The Boyfriend Bracket and R. Zamora Linmark’s The Importance of Being Wilde at Heart focus on matters of the heart. Lygia Peñaflor’s All of this is True offers up a thriller wherein a group of teens deal with the fallout of spilling their secrets to their favorite YA writer, while the upcoming A Thousand Fires by Shannon Price—inspired by The Outsiders and The Iliad— imagines gang warfare in an alternate history modern-day San Francisco. For fantasy, check out Roshani Chokshi’s "Gilded Wolves" series, Reno Ursal’s "Bathala" series, and Rin Chupeco’s "The Bone Witch" series. There are also some great Filipinx stories to be found in the collection of Asian fairytale retellings A Thousand Beginnings and Endings, edited by Ellen Oh.

Even though I set out to focus on children’s literature, I can’t help but quickly offer some recommendations for older teen readers and adults: In fiction, there are the FilAm classics America is the Heart by Carlos Bulosan and Dogeaters by Jessica Hagedorn. More recently there’s In the Country by Mia Alvar, America is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo, Insurrecto by Gina Apostol, and The Farm by Joanne Ramos. In nonfiction, Luis H. Francia’s A History of the Philippines offers just that, while M. Evelina Galang’s Lola’s House features the testimonies of Filipinas who survived being “comfort women” during the Japanese occupation of Philippines during WWII. Those looking for memoirs will find no shortage: Alex Tizon’s Big Little Man, Pulitzer-winner Jose Antonio Vargas’s Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen, Grace Talusan’s The Body Papers, and Malaka Gharib’s I Was Their American Dream. Meanwhile, Anthony Ocampo’s The Latinos of Asia and E.J.R. David’s Brown Skin, White Minds explore the complexity of FilAm identity. And those who appreciate poetry should check out works by Nick Carbó, Patrick Rosal, Barbara Jane Reyes, Jon Pineda, Rachelle Cruz, and Jason Bayani.

Compiling this list gives me hope, and I’m confident that there are even more of us out there, ready to expand it, ready to shift this world. When a community is as diasporic as ours is, literature can go a long way toward building a sense of community, each story a thread weaving us closer together. That’s how I eventually found myself. Maybe that’s how you did. And maybe that’s how you will help others do so.

Never forget that it’s not just writers or illustrators who cast this binding magic. Teachers, librarians, reviewers, book bloggers, BookTubers, Bookstagrammers, booksellers, agents, editors, publicists, marketing professionals, salespeople, designers, interns, and others in the industry all play vital roles in determining which stories get told and by whom, and we should never overlook that fact, that power.

*A note on terminology: “Filipinx” has gained popularity in recent years as a gender-inclusive alternative to the default masculine-gendered “Filipino.” However, some feel that replacing the “o” or “a” is simply swapping out the Spanish influence for more American colonialism, given that the letter “x” is not actually used in most traditional Filipino languages. Personally, I use “Filipinx” when referring to the collective community for reasons of inclusivity, but I still tend to use “Filipino” or “Filipina” when referring to those who I know identify as male or female, or on occasions when “Filipinx” simply doesn’t work grammatically.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing