Q & A with Author Deborah Jiang-Stein: Bringing Libraries to Prison Nurseries

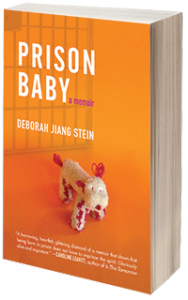

Deborah Jiang-Stein was born in prison to a mother addicted to heroin. Today, she is an author of the memoir Prison Baby (Beacon Press, 2014) and the founder of a nonprofit dedicated to providing life skills and mentoring to incarcerated women, the unPrison Project, which recently announced its partnership with the Children’s Book Council (CBC) to build libraries in prison nurseries in honor of Mother’s Day, May 10, the last day of Children’s Book Week 2015. In Prison Baby, Jiang-Stein chronicled her birth into the prison system, followed by her adoption and a long, twisted journey to overcome the shame of her origins, during which she encountered addictions of her own. As the founder of the unPrison Project, she tours female prisons across the country to speak about her unique origin and experiences, including her time spent in a prison cell with her mother as an infant, as well as her never reconnecting with her birth mother (who is now deceased) after leaving prison and entering the foster care system. Sharing her story not only releases the stigma and shame of her past, says Jiang-Stein, but it provides a bridge for her to talk about the unPrison Project’s training and mentorship program for incarcerated women. The collaboration between the unPrison Project and the CBC will create libraries of books for incarcerated mothers to read with their babies at prison nurseries in 10 states. “Of the 200,000 women in prison in the United States, 80 percent have children. Reading together can be one of the most powerful ways for mothers and their children to stay connected during a prison sentence, but visiting rooms in prisons are vastly underserved and books are hard to come by,” says Jiang-Stein in a prepared statement. SLJ caught up with the formidable founder of the unPrison Project and talked about the shame she used to feel about her past, her ability to uplift others through her experiences and outreach, and her organization’s collaboration with the CBC. Would you share your very unusual beginnings? In many ways, the beginning of my life is like the story of a number of others born to incarcerated parents. My birth mother was a heroin addict and during one of her sentences she was pregnant at the time. She was allowed to keep me as she waged a custody battle with both state and federal authorities and Child Protection Services. I believe she ended up doing six or seven years of a 10-year sentence. I was told that [during] some of my infant time in prison with her, we spent in isolation, or segregation, where she was sent, often, when charged with infractions of prison rules. After [I spent] a year inside, Child Protection Services removed me from prison and placed me in foster care—and from there I was adopted.

Deborah Jiang-Stein was born in prison to a mother addicted to heroin. Today, she is an author of the memoir Prison Baby (Beacon Press, 2014) and the founder of a nonprofit dedicated to providing life skills and mentoring to incarcerated women, the unPrison Project, which recently announced its partnership with the Children’s Book Council (CBC) to build libraries in prison nurseries in honor of Mother’s Day, May 10, the last day of Children’s Book Week 2015. In Prison Baby, Jiang-Stein chronicled her birth into the prison system, followed by her adoption and a long, twisted journey to overcome the shame of her origins, during which she encountered addictions of her own. As the founder of the unPrison Project, she tours female prisons across the country to speak about her unique origin and experiences, including her time spent in a prison cell with her mother as an infant, as well as her never reconnecting with her birth mother (who is now deceased) after leaving prison and entering the foster care system. Sharing her story not only releases the stigma and shame of her past, says Jiang-Stein, but it provides a bridge for her to talk about the unPrison Project’s training and mentorship program for incarcerated women. The collaboration between the unPrison Project and the CBC will create libraries of books for incarcerated mothers to read with their babies at prison nurseries in 10 states. “Of the 200,000 women in prison in the United States, 80 percent have children. Reading together can be one of the most powerful ways for mothers and their children to stay connected during a prison sentence, but visiting rooms in prisons are vastly underserved and books are hard to come by,” says Jiang-Stein in a prepared statement. SLJ caught up with the formidable founder of the unPrison Project and talked about the shame she used to feel about her past, her ability to uplift others through her experiences and outreach, and her organization’s collaboration with the CBC. Would you share your very unusual beginnings? In many ways, the beginning of my life is like the story of a number of others born to incarcerated parents. My birth mother was a heroin addict and during one of her sentences she was pregnant at the time. She was allowed to keep me as she waged a custody battle with both state and federal authorities and Child Protection Services. I believe she ended up doing six or seven years of a 10-year sentence. I was told that [during] some of my infant time in prison with her, we spent in isolation, or segregation, where she was sent, often, when charged with infractions of prison rules. After [I spent] a year inside, Child Protection Services removed me from prison and placed me in foster care—and from there I was adopted.  After you were adopted and went through your own struggles with addiction. How were you able to turn yourself around? My drug and alcohol abuse, which started as a teen, were my way to medicate the trauma and sorrow and confusion from those early years of being moved around. A few years ago, I began speaking openly about my roots in prison, about recovery from addictions, and about how secrecy can cause more harm than the actual facts we’re holding as secrets. I harmed myself more by keeping my prison birth a secret from the world. I never told anyone until my adult life. I first wrote my memoir as a novel, not ready to disclose myself in full about the truth of my story. It took 10 years, and the help many editors and mentors, to finish Prison Baby. I’m grateful to my publisher Beacon Press and my editor Gayatri Patnaik for believing in the story and my work. As part of your work for the unPrison Project, you speak at women’s prisons across the country and share your story. What has been the response? It’s been powerful—I get testimonials from wardens, staff, and guards, and inmates themselves. Most of them have children and lost [them to the foster care system]. Most of them hear the negative side [of what happens to the children of incarcerated mothers], and I can give them a positive side. As someone who had drug issues, what helped you overcome them? I have friends and family who helped and encouraged me. I felt if I could give that [support] back, that would be great. I was given a gift of education, reading, and literacy, and I think that has made a world of difference. I never dreamed I could become anything. My first passion is fiction, and I have a collection of unpublished short stories (that I am currently looking to publish). I eventually was giving freelance writing workshops at school, often with at-risk youth. How did you get into your current advocacy work with incarcerated women? My first access into prison began as a writer, offering writing workshops, and discussing the power of creativity to uplift us. After a few years, instead of a classroom of 20 or so, wardens invited me to speak to the full prison populations and share my story. Now [I stand up before] a filled gym or chapel. Going for a wider reach is now my purpose and mission. I’ve been invited to speak at 31 women’s prisons, and the question and answer periods have the same emotions [and questions]: How will our children see us, how will we be forgiven, and how can we be different and not be back here again? When I see that what I say matters and that women learn from my work, I’m inspired [to believe] that maybe I’m making a change so that someone else might not have to suffer. You now run an organization that helps incarcerated women plan for a successful life upon release. What do you focus on to aid success? The focus of the unPrison Project is on three things: life skills (e.g. noncognitive life skills, anger management, persistence); reading and literacy for the incarcerated and for their children; and a mentoring program similar to “Train-the-Trainer” with a curriculum for women in prison (and men) to learn the craft of how to message their story the way I’ve learned, so that it’s a tool for teaching others. I’ve received specific training for ways to reframe and use my story, and I’m now teaching others what I was given, because I feel it’s my duty and pleasure to give back to my roots. How did your collaboration with the CBC come about? I’ve seen some of the prison nurseries, and I’ve noticed very few children’s books remain and circulate. A visiting room could be a classroom. I reached out to several literacy organizations, and late last year, the CBC and I connected. Within months, the CBC was on board. Things happened very quickly. (Visit the CBC website for a list of participating book publishers.) Our excitement about this wonderful collaboration is because the project addresses literacy and parent-child bonding at the same time. Some of the statistics I’ve found from several literacy councils serve as evidence for why this project matters:

After you were adopted and went through your own struggles with addiction. How were you able to turn yourself around? My drug and alcohol abuse, which started as a teen, were my way to medicate the trauma and sorrow and confusion from those early years of being moved around. A few years ago, I began speaking openly about my roots in prison, about recovery from addictions, and about how secrecy can cause more harm than the actual facts we’re holding as secrets. I harmed myself more by keeping my prison birth a secret from the world. I never told anyone until my adult life. I first wrote my memoir as a novel, not ready to disclose myself in full about the truth of my story. It took 10 years, and the help many editors and mentors, to finish Prison Baby. I’m grateful to my publisher Beacon Press and my editor Gayatri Patnaik for believing in the story and my work. As part of your work for the unPrison Project, you speak at women’s prisons across the country and share your story. What has been the response? It’s been powerful—I get testimonials from wardens, staff, and guards, and inmates themselves. Most of them have children and lost [them to the foster care system]. Most of them hear the negative side [of what happens to the children of incarcerated mothers], and I can give them a positive side. As someone who had drug issues, what helped you overcome them? I have friends and family who helped and encouraged me. I felt if I could give that [support] back, that would be great. I was given a gift of education, reading, and literacy, and I think that has made a world of difference. I never dreamed I could become anything. My first passion is fiction, and I have a collection of unpublished short stories (that I am currently looking to publish). I eventually was giving freelance writing workshops at school, often with at-risk youth. How did you get into your current advocacy work with incarcerated women? My first access into prison began as a writer, offering writing workshops, and discussing the power of creativity to uplift us. After a few years, instead of a classroom of 20 or so, wardens invited me to speak to the full prison populations and share my story. Now [I stand up before] a filled gym or chapel. Going for a wider reach is now my purpose and mission. I’ve been invited to speak at 31 women’s prisons, and the question and answer periods have the same emotions [and questions]: How will our children see us, how will we be forgiven, and how can we be different and not be back here again? When I see that what I say matters and that women learn from my work, I’m inspired [to believe] that maybe I’m making a change so that someone else might not have to suffer. You now run an organization that helps incarcerated women plan for a successful life upon release. What do you focus on to aid success? The focus of the unPrison Project is on three things: life skills (e.g. noncognitive life skills, anger management, persistence); reading and literacy for the incarcerated and for their children; and a mentoring program similar to “Train-the-Trainer” with a curriculum for women in prison (and men) to learn the craft of how to message their story the way I’ve learned, so that it’s a tool for teaching others. I’ve received specific training for ways to reframe and use my story, and I’m now teaching others what I was given, because I feel it’s my duty and pleasure to give back to my roots. How did your collaboration with the CBC come about? I’ve seen some of the prison nurseries, and I’ve noticed very few children’s books remain and circulate. A visiting room could be a classroom. I reached out to several literacy organizations, and late last year, the CBC and I connected. Within months, the CBC was on board. Things happened very quickly. (Visit the CBC website for a list of participating book publishers.) Our excitement about this wonderful collaboration is because the project addresses literacy and parent-child bonding at the same time. Some of the statistics I’ve found from several literacy councils serve as evidence for why this project matters: - More than 70 percent of the incarcerated in the United States read at a 4th grade level or below. Literacy is learned, and illiteracy is passed on from generation to generation. When an adult improves reading skills, the potential is passed to her children.

- 85 percent of juveniles who interface with the court system are functionally illiterate, and 60 percent adults in prison are functionally illiterate.

- Prison records show that if an inmate receives literacy help, the chance of returning to prison is 16 percent, as opposed to 70 percent for those who receive no help. Translate this into tax dollars: taxpayer costs for incarceration range from of $25,000 to over $55,000 per year per inmate, depending on the state.

Incarcerated Women Facts

• The incarceration rate for women has surged: 800% increase over a 20 year period, twice that of men.

• The majority of women in prison are sentenced for nonviolent drug or alcohol related offenses.

• It costs a state more than seven times as much to imprison a woman than to provide her with drug treatment services.

• The ACLU has found a reported 85 to 90% of women in prison have a history of physical and sexual abuse. Many turned to drugs to self-medicate. The prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual violence against women is a significant contributing factor to women’s use of illegal drugs.

• About 75% of women in prison have diagnosable mental health problems.

• One in 25 women is pregnant when she goes into prison, and the majority of women in prison are mothers, and most were the primary caretaker of their children prior to incarceration.

• Two-thirds of women in prison in the United States are women of color.

• According to the American Civil Liberties Union, the United States has less than 5 percent of the world's population but 25% of its prisoners.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!