Librarians Collaborate to Support English Language Learners and Their Families

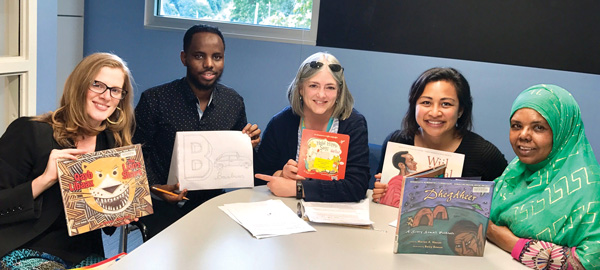

The Baro Af-Soomaali alphabet book is the work of Somali mothers and

their children, who collaborated with the Seattle Public Library,

a local Somali poet, and various organizations to create a picture book that allows sharing

of language and culture among generations of families and in the community.

Photos courtesy of Seattle Public Library

It was a meeting of the five families, but this one—with some assistance from the Seattle Public Library (SPL)—led to what may be the country’s first crowdsourced book in the Somali language.

When Seattle’s Somali population sought more materials to help parents and children communicate in their native language and share their culture and customs, the library set out to develop a pilot project that would allow for family learning and promote cultural understanding—then possibly be scaled for wider use.

The result was Baro Af-Soomaali, which means “Learn Somali,” an alphabet board book now found at the public library, in every elementary school in Seattle, and on Amazon.com. In February, Seattle’s mayor, Jenny Durkan, joined hundreds of city residents to fete the launch of the book, which was a collaboration between SPL and the SPL Foundation, the Somali Family Safety Task Force, Seattle Public Schools (SPS), and the Seattle Housing Authority, which houses 10 percent of the city’s public school students.

The result was Baro Af-Soomaali, which means “Learn Somali,” an alphabet board book now found at the public library, in every elementary school in Seattle, and on Amazon.com. In February, Seattle’s mayor, Jenny Durkan, joined hundreds of city residents to fete the launch of the book, which was a collaboration between SPL and the SPL Foundation, the Somali Family Safety Task Force, Seattle Public Schools (SPS), and the Seattle Housing Authority, which houses 10 percent of the city’s public school students.

Farhiya Mohamed, who runs the Somali task force, brought traditional brooms, teapots, and other artifacts back from a visit to her native Mogadishu. The items were photographed and incorporated into the book. Mohamed Shidane, a Seattle-based, Somali-speaking poet, worked with five local families to decide which motifs would make it in.

The collaboration sparked “intergenerational dialogues between parents and children about their culture,” says Kathlyn Paananen, housing and education manager at SPS.

“Somali parents really appreciated that they can now read to their kids,” says Mohamed, who notes that families often use code-switching and incorporate some Somali words. “For example, my mom tells my niece, ‘Could you bring me the jalmad?’, the Somali word for kettle, one of the items depicted in the book.”

What was slated to be a self-published project attracted a publisher, Applewood Books. A thousand copies were printed, and royalties from Baro Af-Soomaali will go toward funding similar projects.

What was slated to be a self-published project attracted a publisher, Applewood Books. A thousand copies were printed, and royalties from Baro Af-Soomaali will go toward funding similar projects.

Bootstrapping, tapping parental expertise, and adapting to shifting demographics: The tale of Baro Af-Soomaali illustrates how librarians across the country are grappling with how best to meet the needs of English Language Learners (ELLs), a growing segment of the student body. In the face of shrinking budgets and a charged political climate that has given rise to some anti-immigrant sentiment, they’ve conjured up several promising ways to increase ELL engagement, including multilingual storytimes; collaborating with parents; and other native speakers on original materials, and developing an online catalogue of books, poems, and songs in a wide variety of languages. They’ve independently taken on the task of building collections that meet the needs of their specific ELL populations. They’ve pushed to streamline access to resources across city and state lines and partnered with technology providers, independent makerspaces, and large corporations in an attempt to build scalable solutions.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, there were an estimated 4.6 million ELL students—or 9.4 percent of the total U.S. public-school population—in the 2014–15 calendar year, up from 4.3 million (9.1 percent) a decade earlier. Between 2009 and 2014, the percentage increased in more than 25 states, with five seeing growth of more than 40 percent. As the ELL population grows, so does its diversity. While librarians may have the picture books to captivate a native speaker of Spanish or French, they say it’s much more difficult to find stimulating materials for a child who communicates in Tagalog, say, or Farsi.

Educators know the scale of the challenge is considerable, and meeting it will require a full-court press, multigenerational outreach, and long-term commitment.

“When you are talking about ELLs in schools, you are talking about parents and grandparents,” says Mimi Lee, who chairs the Ethnic & Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table for the American Library Association. “They are pretty much the foundation of your outreach. Your technological materials, your books, they’re your inventory.” But any truly effective effort to serve ELLs will require long-term coordination across all points of outreach, from public and school libraries to broader citywide services.

“Serving immigrant communities,” Lee says, “is not a one-day deal.”

The Seattle team looked at picture book examples before creating their own.

Photo courtesy of Seattle Public Library

Library as anchor

In New York State, 65 percent of the ELL students are native Spanish speakers, state data show. Librarians can tap a wealth of Spanish-language materials to cultivate their communication and language-acquisition skills. Bilingual books such as Growing Up with Tamales can serve as a bridge between the native and the target language for both students and their caregivers. But nearly 50,000 students in the state are native speakers of Chinese, Bengali, Russian, and Arabic, languages that are less common and more difficult to find.

“I think traditionally when people have moved to the U.S., they’ve looked to the library for guidance and help in assimilation,” says Kate Nafz, head of children’s services at the Maurice M. Pine Public Library in Fair Lawn, NJ. “The groups are changing a bit, and now we have a real gap in our materials.”

For example, the need for Arabic-language books has become pressing at her library, she says, as parents drive in with their children from nearby Paterson.

For example, the need for Arabic-language books has become pressing at her library, she says, as parents drive in with their children from nearby Paterson.

Librarians face multiple issues trying to serve the newer populations, according to Robbin Friedman, a children’s librarian at Chappaqua (NY) Library. First, “identifying decent materials in a language you don’t speak. Even when there are materials, we don’t necessarily know how great they are going to be.” Second, says Friedman, “when we have a small, even if growing, population, how to spend our book budget on them.”

The foreign-language books that librarians do have access to fail to sufficiently engage her high school ELLs, says Grace Dang of the Brooklyn (NY) International School. She describes their needs as “high-interest, low-level reading.”

“If we’re talking about complex topics such as gun control, or religion, or even recent issues such as the presidency, it would be good for the students to have it more accessible,” Dang says.

Nafz, who’s nearing 25 years at Fair Lawn, has amassed just shy of 15 shelves of foreign-language children’s books. Built largely from donations, her collection has a good showing of Russian, Spanish, and Hebrew books, and a small selection of books in Korean and Italian. She relies on parent volunteers to filter inappropriate titles from the collection, which can be used by the borough’s six elementary schools and Bergen County’s 77 libraries.

“I don’t have the collection organized in any specific way, because I couldn’t maintain that,” she says. “I just keep it neat.”

Kate Eads at Northgate Elementary School in Seattle doesn’t have a system for organizing or vetting materials—“that’s just me Googling,” she says. Her collection is built through contributions from others.

“I’m dependent on hand-me-downs and donations,” she says. Northgate did, however, receive a $10,000 donation, some of which Eads will spend on books in Cantonese and other languages represented in her student body.

If the sole goal was a child’s mastery of English, these native language materials wouldn’t be such a critical issue. But the materials are essential, Nafz believes, to engage and support caregivers and better serve the entire family.

“The kids are going to learn English; they’re surrounded by it,” Nafz says. “A grandparent sees Korean-language materials and she feels at home, and we definitely want to support those families.”

Fair Lawn offers Russian storytimes, echoing a trend seen across many libraries in the New York tristate area where there are Spanish storytimes and even one in Tagalog at the Bergenfield, NJ, library.

Students in Nafz’s district tend to get most of their reading materials from their individual classrooms. Field trips to the public library allow students to tap into its broader ELL collection.

“My lanyard says ‘read’ in all these different languages,” Nafz says. “Kids will look at it and they’ll get excited that they can identify their language on my person. A child will recognize a book in their language and jump up and down. It tells the kid, ‘This library’s yours.’ ”

Having books in a child’s or caregiver’s native language sends a message of inclusion, librarians say, of heightened importance at a time when the political climate has given rise to anti-immigrant sentiment and the U.S. Department of Education is considering dropping the federal Office of English Language Acquisition.

“This is a country where we speak English, not Spanish,” President Trump said on the campaign trail in 2015. “Whether people like it or not, that’s how we assimilate.”

The Trump administration’s rhetoric, its attempt at a travel ban on citizens of some Muslim-majority countries, and its “America First” doctrine have raised concerns among librarians that ELLs may shy away from asking for the help they need.

“I think within the new immigrant community, some people are very tentative approaching me about using the services of the library,” Nafz says. “I’ve seen it more with my Middle Eastern population—they kind of seem hesitant to say where they’re from.”

Robbin Friedman, a children’s librarian at Chappaqua (NY) Library, holds a book in Hindi that was written and self-published by a local father years ago and has since circulated throughout the county’s library system.

Photo courtesy of Chappaqua Library

But she and others across the country say that, if anything, the situation has made them more resolute about the need to nurture their ELL students.

“I’ve seen teachers and support staff really double down on their advocacy of the students,” says Kelly Matteri, an ELA teacher at the Sonoma County (CA) Office of Education. They know “that they’re kind of safeguarding that child’s educational experience.”

Tinkering to proficiency

One school of thought gaining momentum in the ELL-education space is the maker movement, with advocates saying children are more likely to develop and retain English if it has practical value for them.

“A lot of school is about delivery of content rather than creating experience,” says Dale Dougherty, a cofounder of O’Reilly Media who is now better known as the CEO of Maker Media. “If they focused more on creating experiences, they’d have greater buy-in from kids doing things. They’d be building their own sense of confidence and capability. What speed, for example, does my race car go at? And how can I measure it?”

Language acquisition “would be more on the applied side rather than the theoretical side,” he says. “The lesson judgement is less on, ‘How well did you understand something?’ and more on ‘Did you understand something well enough to do something and then replicate/improve it?’”

Educators say makerspaces can boost ELLs’ confidence and desire to speak English.

“A well-designed maker experiment really starts with that exploration: that people are interacting without a whole front-loading language that allows them to push past perceived barriers,” says Casey Shea, coordinator of maker education at the Sonoma County Office of Education.

During the maker sessions, ELLs “are being seen as valuable contributors to the academic conversations,” says Matteri. They can incorporate hand gestures and sound effects to participate. “It’s scaffolding in a really intentional and purposeful way.”

Grassroots success

The most promising initiatives seem to be ones that sprout up in one community and are noticed and implemented by other populations with similar needs.

Miriam Lang Budin worked in the children’s department at the Chappaqua Library before retiring in December. She recalls a Hindi-language book that was written and self-published by a father in the community. The book circulated throughout the Westchester Library System far more than she originally thought it would.

Baro Af-Soomaali already seems to be having an impact beyond its community. After the Seattle Housing Authority’s webinar on the project, representatives from the Minnesota Housing Authority reached out to discuss ways to contribute to future books.

At school, the book is having an impact on the wider student body. The Somali students “see themselves,” says Northgate’s Eads. “They get to see it in print. That alone is so affirming for any of us [who] have any kind of intersectionality.”

Eads says it also helped her native English speakers to see the connections between their language and that of their classmates. “ ‘That looks just like our alphabet,’ ” Eads recalls the children saying. “Then we got to talk about similarities and differences. We don’t all have to be apple pie and hot dogs.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!