Kwame Alexander: "My Purpose and Passion Is Creating Community" | The Newbery at 100

The Crossover author on growing up with poetry, winning the Newbery, and the five Black contemporary poets every young person should read.

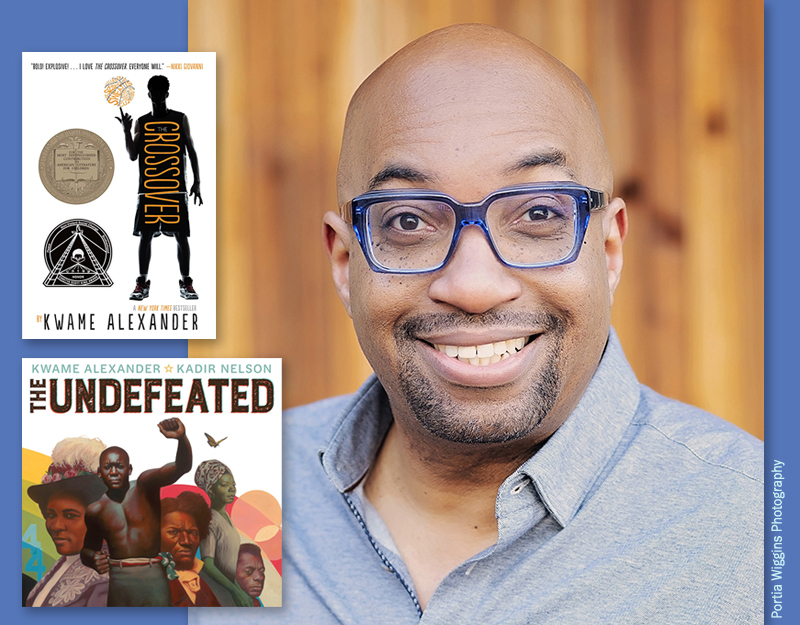

The Newbery Committee has recognized Kwame Alexander twice: He won the Newbery Medal in 2015 for The Crossover and capped it with a Newbery Honor for The Undefeated (both HMH) in 2020. His work has popularized poetry with a range of readers, while his centering of Black experiences and his commitment to building community has demonstrated the broader importance and impact of his work.

What are some of the ways in which your life changed after winning the Newbery for The Crossover (if it did)? Has winning the Medal and an Honor award made anything easier for you?

My career changed. Perhaps a week before I got that call about The Crossover, I was looking on different job sites. I’d been laid off probably about a year before. When The Crossover came out, I began to get a lot more interest in school visits. Prior to that, I’d done five to 10 [visits] per year. Afterwards, I began to get a lot more interest in visiting schools—five to 10 a month—and was able to charge a bit more.

The day I won the Newbery, I got a call from Lois Lowry and texts from Linda Sue Park and others who had won the Newbery with some sage advice. “Welcome to the club [they said], and here are the benefits of being in the club.” Linda Sue Park suggested, “If you strategize and play your cards right, you should not have to go back to looking for another job. Writing can become your job and provide you with the living you hoped it always would.”

Winning the Newbery allowed me to make a living and support my family in a way that was life giving and life saving. Secondly, it made The Crossover accessible to students around the world. When you write a book, you want a lot of people to read it. The Newbery enabled that. But it did put pressure on me in terms of what I was going to write next!

How does your success create opportunities for solidarity with other Black children’s authors and illustrators?

I’ve always been involved in writerly and literary pursuits. In college, I wrote and directed plays and employed lots of actors. I started a theater company and then a publishing company in Arlington, VA, to give voices to other actors and writers. I was trying to create opportunities for other artists to shine, and at the same time, I wanted to shine, too. It's great to be able to pursue your artistic dreams, but it’s also great to create and be a part of a community.

In 2005, I started The Capital Book Festival, [featuring] hundreds of writers each year. [For me], it was always about making sure there were venues that artists could shine in and through. [Those opportunities] weren’t there for me. I am because we are. That feeds me. I love writing. I love being able to create stories that are meaningful and significant, but my purpose and my passion is creating community. That’s always been in my DNA.

Audre Lorde said that for Black women, “...poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence….Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” For you, and from where you sit, what is the meaning of poetry and the importance of it for Black children and other readers?

Poetry is the language that my parents introduced me to at a very young age: Lucille Clifton’s poetry, Nikki Giovanni’s Spin a Soft Black Song; [Shel] Silverstein; [Dr.] Seuss; Langston Hughes. I didn’t grow up thinking of poetry as outside, other, or special. It just was.

I found that I was attracted to the concise language, rhythm, wit, and the heaviness of topics from the Black Arts poets in my father’s library: Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, [Haki R.] Madhubuti, [Amiri] Baraka. Short poems that hit you hard.

The poetry was the thing: funny, truthful. It was edgy; it was so much white space. It became the way that I learned to appreciate literature. It was my entry point, and I’ve loved it ever since. It gave me voice, and it built my confidence as a writer and a reader, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I hope it does that for my readers, and readers of poetry in general.

Who are five contemporary Black poets every teenager should read?

Nikki Giovanni, Terrance Hayes, Jericho Brown. Nikki Grimes is an amazing poet; two books in particular I would recommend are One Last Word: Wisdom from the Harlem Renaissance, and her memoir, Ordinary Hazards. Ashley Woodfolk has a novel in verse coming out, Nothing Burns As Bright As You; you forget that you’re reading poetry.

What would you tell teachers and families who might want to teach some of your books but are worried about backlash?

Look at the gold sticker on the front of The Crossover. Look at the gold sticker!

Trust librarians.

You gotta be bold. You’ve got to be brave if you want our children to be better than we were and are. The mind of an adult begins in the imagination of a child. We want them to be wild, expansive, and full of every possibility that exists in this world and that they’re exposed to as much as possible.

What’s next for you?

The Door of No Return (Sept. 2022, Little, Brown), the first book in a trilogy. I cannot wait for readers to go on that journey. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever written. It’s the saga of an African family told through the eyes of a 12-year-old boy. I’m sick of people writing about the middle of our story as if that’s the beginning. We all are familiar with the American part of African Americans, but we ain't as up on the African part. My job is to tell that story.

Dr. Kimberly N. Parker is the Director of Crimson Summer Academy at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!