Is There a Looming 'Dog-Man' Crisis? | Soapbox

Censorship is delaying the delivery of books to school library shelves. Cue the civics lesson.

|

Books left: Alisa Zahoruiko/Getty Image; right: TopVectors/Getty Images |

Between the passage of an anti-librarian law in my home state of Texas and local school districts’ creation of bureaucratic book-purchasing hoops for their media specialists to jump through, it’s becoming ridiculously difficult in some places for newly published books to make their way onto library shelves in a timely fashion.

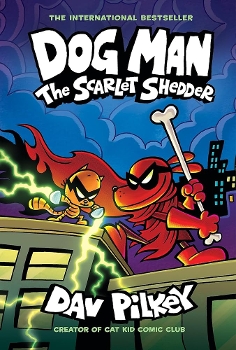

Sounds bad enough in abstract. So what would happen if the 12th book in Dav Pilkey’s phenomenally popular “Dog Man” graphic novel series, out in March, isn’t available for library checkout right away?

Disappointment? Sure. Frustration? You bet. But how about, also, a kid-level civics lesson in the politics that led to that delay?

I don’t know how aware most parents and guardians are of attempts to ban books from their kids’ schools. There’s a lot else vying for their attention, and so much good stuff on TV.

I suspect that they’d take more notice if the kids themselves could see the role that their family members’ voting (or lack thereof) has played into how their school libraries work—or don’t.

If Dog Man #12: The Scarlet Shedder is delayed, that might provide the perfect opportunity for librarians and their classroom allies to launch a kid-level conversation about civics.

“Hey, kids! The good news is, there’s a new ‘Dog Man’ out today!”

[Students’ wild cheering eventually dies down.]

“The bad news is, we won’t be able to have it in the library until sometime next school year.”

[Stunned silence ensues.]

“But wouldn’t Dog Man and Cat Kid want us to get to the bottom of this problem?”

It’s not that there’s anything wrong with the “Dog Man” books themselves.

As a visiting author, I’ve seen firsthand the carts full of unobjectionable school library books, selected and purchased well before publication, that didn’t yet make it to the shelves. That’s because new policies are gumming up the works in order to appease reactionary school board members or meddlesome locals who insist they know what’s best for other people’s families.

A book distributor told me that some of its library customers have been forbidden by their district from buying titles that the librarians haven’t personally read. But reading each individual title is impractical even after the books are published, let alone before.

A book distributor told me that some of its library customers have been forbidden by their district from buying titles that the librarians haven’t personally read. But reading each individual title is impractical even after the books are published, let alone before.

These may sound like grown-up problems that most kids would be happy not to consider. But what if those grown-up problems come between kids and the latest book by Pilkey…or Jeff Kinney, Tui T. Sutherland, Suzanne Collins, or Rick Riordan?

Educators can use such possible scenarios to help students understand how decisions made by their own families may have affected their librarian’s ability to get those highly anticipated new titles into circulation.

If nothing else, at least this crummy and entirely unnecessary assault on librarianship can be used to teach students about the importance of participating in our political system and how that system personally affects them.

And though the legislation and policies in question are partisan—they sure aren’t coming from the Democrats—the conversations around them need not be:

“Why does it matter whom people vote for?”

“When someone wins an election, what does that person get to decide?”

“Let’s look at just one decision made by elected officials and see how that decision—and those votes—affected you as a reader right here in this school.”

Take Texas, for instance, where nearly every state legislator has gone on record with votes for or against the law variously known as House Bill 900, the READER Act, and (in a federal lawsuit) the Book Ban.

I began compiling updates about the legislation last spring and started a new roundup in September after U.S. District Judge Alan Albright found that “this law violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”

The law severely limits which vendors school librarians can purchase books from—you know, because of “porn.” Regardless of how the lawsuit plays out, it has inspired further hassles at the local level.

Every public school’s attendance zone is in the district of at least one state representative and one state senator. How did those House members and Senate members vote on that legislation? It’s worth exploring that with students.

In other words, did the legislators who represent those students’ families vote to make it harder to get the new “Dog Man” onto shelves when it’s published?

And who elected those lawmakers? It would be easy for educators to illustrate for students each legislator’s margin of victory in their most recent election. Some basic math could show how many additional votes in one direction or the other would have changed the outcome of the election.

That is, how many voters making a different choice at the polls might have resulted in a different vote on behalf of constituents—including students—on whether to pass HB 900/the READER Act/the Texas book ban? That’s not hard for even elementary students to grasp.

Now, maybe students know which candidates their parents or guardians voted for last time, or maybe they don’t. Either way, that is more of an at-home discussion, not a school one.

However, it’s quite possible that students’ adult family members didn’t vote in those races at all.

Seeing how many registered voters in those legislators’ districts didn’t vote, and how many people eligible to vote were not registered—data that can be researched in the school library!—could make it easy for students to see the effect that choosing not to vote can have.

The overriding lesson—how the voting decision made by a student’s parent or guardian can indirectly affect the ability to quickly get exciting new books onto library shelves—would be a great one to relay to the folks at home.

I suspect that the number of families who would welcome this assistance—perhaps in the form of an inarguably just-the-facts handout or email—in helping their children become active, informed citizens would far outnumber those who would object, since we already know that it’s a tiny minority that is challenging books or pushing for bans in the first place.

But these conversations at school and home shouldn’t focus only on the past. Looking ahead, who are the candidates in the 2024 elections for legislative districts that include that school’s community?

Where do those candidates stand on HB 900/the READER Act/the Texas book ban, and why?

What would students want their parents or guardians to know about the importance of being registered for and casting ballots in the 2024 elections?

Hint: It might involve Dog Man #13.

Chris Barton’s picture books include the best-seller Shark vs. Train and Whoosh! Lonnie Johnson’s Super-Soaking Stream of Inventions.

Chris Barton’s picture books include the best-seller Shark vs. Train and Whoosh! Lonnie Johnson’s Super-Soaking Stream of Inventions.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!