How “El Deafo” Empowers Kids Who Are Deaf and Hard of Hearing

El Deafo fan Sarah Thibodeaux found strength in the book and her meeting with Bell. Photos courtesy of Kathleen Thibodeaux

Sometimes, kids give Cece Bell little notes: “I’m deaf like you.” Other times, if a child is wearing a hearing aid, “It’s just an act of taking it out, or showing it to me,” says Bell. Or they hold up their devices and cheer: “Look! Yay!” “It’s kind of a magical moment,” says Bell, the best-selling author of El Deafo (Abrams, 2014), her graphic memoir about a young girl who loses her hearing—and finds strength and resilience by conjuring an alter-ego deaf superhero named El Deafo. When kids who are Deaf or hard of hearing (HoH) meet Bell, “we’re on the same team; everybody else gets blocked out,” she says. “I really enjoy when it happens.” El Deafo follows young Cece through the travails of volatile friendships, frustrating and sometimes comic misunderstandings, self-advocacy, and empowerment. Embarrassed at school by her bulky Phonic Ear hearing aid, which she hides under bib overalls and uses while also reading lips, little Cece turns the device from albatross into asset: the Phonic Ear can tune into conversations in other rooms, prompting her imagine to herself as El Deafo, complete with a red cape. The book, in which all characters are portrayed as rabbits, won a Newbery Honor in 2015—the first graphic novel to be recognized by the Newbery committee. Bell’s many other titles include the “Rabbit & Robot” books (Candlewick) and the “Inspector Flytrap” series (Abrams), the latter written with her husband, Tom Angleberger.

Elementary students from the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf (AASD) and two local schools participate in a reading and a book club about El Deafo at the Little Shop of Stories Bookstore in Decatur, GA, with an ASL interpreter. Photos courtesy of Amanda Lee

Since its publication, El Deafo’s story of resilience, with an endearing dose of humor, has had particular resonance for students and educators in the Deaf and HoH community. Bell “was a rock star” when she visited the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf, says Amanda Lee, the school’s media specialist. Dee Castillo, who works with HoH students from Fairfax County (VA) Public Schools, adds that Bell is “one of those real role models” for HoH children who haven’t met many adults like them. El Deafo has been a game changer for educators too. “The book has helped me personally and professionally better understand the students I work with,” says Pamela Sperry, teacher of the deaf and HoH at Loudoun County (VA) Schools.“Just like me!”

Marie DeBrodt, who teaches integrative services to students at Richmond (VA) Public Schools, gave El Deafo to Sarah Thibodeaux, who was in kindergarten ad the time and uses a hearing device similar to Cece’s, “albeit the digital-age version,” DeBrodt says. Though the book was beyond Sarah’s reading level, she assiduously “read” it and invented stories to go with the pictures. “She would point to the pictures and say, ‘Just like me!’ The surprise on her face spoke volumes,” says DeBrodt. The speech bubbles in El Deafo are often blank or contain garbled words to convey the protagonist’s hearing experience, which kids like Sarah also connect with.

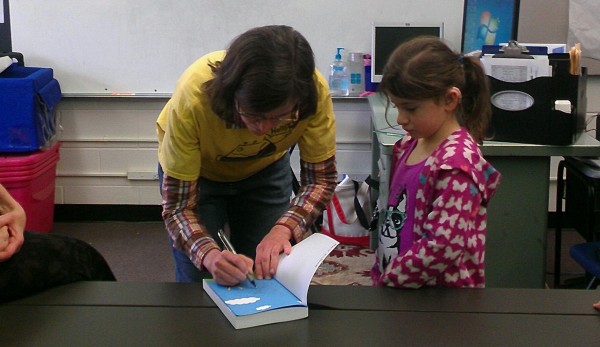

Bell signs a book for Sarah Thibodeaux.

When Bell came to speak at Sarah’s school and chatted with her while autographing a book, “it may have been Sarah’s first encounter, up close and personal, with a deaf person who conversed with her,” says DeBrodt. Sarah still tells DeBrodt how she “reads” the book before bed or while in the car. “I know she is not literally reading the words,” DeBrodt says. “She is comforted and edified by the kinship she feels with the character.” While writing the book, Bell was nervous about how it would be viewed by those in the Deaf community who use American Sign Language (ASL). El Deafo’s Cece attends a mainstream school and refuses to learn ASL, at one point kicking her mother in fury during an ASL class. Fearing that this aspect of the book would receive a hostile reception, “I would go to bed hot, thinking, ‘I can’t release this book. I can’t do it!’” Bell says. “A few times, I almost backed out. But I’m glad I have that chapter in the book, because it’s honest.” Plus, “Even though I don’t sign, we have a lot of the same problems.” Her worries were unfounded. Amanda Lee, library media specialist at the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf, has given the book to kids who have a wide range of hearing loss. “We teach English, but our main language is ASL,” Lee says. “I was curious how kids would respond to it. I had only one or two who said, ‘that’s not me.’ The rest didn’t care. It was a deaf person who has struggles like [the kids here have]. So much is universal to their experience.”

Bell demonstrates her technique onstage during an event the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf.

“It inspired them to be who they are, and that’s really the central message,” adds Lee. After her students had a Skype visit with Bell, “I could not keep copies of the book on the shelf,” she says. “A high school girl who refused to return the book to the library. She finally told me that she loved the book so much that she wanted to keep it, because she had never seen a book with a character like her before.” Lee later bought the girl her own copy. When a local bookstore, Little Shop of Stories in Decatur, GA, hosted a reading event with the book, “I knew we had to be involved,” she says. “Our kids saw hearing kids read the book and connecting on the same topic....The hearing kids got to meet our kids and share experiences.” Later, when students from another school were researching a project about disabilities, they interviewed Lee’s students via Skype.Teaching empowerment

There’s a pivotal scene in El Deafo in which the classroom teacher leaves the room to use the bathroom while still wearing the microphone that amplifies sound for Cece’s Phonic Ear. Asked what Deaf and HoH kids relate to most about the book, Bell says, “the kids are most excited to share the fact that they’ve also heard the teacher in the bathroom. I think it’s fun having that power,” she notes. “You know, ‘I can hear you in your most vulnerable moment.’” That resonates with Stephanie Chris’s students. “All of them have somewhat similar FM systems. They like the whole idea that she could hear through walls,” says Chris, an itinerant teacher for students who are Deaf/HoH whose base school is Alvey Elementary school in Haymarket, VA. Educators say that the book’s strongest message for kids who are deaf or HoH is about empowerment and self-advocacy. El Deafo’s heroine “has gone through what my kids have gone through,” says Sperry, who adds that all of her students speak while also using a “whole gamut of electronics” to assist them.

Fifth graders at the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf participate in a virtual book group with students from the Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School.

Sperry finds many teachable moments in the book. In one scene, Cece is at a slumber party. When the lights go off and she can no longer read lips, she is lost. Reading this with her students, Sperry will ask, “‘Has this ever happened to you?’’” she says. “I will usually brainstorm: ‘What can help you in that situation?’” Sperry also focuses on the speech bubbles. “We talk a lot about the blank ones, where she can’t hear. We say, ‘what’s happening here?” Sperry occasionally asks her students, some of whom lag verbally, to read the book aloud. When one of her fourth graders does so, “It’s a great way for me to listen to his articulation,” she says. Chris also uses El Deafo with students “to bring out how it relates to what they’ve gone through,” she says. “For some of them, I know parts of their lives are similar: aspects like feeling different; like they don’t have friends; or like everybody’s yelling and they don’t understand.” Bell says that frequently, hearing kids approach her and say, "‘Man! Where can I get one of those hearing aids?’ They actually want one! I say, ‘No you don’t! You don’t want one, and you don’t want to have to use one.’ But they get really excited about the technology and want to try it out.” Her favorite response to the book was from a “super fan” in the fourth or fifth grade. “She got the book at exactly the right time,” Bell notes, adding that the girl had a few copies—one that her family bought and one that Bell sent to her. “She needed to get hearing aids, and she was scared.” El Deafo includes a scene in which Cece is fitted for hearing aids. “So she saw [that] and thought, ‘Oh, it’s probably going to be OK.’” “The next time she went to the audiologist’s office, a little boy was there,” Bell adds. “He needed to get hearing aids, and he was scared, and he was crying. She gave one of her copies to him. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh. She is so young, and so giving.’ That just blew me away.” The “super fan,” Bell adds, wears bibbed overalls, like young Cece in the book. She even visited Bell’s childhood home in Virginia and took a picture of herself in front of it, wearing the overalls.“Here’s what it’s really like”

Growing up, Bell was drawn to books with strong female characters. “I liked the ‘Ramona’ series by Beverly Cleary,” Bell says. “That was my all-time favorite. I liked Judy Blume, and The Secret Garden was way up there.” In terms of picture books, “my favorite is Our Animal Friends at Maple Hill Farm by Alice and Martin Provensen [Random House, 1974],’ she adds. “Caddie Woodlawn was another one, and the ‘Little House’ books…They were kids who were flawed but strong, and they persevered.”

Bell, with an ASL interpreter, answers a student's question at the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf.

“I wanted to be like them, because I didn’t see myself as strong,” she adds. “I struggled to speak up for myself and I thought, ‘Boy, maybe if I read one of these, I’ll be like Caddie Woodlawn and speak my mind and kill a bear. That’s what I was looking for in my book.” However, when she was a kid, “I never saw a book with a deaf character I related to,” Bell notes. Most were “angelically good—and like a blank slate who can’t hear.” “I am grateful when anyone puts a deaf character in a book,” she adds. But “most of them are not written or presented by deaf people. That may be where I have an edge. . . . I know it backwards and forwards.” One book she does like is Brian Selznick’s Wonderstruck (Scholastic, 2011), starring deaf protagonists Ben and Rose. “Wonderstruck is fantastic,” says Bell. “Rose is a great character, and a real person.” “My book, in a way, is for hearing people: ‘Here’s what it’s really like, here are some pointers,’” Bell says. Originally, she conceived it as a kind of manual about her deafness: “‘Here’s what lip reading is like,’ and ‘here’s why I don’t use sign language,’ and ‘here’s how I lost my hearing.’” There wasn’t much about school, or relationships with other kids. “It had maybe one friend.” At the urging of her editor, Susan Van Metre, the book quickly evolved. “Susan said, ‘Oh, no, we need more of this friend stuff. What was going on in school? Come on!’” She also took inspiration from Smile (Graphix, 2010), Raina Telgemeier’s graphic memoir about surviving traumatic dental surgery when she was a girl. For a time, Bell was writing a blog about her hearing loss. “I was really frustrated; it was a rough time,” she says. “Around then, I read Smile. I thought, ‘Oh wow, this is it! This is how it can be done.’” She and Telgemeier are now good friends. El Deafo has been life-changing for Bell as well. Now, at American Library Association meetings and other events, “There’s always a teacher or librarian hidden away with hearing aids. And then they approach me, and we’re instant friends.” “It’s been very empowering,” Bell adds. “I put a book out there that said, ‘I’m deaf,’ and that’s something I couldn’t say for many, many years—the majority of my life. During my childhood and adulthood, I could not say those words. And now I’m saying them, and it’s no big deal.”RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy: