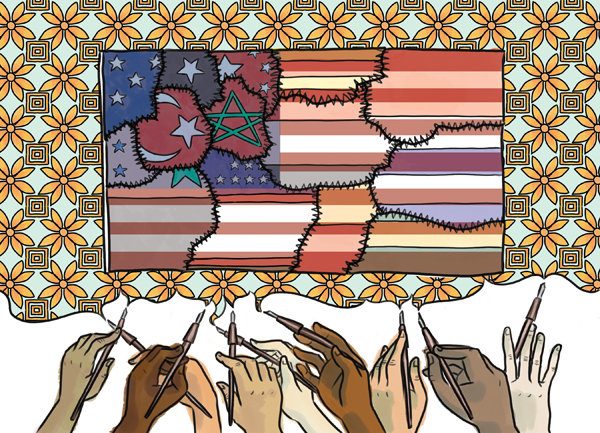

Graphic Novels Portray Bicultural America

Illustration by Marguerite Dabaie

Superman, arguably the most iconic figure in the history of comics, is a champion of “truth, justice, and the American way,” in the words of the 1940s radio show “Adventures of Superman.”

He’s also an immigrant. A refugee, in fact, sent off by his parents to escape their dying planet Krypton and make a better life for himself on Earth. His creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were themselves the children of Jewish immigrants. “Superman was the ultimate assimilationist fantasy,” said their fellow cartoonist Jules Feiffer in an interview for Danny Fingeroth’s book Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero (Continuum, 2007).

“The mild manners and glasses that signified a class of nerdy Clark Kents was, in no way, our real truth. Underneath the schmucky façade there lived Men of Steel! Jerry Siegel’s accomplishment was to chronicle the smart Jewish boy’s American dream,” Feiffer believes. “It wasn’t Krypton that Superman came from; it was the planet Minsk or Lodz or Vilna or Warsaw.”

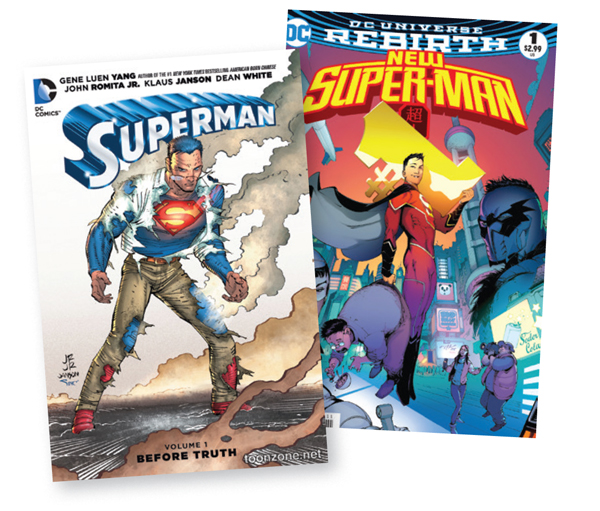

Yang’s Superman and Super-Man,

the latter starring a Chinese superhero

Courtesy of DC Entertainment

“Superman navigates two different identities,” notes graphic novelist Gene Luen Yang, the U.S. National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, who is the son of immigrants from China and Taiwan. “He has two names, Clark Kent and Kal-El. He has two outfits, an American one he wears to work, and a colorful foreign one he wears for special occasions.” The superhero has special resonance for Yang, who wrote four issues of the Superman comic last year, collected in Superman, vol. 1: Before Truth (DC Comics, 2016). “He lives under two sets of expectations,” Yang says. “I was the same when I was a kid. I had a Chinese name at home, an American name at school. I spoke two languages and lived under two sets of expectations.” Yang is also writing a different superhero story for DC, Super-Man, featuring a Chinese superman and set in China.

Amid U.S. election-year rhetoric and global discussions focused on immigration, graphic novels by Yang and many others offer other windows onto this topic—by telling their stories about being bicultural Americans who have immigrant parents. The most powerful graphic novels on this subject invite readers to walk alongside protagonists as they face the problems and conflicts associated with negotiating two cultures. The visual medium is particularly powerful, as it easily conveys details of home life, dress, and gesture without excessive description. The format also allows creators to portray subtle nuances—a side glance, a change in posture—without interrupting the narrative.

Yang wrote about his own experiences in American Born Chinese (First Second, 2006), which won an Eisner and a Printz award and was a finalist for a National Book Award. His story was a touchstone for other graphic novelists. “It vibrated through me like a tuning fork,” said Vera Brosgol, the daughter of Russian immigrants and the author of Anya’s Ghost (First Second, 2011). “I’d never encountered that shame of one’s heritage outside of my own head, and it made me feel connected, understood, maybe even forgiven. I was so grateful to Gene for exploring such a sensitive subject, and I started to think that my own unpleasant feelings would be worth writing about if there were any chance they’d connect with a reader.”

Nidhi Chanani’s Pashmina

Courtesy of First Second Books

Living in two worlds

Many of these creators were born in the U.S. to foreign-born parents. To outsiders, they are the foreigners; to their families, everyone else is a foreigner. “I grew up here!” says 16-year-old Kamala Khan, the daughter of Pakistani immigrants and the current star of the popular Ms. Marvel comic. “I’m from Jersey City, not Karachi!”

Ms. Marvel creators G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona portray Kamala’s frustrations with her parents: she complains about having pakoras for lunch and being stuck with the “weird holidays.” But when she sneaks out to a party, she quickly realizes that blending in with the other kids is not that simple. “Zoe thought that because I snuck out, it was okay for her to make fun of my family,” she says. “Like, ‘Kamala’s finally seen the light and kicked the dumb inferior brown people and their rules to the curb.’”

Nidhi Chanani addresses these same kinds of conflict in her graphic novel Pashmina, a fantasy about an Indian-American girl connecting with her heritage, which will be published by First Second in 2017. “Growing up with a dual identity has disadvantages, because as an adolescent you are simply trying to fit in,” says Chanani. “However, without a core understanding of what would enable that, which comes from being privy to cultural norms through your family, your struggles are multiplied.”

“Everyone has to figure out who they are as they grow up, but there’s extra work for the children of immigrants, because we have at least two cultures to contend with,” says Yang. “We have to figure out how these cultures speak to each other, where they contradict, and how they might fit together.”

In Keshni Kashyap and Mari Araki’s Tina’s Mouth: An Existential Comic Diary (HMH, 2012), for instance, 15-year-old Indian American Tina casts a sharp eye on the social structure and drama of her high school and her family, dealing with the usual pitfalls of boys, cliques, and fair-weather friends and casting an equally cold eye on her Indian relatives—and outsiders who project images of India onto her.

For some creators, the conflicts are dramatic. Dan Santat’s You Bad Son, to be published by First Second in 2018, is a memoir of his high school senior year. “As the only child of Asian parents who had immigrated from Thailand, “my entire life up to that point was steered in the path of becoming a doctor,” says Santat, whose book The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend (Little, Brown, 2014) won a Caldecott Medal. Santat “[pursued] my passion of art and secretly took art classes to apply to art school without my parents’ knowledge. All of this happened while my mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer, which caused my father and I to butt heads often during her chemotherapy. He couldn’t care for her because of his inability—or perhaps an unwillingness because of his traditional Asian male upbringing—to cook or clean, which left me with many feelings of resentment.”

Santat’s forthcoming You Bad Son

Courtesy of First Second Books

You’re not welcome here

In addition to family issues, second-generation immigrants often must contend with prejudice and stereotypes from their peers. “Many of the ‘culturally insensitive’ taunts I put in American Born Chinese I heard in the halls of my junior high,” says Yang. In Ms. Marvel, a high school peer quizzes Kamala’s friend about her veil: “Nobody pressured you to start wearing it, right? Your father or somebody? Nobody’s going to, like, honor kill you?”

Marguerite Dabaie’s self-published comic The Hookah Girl is a series of short comics about her upbringing as a Palestinian American Christian, a heritage that she didn’t give much thought to as a child. “I had spent my childhood first not realizing how truly politicized Palestinians are to most Americans, then not discussing my complicated thoughts on the orientalization, gendering, and politicization of Arabness,” she says. “Following September 11, so much hatred was swirling around. I felt very viscerally that I couldn’t feign ignorance anymore, and I started getting in touch with this aspect of my life I had neglected. The Hookah Girl ended up being like a ‘coming out’ book for me, where I really got to say, ‘Yep, I’m Palestinian.’”

In her self-published comic Gringa!, Kat Fajardo depicts the hostility she encounters from people who assume she is Mexican (she’s not) and a noncitizen (she was born in the United States). “As a second-generation kid, why did I have to feel shame over my own family’s background?” she writes in Gringa! “Or the fact that they risked their lives and used their life savings to travel up north due to poverty and vicious gang activities. If anything, I should have proudly worn my heritage like a medallion on my chest.” Instead, she balks at the Latina side of her heritage and tries to pass for white—until a younger cousin helps her see the folly of that.

You can’t go home again—or can you?

While Fajardo chose to embrace her heritage, others find that returning to their roots can be a challenge, as Brosgol chronicles in her next book. Be Prepared, (First Second, 2018) is about her experiences at a Russian Orthodox summer camp in upstate New York when she was nine. “Hoping to find easy acceptance, I convince my mother to send me to the camp, where I’m met with more challenges than I ever expected,” she says.

Even coming back to the old neighborhood can be an emotional event. In her self-published comic Phantom, Aatmaja Pandya writes warmly about her childhood neighborhood in Queens, NY—the most diverse city in the world, she notes—and her ambivalence about its changing demographics. “Queens is for immigrants and families—why would anyone just out of art school move here?” she asks. “It was like my secret hideout was being broken into….Here, I can feel my roots more strongly than I ever could anywhere else, even back in India….I’m afraid the day I don’t feel this place in my bones is coming too soon. Then where will I go back to?”

Marguerite Dabaie’s Hookah Girl

Panel courtesy of Marguerite Dabaie

A natural format

Many creators are drawn to how the visual aspect of the graphic novel medium enriches their narratives. “My story has a lot of awkwardness, and not all awkwardness is verbal,” says Brosgol. “I want the reader to feel for my protagonist, and being able to see her eyes when she’s going through something is so effective. I have big stretches with no text at all; those are the biggest treat to draw because it’s pure acting. I also love comics’ breezy ability to show physical humor—it’s much funnier to see someone falling in a ditch than to read a laborious description.”

For Yang, the magic comes from the combination of words and pictures. “The interplay between the two can be wonderfully sophisticated,” he says. “Also, each culture has its own way of communicating visually, its own iconography. It’s like a ready-made toolbox for a graphic novelist who wants to tell a culturally specific story.”

“Through panels, composition, staging, acting and color there are storytelling benefits to comics that are very different than prose,” says Chanani. “I enjoy the ability to tell a story in a nontraditional form.”

Gringa! by Kat Fajardo

Panel courtesy of Kat Fajardo

While their focus is culturally specific, these stories also have something to offer to anyone who has felt like a stranger. Dabaie says that her work resonates with people who grew up in households that don’t strictly follow “traditional” American customs. “I think a lot of people especially relate to the stories about my grandmother because her actions were specific but universal in a lot of ways,” she says. “She was totally into spraying WD-40 on her hands to help with her arthritis—so many families have at least one relative with eccentric home remedies. She’d go and trespass on some vineyards so that we’d have fresh grape leaves for waraq diwali [stuffed grape leaves] because we had no other way to obtain fresh leaves, and the canned leaves are blah by comparison. That love for food, and that need to make it absolutely right, is extremely universal.”

Santat also sees a universal aspect to his own struggles. “While working on my own story, I’ve gone through a lot of personal healing,” he says. “As an author, I have to write an honest voice of my parents without sounding one-sided or biased….It’s a tough moment as a kid when you realize your parents aren’t perfect people, and I think it’s a feeling most kids can identify with.”

Santat says he felt that American Born Chinese was written specifically for him; like Brosgol, he had an instant connection. “[It] showed me that I wasn’t alone in my feelings of anger and frustration while growing up as the child of Asian immigrants,” he says. “The book changed my life.” Back to the top.

Suggested Reading

BROSGOL, Vera. Anya’s Ghost (First Second, 2011) Gr. 7 Up —Anya has the usual teenage hatred for her family, including her Russian-born mother who has high expectations and serves up high-calorie treats. When she meets a ghost with supernatural powers, Anya realizes how much her family means to her. A 2012 Eisner Award winner.

DABAIE, Marguerite. The Hookah Girl (self-published, 2007) Gr. 10 Up —The daughter of Palestinian Christian immigrants, Dabaie muses about the image outsiders have of Palestinians and the quirks of her own family in a series of short comics.

FAJARDO, Kat. Gringa (self-published, 2015) Gr. 9 Up —Fajardo depicts the tension between her Latina heritage and her desire to fit in with her non-Latinx peers.

PANDYA, Aatmaja. Phantom (self-published, 2015) Gr. 7 Up —Pandya has mixed feelings when she returns to the very diverse neighborhood in Queens where she grew up.

TAN, Shaun. The Arrival (Scholastic/Arthur A. Levine, 2007) Gr. 7 Up —This classic depicts the experiences of a man who leaves his family and travels to a strange land. Tan creates a magical world whose alphabet and language, technology, and animals are realistic but not real, so readers feel as disoriented as the immigrant.

TRAN, G.B. Vietnamerica: A Family’s Journey (Villard. 2011) Gr. 11 Up —Tran accompanies his parents to Vietnam, which they fled at the end of the Vietnam War, and learns the history of his parents, their families, and what they endured. Using distinctive palettes, Tran moves between two story lines about each parent’s family. Nominated for an Eisner Award.

WILSON, G. Willow. Ms. Marvel, vol. 1: No Normal . illus. by Adrian Alphona. (Marvel, 2014) Gr. 7 Up —Kamala Khan is a 16-year-old comics nerd, the daughter of Pakistani immigrants, growing up in Jersey City. She has a nice set of friends who “get” her—while others don’t. Her problems get more intense when she becomes a superhero begins to shapeshift.

YANG, Gene Luen. American Born Chinese. (First Second, 2007) Gr. 7 Up —Yang weaves together three stories about the Monkey King, a high school student, and a caricature of offensive Chinese stereotypes, to create a tale of individuals just trying to fit in.

YANG, Gene Luen. Level Up. illus. by Thien Pham (First Second, 2011) Gr. 7 Up —Dennis Ouyang’s parents want him to become a doctor, but he finds success on the professional video game circuit. When angels suddenly appear and lead him back to medical school, Dennis gains new insight into his father’s life.

YANG, Gene Luen. The Shadow Hero. illus. Sonny Liew (First Second. 2014) Gr. 7 Up —The son of Chinese immigrants is pressured by his mother into becoming a superhero—and learns that upholding truth and justice is serious business, especially when his family is involved. Loosely based on the Green Turtle, created by Chu F. Hing in the 1940s.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!