Farewell, Fines: Libraries Eliminate Late Fees

Fines bar kids from library services, don’t bring in much revenue, and force staffers to spend time on bookkeeping. Several librarians say the pandemic was the catalyst for ditching them.

|

Self-checkout at the St. Charles City-County Library in in St. Peters, MOPhoto courtesy of Maggie Melson |

Late fines keep kids from accessing library services, don’t bring in much revenue, and force staffers to spend extra time on bookkeeping, according to many of the 100-plus school and public librarians who responded to an instant poll by SLJ. Several cited the pandemic as the catalyst for ditching fines.

Fines for overdue books and materials are a particular hardship for lower-income families, and students are more likely to stop using the library than to pay the fines. In general, public librarians expressed more concern about lost revenue than school librarians, though some public librarians say the revenue wasn’t worth the work it took to collect. Community goodwill was more important, many said; circulation increased after fines were nixed.

Moreover, students had enough to worry about during the pandemic without having to pay late fines.

Of the 115 responses to the September survey, 60.9 percent were school librarians and 39.1 percent were public. Of all respondents, 81.9 percent had eliminated fines and 18.1 percent had not.

Librarians cited the financial hurdle posed by charging fines. “Our community has a lot of kids on free or reduced meals at school. We felt this is just another way to offer library services without the patrons worrying about fines or fees,” wrote one respondent.

“Lower-income students were often afraid to check out books due to a fear of accruing fines if they forgot to return them on time,” wrote another. “Students were sometimes afraid to even enter the library. We wanted to focus on making the space as welcoming and inviting as possible.”

“Fines felt punitive, and they weren’t always the fault of the student,” one librarian wrote. “Our students often didn’t have the extra money to pay fines that accumulated over four years and had to be paid to receive diplomas.”

Helping seniors was also a concern for Breana Kambs, librarian/media specialist at Fairfield Jr./Sr. High School in Goshen, IN. She handles senior checkout at the end of the year, signing off so students can graduate. Seniors used to be charged 10 cents per overdue book per day. “Some graduated with over $100 in fines,” she wrote.

Melinda Thompson, media specialist at Wapahani High School and Selma Middle School in Selma, IN, says charging fines didn’t fit with the welcoming atmosphere she fosters. The previous librarian “would walk around the classes trying to collect the fines from kids.” Students would avoid both the librarian and the library. “I just felt like the fines create a barrier—we want to get books in kids’ hands,” Thompson says.

Now, she’ll let them know at the end of a grading period or year if they still have a book out. “Nine times out of 10, it’s in their locker.” While books aren’t necessarily returned more quickly without fines, that’s not her priority: “I just want them to read it.”

Fines don’t spur people to return books, says Maggie Melson, director of youth services at St. Charles City-County Library in St. Peters, MO. Instead, the embarrassment of being charged a fine pushes patrons away.

Melson says library staff wanted to drop the fines for a while, recognizing that “families that need the library the most tend to get hit the hardest.” Only about 14 percent of her library’s cardholders had fines. Of those, a disproportionate number were children and teenagers, who don’t always have the flexibility to return things promptly.

|

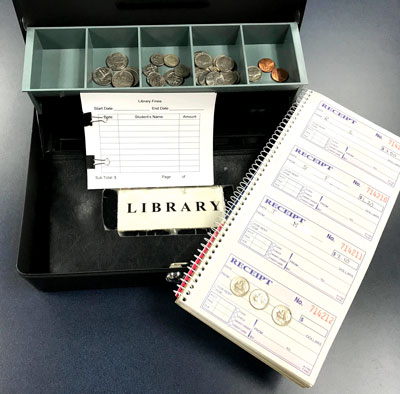

Money lost, time saved

Many librarians are relieved to stop hunting down fees from students and patrons. “It freed up my administrative time to work on making the library better, instead of shaking down second graders for pennies, and resulted in a more conversational, less adversarial relationship with my students and their families,” a respondent wrote.

Kambs is glad she doesn’t have to spend time trying to collect money, or adding up fees while checking out books.

Fines didn’t prevent books from disappearing, she adds. Sometimes students secretly take a book so it isn’t on their account. Juniors take ones they’re not allowed to check out without parent permission.

“I feel better about what I offer the students when I don’t have to nickel and dime them for every day that is late,” Kambs says. As for destroyed books, she says she’ll ask the family to replace the book if they can. With fines gone, she says, more students are being responsible about renewing books.

If a student loses a book, Thompson asks them to find a used copy of the same title to replace it. Families often donate other books as well when they replace a title. It’s a win-win for everyone, she says.

Jessica Little, director of the T.A. Cutler Memorial Library in St. Louis, MO, says her library dropped fines in January 2019, after realizing the amount of time they were spending on tracking down late fees wasn’t worth the small amount of revenue the fees brought in. The library didn’t publicize the change, so parents only found out by asking how much they owed. “There was some relief. There were some people that argued with us: ‘Well, you have to collect fines. I’m late!’”

Little says the library still contacts patrons to let them know something is overdue and has instituted automatic renewals. But the main goal of the change was to eliminate the time they spent talking to patrons about fines and collecting money. It encourages people to return books, where they might have felt discouraged before because of the fines, she says.

Previously, if a large family took out 30 books and brought them back a day late, they already had a $3 fine, “which I thought was ridiculous.” The staff would often manually waive the fees. Each transaction didn’t take much time, but it all added up, Little says.

Melson says fines had generated $200,000 for her public library during fiscal year 2020. But, she points out, that’s one percent of the library’s total $20 million budget. “In the grand scheme of things, it wasn’t that much.”

The solution she and staff came up with was to replace revenue by expanding passport services.

No matter the financial impact, Melson is happy about the time and effort saved. Previously, library staff spent a lot of time talking to people about fines instead of just checking books in. She’d prefer that both patrons and staff have more positive interactions.

Initially, Melson’s library planned to eliminate fines temporarily when the pandemic began. The pandemic made the change permanent, because of the library’s planned student account partnership with five area schools. The schools were wary of signing on if there was a chance that parents would be surprised by late fines from the public library, Melson says.

For many respondents, dropping fines was a matter of empathy. Kambs points out that she turns things in late, too, and even her bank offers a grace period on bills. “If the bank is willing to do that for me, I feel like I can do that for my students.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a writer and editor with a passion for children’s books.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!