Beyond Black History Month: Duchess Harris Explains the Historical Influence of Black Americans

Dr. Duchess Harris, an academic, author, legal scholar, and a professor of American studies at Macalester College delivered the keynote speech at last year's Day of Dialog in Saint Paul, MN. Her enlightening speech discussed the far-reaching influence of African Americans and her path to becoming a global citizen.

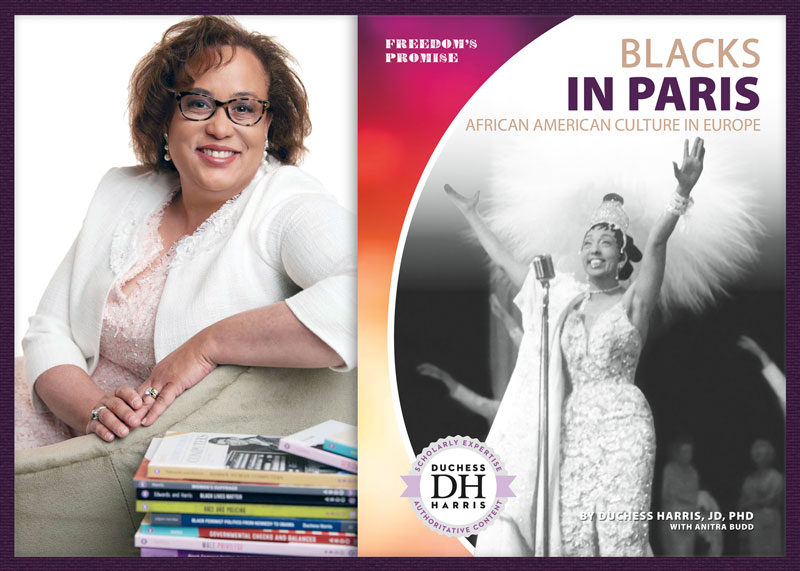

Author Photo by Tate Carlson

Why did I decide to curate a series of books entitled “Freedom’s Promise” for ABDO publishing? “Freedom’s Promise” is a new line of 36 books that I have curated for 4th–12th graders. These books cover African American topics. Some are familiar, such as the March on Washington. Others are not as readily known. For instance, young people aren’t exposed to the idea that Europe has influenced Black Americans and that Black Americans have influenced Europe.

The journey to create this book line was informed by my personal story. I only read two books in high school that prepared me to be a citizen of the world. They were Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Reading these two books were emotional learning experiences because they were coming-of-age stories that centralized Black girlhood. The Bluest Eye helped me think through what it was like to be a light-skinned African American girl in a world that thought that I should be darker but not too dark. Their Eyes Were Watching God helped me to answer if one could be in love, have human desire, and remain independent. I should mention that these books are fiction, but as actor Jesse Williams stated, “Just because we are magic, [it] doesn’t mean we aren’t real.” Young people need to learn the real-life experiences of African Americans in the world.

As eye-opening as these novels were, I arrived at college 32 years ago ill-prepared to imagine my own history as it related to global politics. I attended one of the most rigorous high schools in the nation that actually held classes on Saturdays. My elite New England boarding school curriculum required that we read the 14th-century poet Chaucer, yet I had no idea that African Americans had influenced culture in Europe.

Why do I share these stories with you? Partly because turning 50 made me nostalgic; but also, I have spent the last few years of my career writing books that reimagine European history. The one book that I will share with you is Blacks in Paris: African American Culture in Europe. The book starts with answering the question, “Why and when did Blacks go to Europe?”

Many African American soldiers wanted to fight in World War I. But U.S. military leaders didn’t think Black soldiers were as capable as white soldiers. President Woodrow Wilson believed that Black people should not hold positions of authority in the army. Most Black soldiers were forced to do noncombat tasks. They dug ditches and buried dead bodies. This was important but hard work. Discrimination from white troops made it even harder.

Approximately 40,000 Black soldiers in the U.S. Army did fight in World War I. They belonged to the Ninety-Second and the Ninety-Third divisions. These were two Black combat groups. The Ninety-Third’s 369th Infantry Regiment from New York became the most famous Black fighting unit. They were named the Harlem Hellfighters.

Within the 369th infantry, there was a jazz band. When the War was over and the musicians returned to the States, jazz performers were not received well. This influenced their decision to return to France.

Some of the best-known African Americans who settled in Paris were dancers and musicians. Many were drawn to the city’s nightclub scene. They launched their careers by performing in Paris’s famous nightclubs. Paris’s growing Black community also drew many African Americans to the city.

Many Black performers came to Paris during the 1920s and 1930s. This period was known as the Jazz Age. African American jazz performers wowed audiences with their music and styles.

One of the most famous members of the Paris jazz scene was Ada “Bricktop” Smith. Smith was born in West Virginia in 1894. She left home at the age of 16 to become a dancer and jazz singer. She toured across the country, and then she moved to New York City. A nightclub owner there nicknamed her “Bricktop” because of her red hair.

In 1924, Smith performed at a small Paris nightclub called Le Grand Duc. Eugene Bullard managed the club. He was a drummer and the first African American fighter pilot. He began working at the club after flying planes for France in World War I.

The performers were so successful, they inspired the Harlem Renaissance writers. Langston Hughes and many other African American writers spent time in Paris in the 1920s. Writers had heard stories about France from World War I veterans, jazz musicians, and others in the Black community.

Many Black writers stayed in Paris’s Montmartre district. This area became known as the Harlem of the City of Lights. Many well-known Black writers came to Paris after World War II. Among the most famous of these writers were Richard Wright and James Baldwin.

Richard Wright was born in 1908 on a plantation near Natchez, Mississippi. He moved to Paris in 1946. His grandparents had been enslaved during the American Civil War. His parents were born free after the Civil War. His family was poor. Wright used his writing to protest the mistreatment of Black people. He said that in Paris, he never experienced a moment of sorrow. This is important because he is a man who experienced quite a bit of sorrow.

Wright’s memoir, Black Boy, reflects on his life in the 1920s and 30s which included him witnessing a childhood friend being lynched and burned to death.

After this traumatic event, Wright migrated to Chicago and his experiences in the North inspired him to write the novel Native Son. This book was an immediate best seller; it sold 250,000 hardcover copies within three weeks of its publication. It was one of the earliest successful attempts to explain the racial divide in America.

The novel has endured a series of challenges in public high schools and libraries all over the United States. Many of these challenges focus on the content being deemed as "sexually graphic," "unnecessarily violent," and "profane." Despite complaints from parents, many schools have successfully fought to keep Wright's work in the classroom. Teachers who value Native Son believe that the themes actually “foster dialogue and discussion in the classroom” and "guide students into the reality of the complex adult and social world.”

It is not surprising to learn that Wright did not want his family to endure the hostile response to his work in the 1940s. Six years after the release of Native Son, Wright visited Paris, and the following year, he and his family relocated there.

Once in Paris, he was befriended by the novelist and writer and James Baldwin. Baldwin had moved from New York City to Paris in 1948. He left the States to escape discrimination and focus on his writing. By the time he arrived in France, he had already written many plays, stories, and essays. But Baldwin didn’t have much money. He didn’t know the French language.

Wright and Baldwin have lots of differences. The first is their generation gap. Wright was older and the youthful James Baldwin was critical of Native Son. Baldwin wrote an essay called “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” which accused Wright of constructing protest fiction as opposed to literature.

Depending on the extent to which you are a literary nerd, you might not realize what an insult this is. Wright returned the insult and gave a public lecture in the American Church in Paris. The title of the lecture was, “The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States.” He suggested that Black Writers such as Baldwin were too patriotic to critique the United States. Baldwin replied, “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Wright was not persuaded and became a French citizen. He never returned to the U.S.

Baldwin came back to the U.S. in 1963 for the March on Washington. That was the year that he published a collection of essays entitled The Fire Next Time.

Why do these two authors matter so much? If young people do not have a context for Wright and Baldwin, they really can’t understand Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me.

Between the World and Me, which won the National Book Award in 2015, is written in the same format as The Fire Next Time. In The Fire Next Time, Baldwin is writing to his nephew about the aftermath of the March on Washington. Coates chooses this format to write a letter to his son about the protests in Ferguson.

Why did Coates choose the title, Between the World and Me? He borrowed it from a Richard Wright poem of the same name. The opening stanza of the poem is about young Richard finding his friend who is burning to death in Mississippi. He writes:

And one morning while in the woods I stumbled

suddenly upon the thing,

Stumbled upon it in a grassy clearing guarded by scaly

oaks and elms

And the sooty details of the scene rose, thrusting

themselves between the world and me...

I wrote Blacks in Paris: African American Culture in Europe because we did not have this kind of work for young people in the 1980s. Writing these books in the “Freedom’s Promise” series has been cathartic. It’s allowed me to imagine myself reading them as a girl. More importantly, they are academically important because European history is now taught on college campuses to include the African American experience.

I hope that there will now be books in libraries that transform how we see the world and how we see ourselves in it. I was born with an active imagination. With the gift of an innovative publisher, I have been able to write stories that reflect imaginings between the world, and me.

Duchess Harris is the Curator of 115 books for 4–12th graders in the Duchess Harris Collection for ABDO Books. The topics include: "Being LGBTQ in America," "History of Crime and Punishment," "Slavery in America," "Race and Sports," "Perspectives on American Progress," "Class in America," "Protest Movements," "American Values and Freedoms," "Being Female in America," and "News Literacy." You can learn about her series, "Freedom's Promise," by listening to her Podcast (under that name), that she co-hosts with her eighth-grade son, Zachary Harris Thomas. When she is not writing children's books, she is a Professor of American Studies at Macalester College. Her courses include, "Black Public Intellectuals," "Race and the Law," and "The Obama Presidency."

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!