Creating Makerspaces for All: Lessons From the Experts

As part of SLJ’s Tech Trends series of webcasts in cooperation with ISTE, a panel of experts discussed makerspace learning and offered guidance on how to create and design an effective program.

Makerspaces, on the decline? Hardly, according to librarians, who remain at the forefront of the movement.

In fact, a recent School Library Journal survey revealed that 52 percent of librarians tap makerspace integration as the tech-related programming that they are most excited to learn about, surpassing coding. (See "School Librarians Excel in Coding Instruction, Maker Ed, SLJ Survey Finds")

SLJ convened a panel of four makerspace experts to examine how hands-on experiential learning develops critical thinking skills, fosters meaningful collaboration and builds community. The session, “Lessons from Model Makerspaces,”—part of SLJ’s Tech Trends series of webcasts in cooperation with ISTE —offered guidance on how to create makerspaces and design programs that engage participants.

Moderated by SLJ executive editor Kathy Ishizuka, the panel included Stephanie Chang, director of impact at Maker Ed; Heather Moorefield-Lang, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro; Tamara Pearson, associate director of school and community engagement at the Center for Education Integrating Science, Mathematics and Computing at Georgia Institute of Technology; and Josh Weisgrau, director of learning experience design for Digital Promise.

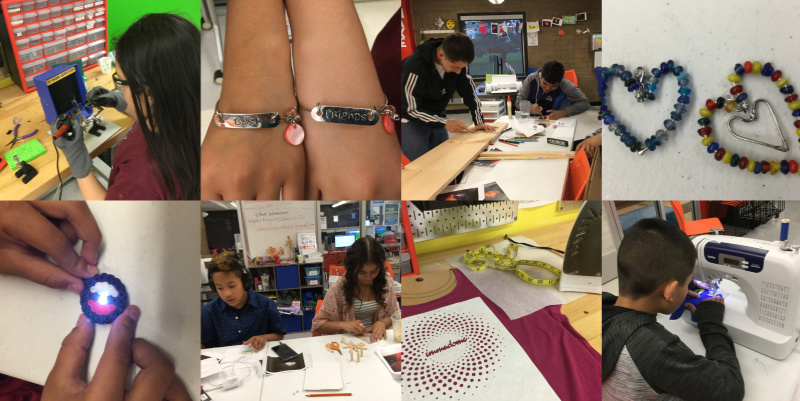

Makerspaces are a great fit for libraries because the two entities have many similarities, according to Weisgrau. For instance, they are sites of informal learning, act as interdisciplinary spaces, provide equitable access to materials and resources, are more than just resource closets, and serve the common goal of building community.

There’s also value in maker learning, he said. It gives participants agency, authenticity, and audience. Weisgrau cited an example where students identified two problem issues in their town and, in response, conceived and built a small library and food pantry called the Read and Feed.

“Maker learning is a practice that allows kids to build identities as makers and doers and that they see that everything in the world is designed and made by people and they see that they are empowered to make those things better,” he said.

Pearson champions a similar philosophy. Her outreach center at Georgia Tech works to expand STEM in schools and uses maker learning to tap into students’ passions. One such program, called Art in Motion, integrates computer science into art classes. High school art students were taken to a photography exhibit at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art. “We wanted students to create their own unique works of art that were inspired by what they saw,” she said.

Beyond the project itself, students presented their collection at the museum, explaining their work and answering questions from museum patrons. “Part of project-based learning is the importance of an authentic audience,” said Pearson.

More importantly, these concepts can be replicated anywhere, Pearson said. All that’s needed is an inspiration event. “It doesn’t need to be a large museum. It could be a theater production, public art, little gallery,” she said. “This is about students creating something that comes out of their imagination.”

Mix it up

Whether maker learning takes place in a dedicated physical space or activities are brought to another location, Chang said it’s important to consider “visible and invisible” components to the “space.”

“We notice what’s in front of our eyes and what might not be super obvious as well,” said Chang, whose nonprofit works with K–12 educators throughout the United States in formal and informal environments.

For instance, the Denver Public Library ideaLAB (pictured) has a mix of high tech, low tech, and no tech, and there are makerspaces at multiple branches around the community. Meanwhile, a library in Charlottesville, VA, rearranged the stacks to provide more space. Chang said they host a genius bar where students can volunteer and lend their expertise— technical or otherwise. It could be “just sharing their interests, projects, and passions.”

Effective makerspaces are also unique and diverse in who they serve, as well as adaptable to any group or project. “That’s incredibly important in thinking what access and equity means,” Chang said.

For Moorefield-Lang, accessibility is critical for makerspaces. “Accessible making can enrich the lives of people who are differently-abled,” she said.

Moorefield-Lang suggests creating a wide range of experiences for everyone regardless of ability, such as people who are visually or hearing impaired, those with mobility or cognitive impairments, or people who are on the spectrum or have cerebral palsy. That means evaluating your physical space and programming. Consider whether shelving can be reached or if pathways are wide enough.

“Is everyone welcome and will they feel welcome,” she said.

She referenced a makerspace at the University of Colorado Boulder, which has alternative texts and uses the 3-D printer to create tactile picture books to complement storybooks.

Another option is to create a fully online makerspace that is accessible to anyone, anywhere, and allows for collaboration across locations, said Moorefield-Lang. Such programs can offer online tools, such as digital storytelling tools, music and recording tools, video creation tools, presentation tools, and visual art creation tools.

As Weisgrau said, all it takes to be a champion for makerspaces is practice and preach. “Do it and lead it.”

Christina Joseph is an editor, writer, and content strategist.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!