Cartoonists Talk About "Charlie Hebdo"

In wake of the Charlie Hebdo shootings, players in the cartoon/graphic artist world gathered at the French Institute Alliance Française in New York City to discuss issues, including censorship, satire, and the power of the visual medium.

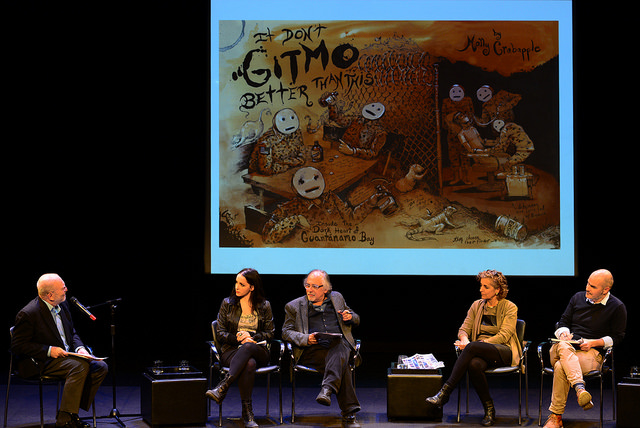

(From l. to r.) Emmanuel Letouzé, Molly Crabapple, Leonard Lopate, Françoise Mouly, and Art Spiegelman. All photo images courtesy of Michelle Sweatt / PEN American Center

According to cartoonist and journalist Molly Crabapple, “Art hits people in a visceral way. It gets under their skin.” She and other cartoonists and graphic artists were on hand February 19 at the “After Charlie: What’s Next for Art, Satire, and Censorship?” event at the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF), a panel that was moderated by WNYC radio host Leonard Lopate and organized by FIAF, PEN American Center, and the National Coalition Against Censorship to discuss the obstacles to free speech that cartoonists often face, the challenges of producing potentially offensive material, and whether Charlie Hebdo went too far. Françoise Mouly, art director of The New Yorker and Toon Books publisher, also attested to the power that cartoons wield—one that the written word lacks. Referring to The New Yorker cover that featured Sesame Street’s Bert and Ernie watching the Supreme Court on television (to represent the Court’s historic ruling on gay marriage), Mouly said, “Few people can really get a response, even when they are writing in The New Yorker.” Cartoons, however, are a different story. “This image got seen not only on the cover of the magazine," said Mouly, "but with the Internet, it got seen millions of times around the world.”

Françoise Mouly

While the dangers of censorship were stressed, Mouly and her husband, cartoonist and author Art Spiegelman, best known for his Pulitzer Prize–winning Maus (Pantheon, 1991), both raised the point that attempts to suppress incendiary material can often have an unintended effect: increasing publicity for a magazine or artist. Mouly discussed visiting Charlie Hebdo offices in 2006, when the magazine published its first Mohammed image, eliciting much controversy. After the outcry, Mouly said, the magazine’s editors were “thrilled,” as other journalists “rallied to their cause and denounced censorship,” bringing their circulation from 10,000 to 100,000 readers. Spiegelman agreed, citing the example of one of his drawings, published in Harper's magazine. The image accompanying his article, “Drawing Blood,” featured a woman’s naked torso, and as a result, Canadian bookstore Indigo refused to carry it. However, he said, the issue eventually became Harper’s best-selling issue of the 20th century. Panelists addressed another difficult topic: self-censorship, or the practice of self-editing one’s work to avoid potentially offensive content. Though Crabapple said that she’s committed to free speech, she also emphasized the potential damage that art can cause. “I won’t… [mess] with people who are already oppressed in my art," she said. "It’s not because I’m self censoring….I won’t use my art to punch down.” Spiegelman stated that often bans result in provocative art rather than stifling it. “Why on earth would I care about drawing Mohammed one way or the other until I’m told I can’t?” For him, restrictions often ignite a spirit of “youthful rebellion.” Similarly, Crabapple described her own run-ins with censorship—which, in one instance, she said, actually led to surprisingly creative results. When she visited Guantánamo Bay detention camp several years ago in order to document conditions for a piece for Vice, she was told that portraying the faces of the guards and soldiers was banned. The drawing Crabapple eventually produced accompanying her article, “It Don’t Gitmo Better than This,” depicted Guantánamo soldiers with dead-eyed smiley faces, with a prisoner the sole individual permitted an actual visage—an innovative and chilling choice.

Molly Crabapple discusses her cartoon for the piece "It Don't Gitmo Better than This." (from l. to r.) Leonard Lopate, Crabapple, Art Spiegelman, Françoise Mouly, and Emmanuel Letouzé.

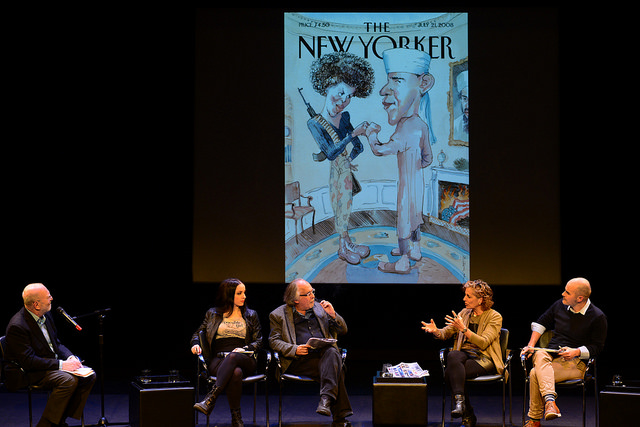

Though many have criticized Charlie Hebdo for its often crass-seeming images, with some alleging that the cartoons crossed the line into racism, Spiegelman pointed out that the publication was often quite sly. The cover that first brought Hebdo notoriety was published in 2006, showing a weeping Mohammed, head in his hands, saying, “C'est dur d'être aimé par des cons” (“It’s hard being loved by jerks”). Spiegelman pointed out that not only was the cartoonist taking aim at fundamentalists, rather than at all Muslims, the image also technically didn’t violate the ban on showing the prophet, as his face was covered. Mouly compared some of the Hebdo images to Barry Blitt’s The New Yorker cover that depicted President Barack Obama wearing Muslim garb and fist-bumping First Lady Michelle Obama in the Oval Office. Published right after Obama received the Democratic presidential nomination, the cover wasn’t intended to denigrate him but to demonstrate ignorance of the rumors and innuendo being said about him. However, there were still some who were afraid the image would be taken out of context, said Spiegelman. But, he said, “Nobody really was conned by this….[and] it actually functioned in an unusually great way. You could mention that [Obama] was black. It changed the discourse.”

Françoise Mouly compares the Hebdo cartoons to the controversial 2008 New Yorker cover. (from l. to r.) Leonard Lopate, Molly Crabapple, Art Spiegelman, Mouly, and Emmanuel Letouzé.

Cartoonist Emmanuel Letouzé tackled head on the criticisms that some have leveled against Hebdo for being disrespectful to Muslims. “Facts matter. You can do an analysis of how many cartoons they published in the past eight years that have anything to do with the prophet…. It’s probably less than one percent.” He stressed, too, that the Hebdo artists always drew with an underlying message or social commentary. Crabapple and Mouly warned, too, of the dangers of lumping all Muslims in with fundamentalists. Crabapple brought up the point that there is in fact an Islamic tradition of drawing the prophet and cautioned against assuming that all Muslims adhere to more extreme forms of the religion. She went on to describe seeing photos and videos of those around the Muslim world who showed solidarity with Charlie Hebdo following the attacks, from journalists in Syria to Muslims in Iran and Turkey. Mouly added, “Western media has accepted an edict from a very small minority [of Muslims],” and she cautioned against blindly swallowing that image of Islam without questioning or researching. Overall, the panelists stressed the importance of the thought-provoking message underlying cartoons. Said Letouzé, “Political cartoons need to [have] a point, something you can discuss. The cartoonists published in Charlie Hebdo made a point. It’s not an insult, it’s a political message.”RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!