2018 School Spending Survey Report

Bringing Black Lives Matter Movement to School

Educators navigated tough conversations and highlighted issues such as systemic racism during the national Black Lives Matter at School week of action.

Hall, one of the educators across the country who participated in the national Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action from February 5 to 9, was inspired to act and assisted in bringing the mission to the classroom by Teaching for Change, a DC-based non-profit organization based, with the goal of “building social justice, starting in the classroom.” Hall showed her older students a couple of videos that prompted thoughtful conversation, she says. “Some asked questions like ‘Why the slogan Black Lives Matter, not All Lives Matter?’ which was difficult to navigate,” says Hall, who describes her school population as a mix of Hispanic and African American students. She wanted the students to lead the discussion, not for her to “proselytize,” she says. In this case, she explained it wasn’t saying that all lives don’t matter, but that society doesn’t always recognize that black lives matter. She also explained that All Lives Matter is used to silence the voices in the Black Lives Matter movement. “There was a conversation that I think, at least, started to change their minds and open their minds about the kinds of things that some of the students experience and most of the students witness whether they know it or not,” Hall says.

Hall, one of the educators across the country who participated in the national Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action from February 5 to 9, was inspired to act and assisted in bringing the mission to the classroom by Teaching for Change, a DC-based non-profit organization based, with the goal of “building social justice, starting in the classroom.” Hall showed her older students a couple of videos that prompted thoughtful conversation, she says. “Some asked questions like ‘Why the slogan Black Lives Matter, not All Lives Matter?’ which was difficult to navigate,” says Hall, who describes her school population as a mix of Hispanic and African American students. She wanted the students to lead the discussion, not for her to “proselytize,” she says. In this case, she explained it wasn’t saying that all lives don’t matter, but that society doesn’t always recognize that black lives matter. She also explained that All Lives Matter is used to silence the voices in the Black Lives Matter movement. “There was a conversation that I think, at least, started to change their minds and open their minds about the kinds of things that some of the students experience and most of the students witness whether they know it or not,” Hall says. THE BEGINNING

Taking the Black Lives Matter movement into schools is believed to have started in 2016 at John Muir Elementary School in Seattle. The school was making an effort to support its black student population. As part of that, teacher DeShawn Jackson organized an “Black Men Uniting to Change the Narrative,” a celebratory event with the goal of countering the negative image of black men that kids often see in the media. He invited more than 100 black men to greet the children at school one day, visit classrooms and play with them at recess. In a sign of solidarity, teachers planned to wear t-shirts that read, "We Stand Together" or "Black Lives Matter." When that last detail was made public, the school received angry phone calls and at least one threat that forced the district to cancel the planned event and send bomb-sniffing dogs through the school. But when no danger was found and the school was opened, people still came. The men high-fived the children as they went into the school, while staff and parents stood by in Black Lives Matter T-shirts. From there, Seattle educators wanted to have a citywide inclusion of Black Lives Matter at schools. In 2017, it became more official and hit both coasts as Seattle and Philadelphia educators organized Black Lives Matter at School lessons and activities. That same year, in Rochester, N.Y., there was a day to "understand and affirm black lives" after a controversy that occurred when Rochester high school football players kneeled during the national anthem.GOING NATIONAL

This year, the movement went national with an organized a week of action. Teachers' unions, including those in New Jersey, Milwaukee and Chicago, issued statements in support of their members joining the week of action and some school districts passed resolutions or publicly supported the cause, but any activity, event or addition to curriculum was voluntary on the part of the educator or school. The week of action had three “national demands”: end zero tolerance (restorative justice in all schools), mandate black history and ethnic studies, and hire more black teachers. Its 13 “principles” were: diversity, restorative justice, unapologetically black, black families, black women, black villages, globalism, loving engagement, empathy, queer affirming, transgender affirming, intergenerational, and collective value. The national Black Lives Matter at School organization and local groups of educators offered curriculum resources, lesson plans, book and video recommendations, and professional learning sessions. A Twitter search of #BlackLivesMatteratSchool showed some of what was happening in classrooms around the country, as well as more public displays of support to the cause. Teachers wore Black Lives Matter T-shirts. School signs declared “Black Lives Matter.” Some schools flew a Black Lives Matter flag. In one DC-area school, eight graders created a lesson they taught to first graders about not judging people by what they look like. In New Jersey, there were lessons and events in a few towns and districts, such as Maplewood-South Orange, Newark, and Montclair. But despite union support and a lot of initial interest from educators around the state, there was not obvious widespread participation. T.J. Whitaker, a teacher at Columbia High School in the Maplewood-South Orange (NJ) district, was actively involved in talking to state educators about Black Lives Matter at School. He believes those who shied away from implementing the lesson plans or protested the idea were “reacting to Black Lives Matter” instead of looking closely at the principles and demands, according to Whitaker, who is also the founder of MAPSO Freedom School, a group that helped organize many of the Black Lives Matter events in its district. “Nothing is, in my opinion, overly radical, so I wished folks took a look at the resource list,” he says. “It’s Common Core related, it connects to what we’re supposed to be doing. ‘Black Lives Matter’ possibly scared some folks.”

The week of action had three “national demands”: end zero tolerance (restorative justice in all schools), mandate black history and ethnic studies, and hire more black teachers. Its 13 “principles” were: diversity, restorative justice, unapologetically black, black families, black women, black villages, globalism, loving engagement, empathy, queer affirming, transgender affirming, intergenerational, and collective value. The national Black Lives Matter at School organization and local groups of educators offered curriculum resources, lesson plans, book and video recommendations, and professional learning sessions. A Twitter search of #BlackLivesMatteratSchool showed some of what was happening in classrooms around the country, as well as more public displays of support to the cause. Teachers wore Black Lives Matter T-shirts. School signs declared “Black Lives Matter.” Some schools flew a Black Lives Matter flag. In one DC-area school, eight graders created a lesson they taught to first graders about not judging people by what they look like. In New Jersey, there were lessons and events in a few towns and districts, such as Maplewood-South Orange, Newark, and Montclair. But despite union support and a lot of initial interest from educators around the state, there was not obvious widespread participation. T.J. Whitaker, a teacher at Columbia High School in the Maplewood-South Orange (NJ) district, was actively involved in talking to state educators about Black Lives Matter at School. He believes those who shied away from implementing the lesson plans or protested the idea were “reacting to Black Lives Matter” instead of looking closely at the principles and demands, according to Whitaker, who is also the founder of MAPSO Freedom School, a group that helped organize many of the Black Lives Matter events in its district. “Nothing is, in my opinion, overly radical, so I wished folks took a look at the resource list,” he says. “It’s Common Core related, it connects to what we’re supposed to be doing. ‘Black Lives Matter’ possibly scared some folks.” CLASSROOM IMPLEMENTATION

In Hall’s library, the kids’ concern was for one another. “They wanted to make sure that all of the students were part of the space and could be represented,” she said. “One of the videos I showed was a model school where only five percent are African American, but all the students recognize that black lives matter. That was my jumping off point. It doesn’t only have to be black people saying, ‘Black Lives Matter,’ We can all acknowledge that this is a group that needs our support, that needs to be recognized.” Still, many of the students kept coming back to inclusion, and not as a way to simply include themselves. “It wasn’t just the Hispanic kids, some of the black kids were saying, 'All lives do matter,'” says Hall, adding that one black student insisted on putting that on her poster Hall had them make.

Photo by Lindsay Hall

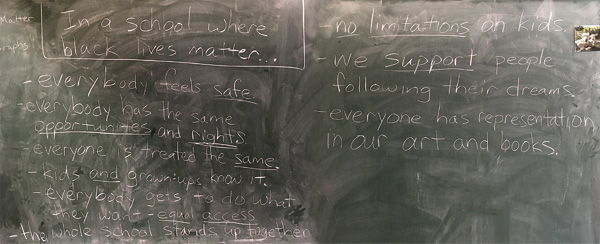

Around Hall’s school, students made protest signs in art class and discussed Black Lives Matter issues in their morning meetings. Those conversations continued into her library, where Hall went to her most powerful tool for her younger kids. “Here in the library, I’m lucky to have these books,” she says. “Something I’m very passionate about is showing kids books that display their experience, books that have kids that look like them.” She chose one of her favorites, Precious and the Boo Hag by Patricia McKissack, about an African American girl home alone with a stomachache. “They don’t notice in the sense that ‘Oh, this book is empowering me,’” Hall says. “But they see a story that reflects them and their lives.” She also wanted to show different perspectives on the black experience, so she read Stephen Davies' Don’t Spill the Milk, about a girl in Africa. In Baltimore, Nina Sethi and Gabby Arca–like Hall–worked closely with Teaching for Change to find the most appropriate way to bring the Black Lives Matter message to the third grade class they co-teach at the predominantly white and affluent private Sheridan School. Not wanting their students to fixate on the violence, they chose to highlight systemic racism and its impact. They read Milo’s Museum, about a black girl who creates her own museum after going on a school field trip and not seeing herself or her community represented in the museum they visited. They also read a news story about black preschoolers being suspended more than white ones. The kids connected the preschoolers in the story to their kindergarten “buddies,” wondering how anyone could punish young kids like their little friends. They said things such as, “This is so unfair,” “This is wrong,” “This makes me angry.” One black student told them she didn’t like to talk about it, “because it makes me sad.” Similar conversations were going on across the country. At a private school in Menlo Park, CA, Toni Ouradnik was talking to her class of seven- to nine-year-olds about the targeting and marginalization of people of color. “We used examples that were developmentally appropriate, like getting stopped more often by the police,” the Peninsula School teacher wrote in an email. “I also introduced the idea of some people having different expectations of achievement for different groups of people. We then talked about how a school could show that people of color matter by finishing the sentence "In a school where Black Lives Matter..." The students brainstormed in small groups before coming together as a class and creating a list that included, “Everybody feels safe;” “Everyone has the same opportunities and rights;” and “everyone has representation in our arts and books.”

They also read a news story about black preschoolers being suspended more than white ones. The kids connected the preschoolers in the story to their kindergarten “buddies,” wondering how anyone could punish young kids like their little friends. They said things such as, “This is so unfair,” “This is wrong,” “This makes me angry.” One black student told them she didn’t like to talk about it, “because it makes me sad.” Similar conversations were going on across the country. At a private school in Menlo Park, CA, Toni Ouradnik was talking to her class of seven- to nine-year-olds about the targeting and marginalization of people of color. “We used examples that were developmentally appropriate, like getting stopped more often by the police,” the Peninsula School teacher wrote in an email. “I also introduced the idea of some people having different expectations of achievement for different groups of people. We then talked about how a school could show that people of color matter by finishing the sentence "In a school where Black Lives Matter..." The students brainstormed in small groups before coming together as a class and creating a list that included, “Everybody feels safe;” “Everyone has the same opportunities and rights;” and “everyone has representation in our arts and books.”

Children's ideas on what a school where black lives matter should be. Photo by Toni Ouradnik.

Hallie Herz teaches sixth and seventh grade social studies at the Park School in Baltimore, MD. A progressive, private school, the week's curriculum and lesson plans "fit right into the things I was already doing," says Herz. She chose to have her sixth grade students participate in a role play project, with the kids taking on the lives of black Muslims. They looked at stereotypes and the long history of black Muslims in the United States. "The kids really got into it," she said. They asked a lot of questions, she said, such as 'Where does Islamophobia come from if it's such a peaceful religion?' In her seventh grade class, they discussed the Black Lives Matter at School 13 principles and Herz asked them what they have observed in their lives. As with some previous lessons, Herz braced herself for calls from parents, but they didn't come. It's a school and community that values equity and advocacy, she says. "There’s more buy-in here than there might be at other schools, but that doesn't mean I don’t have students who aren’t really doubtful [asking] ‘Why do we talk about race so much? Why do we talk about women so much?'" she says.NOT WITHOUT CONTROVERSY

In addition to school day lessons and activities, many groups ran events after school and in the evening. In New York City, that included conversations about Black Lives Matter in education and standardized testing and race, as well as a teach-in at the Museum of the City of New York on activism. In one after school workshop, a student at Sunset Park High School in Brooklyn, NY, created her own painting based on one by artist Madame Muse. The painting, which showed a young black girl spray painting “Bigger than Hate” on a wall (changing graffiti that was already there, and turning an “N” into a “B” and a single word into a larger message) while a police officer points a gun at her. The painting was hanging in the lobby of the school when someone took a picture, posted it on Facebook and urged people to call and complain. In the ensuing controversy, the girl’s painting was moved to another part of the school. The story was reported on in the New York Post and some tweeted about the incident.

In one after school workshop, a student at Sunset Park High School in Brooklyn, NY, created her own painting based on one by artist Madame Muse. The painting, which showed a young black girl spray painting “Bigger than Hate” on a wall (changing graffiti that was already there, and turning an “N” into a “B” and a single word into a larger message) while a police officer points a gun at her. The painting was hanging in the lobby of the school when someone took a picture, posted it on Facebook and urged people to call and complain. In the ensuing controversy, the girl’s painting was moved to another part of the school. The story was reported on in the New York Post and some tweeted about the incident. Looking ahead

The heated controversy showed there is a long way to go before Black Lives Matter at School will be accepted by all without debate. In Seattle, not two years since the Muir Elementary phone calls and threat, the city school board tried to preempt arguments from anyone opposed. In its resolution endorsing citywide participation in Black Lives Matter at School, the board included a note to any who might object: “WHEREAS shouting loudly that ‘Black Lives Matter’ does not negate our commitment to ALL of our students, but rather elevating Black students struggle to trust that our society values them, we must affirm that their lives, specifically, matter,” it read. Despite the need to make these kinds of statements, the educators involved believe not only in the importance of the week but also its positive impact on the students. The hope is that this year brought the country one step closer to all schools taking part in Black Lives Matter at School, with a goal of education and change. “On a personal level, I hope in my school gets [more] involved, hope it spurs us to be engaged, to be more reflective,” says Herz. “On a larger level, I hope that the demands are met. I really hope we see some more districts and schools jump aboard, see more pressure to make these changes. It’s a week of action and the goal is action.”RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Jamila Felton

Thank you for writing this article. I was excited to observe student work from the Black Lives Matter Week of Action at The Inspired Teaching School in DC. Students of all ages and all backgrounds benefit from the lessons. All social justice issues are critical for students, teachers, and families to explore and understand.Posted : Feb 27, 2018 12:27

Dr Kiran Frey

Excellent effort being made by so many educators to change attitudes. Children are our biggest hope for change!Posted : Feb 26, 2018 03:39