Educators Weigh In on Summer Reading Lists in SLJ/NCTE Survey

Suggestions include culling To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Gatsby, and works by Shakespeare, as well as adding New Kid and Firekeeper's Daughter, among other titles.

|

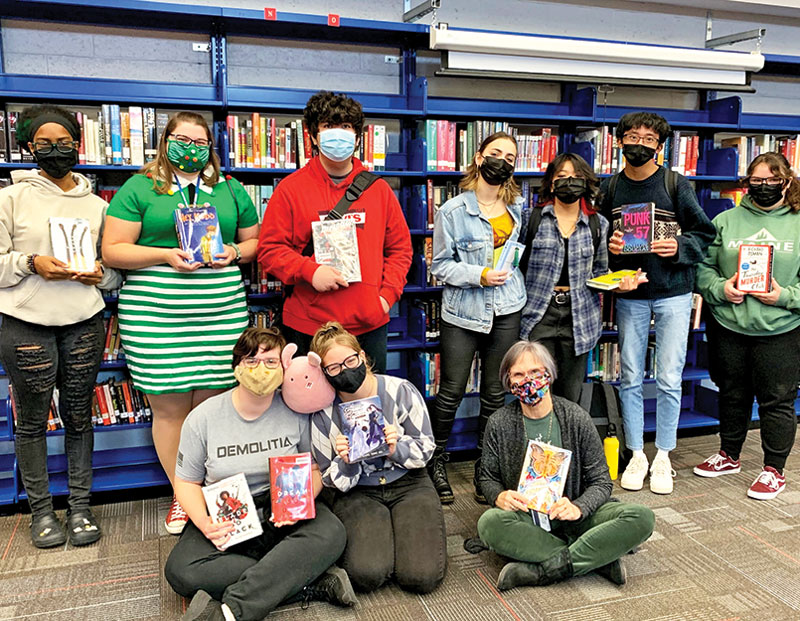

Lizanne Johnson’s Readers Café lunchtime book club at Groton (CT) High School. |

The final bell of the school year is the sound of freedom for students, and summer reading assignments can be pushed to the bottom of the backpack and to-do list. Whether summer reading is suggested for fun or required for the next school year, students often see it as dreaded, uninteresting homework. Worst case, it can backfire for kids who already have a hard time reading, like the students in Larissa Hinton’s reading support class at Norview Middle School in Norfolk, VA.

“A lot of my students do not care for reading, and they’ll say all these books are boring,” says Hinton, who has taught sixth to twelfth grade English and currently works with kids at the Title I school to boost their literacy proficiency and reading enjoyment. “It drives me crazy to see these summer reading lists that keep having books that don’t work or appeal at all to students.”

Hinton was one of nearly 100 librarians, classroom teachers, and educators who participated in the SLJ and NCTE’s Summer Survey. The selections and purpose of suggested or required lists have left many teachers and librarians divided, and survey results reflect the split. While teachers’ assignments are often driven by curricular mandates, librarians frequently want kids to read what they enjoy, with the goal of keeping them engaged and turning them into independent readers.

Literacy experts see these programs as a tool to fight the “summer slide,” or the loss of reading achievements gained during the school year. Many respondents agree that the initiatives are a vital way to keep students reading, but others want to get rid of them. Some are dedicated to “the classics”—tried-and-true, yet often dated, books. On the other side, many say that newer titles covering culturally relevant topics resonate better with kids and teens.

To Kill a Mockingbird and The Great Gatsby were the top books people wanted cut from lists, while favorite titles to add included the graphic novel New Kid by Jerry Craft and the novel The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. Instead of historical fiction, some respondents suggested science fiction and manga. Many wanted books about more diverse characters, by diverse authors, and others proposed giving students more agency and reading choice. Additionally, respondents noted an availability problem: Old titles can be in low supply in library systems, or be out of print.

Overall, the books respondents suggested removing include To Kill a Mockingbird, Shakespeare's works, The Great Gatsby, Hatchet, The Catcher in the Rye, The Outsiders, Lord of the Flies, The Grapes of Wrath, Huckleberry Finn, The Little House on the Prairie, Tom Sawyer, Jane Eyre, Great Expectations, Little Women, Pride and Prejudice, Island of the Blue Dolphins, Of Mice and Men, Anthem, and 1984. They suggested adding New Kid, The Hate U Give, Firekeeper’s Daughter, Long Way Down, Stamped, The Poet X, All American Boys, Born a Crime, Front Desk, I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, The Crossover, and Refugee.

“Students cannot relate to some [older books] anymore. I understand that classics should be appreciated, but I think it’s time to allow books published from the 2000s to be given a fair shake,” Hinton wrote. “I honestly think we need to revamp the whole idea of summer lists.”

|

Survey Methodology: The SLJ and NCTE Summer Reading Survey asked K–12 librarians and teachers to identify titles they would suggest removing

|

The power of choice

Summer reading programs range from leisurely book clubs to mandatory assignments; objectives range from familiarizing students with authors or genres in next year’s class to keeping kids learning year-round. In school programs, these initiatives are tied to the grade level and subject of the class. An eighth grade English class might have optional choices of a variety of subjects and genres, while an honors British literature or AP composition course might have a list of classics with a mandatory writing assignment.

“Teachers really are playing by a different set of rules—the AP rules,” says Teka McCabe, library media specialist at Briarcliff Middle School and High School in Briarcliff Manor, NY. While there is no set list mandated by the College Board Advanced Placement program, there are books commonly covered on the AP tests, which pressures teachers to teach them, McCabe explains.

Even under strict learning requirements, a little choice can go a long way, McCabe says. Teachers can design lists and assignments for AP and honors classes that give students some freedom to pursue their interests.

Still, “something of value must be done with the summer reading in the classroom at the start of school, otherwise students regard it as pointless and parents complain about the demand on their child’s time,” wrote survey respondent Kimberly Davis, head of the English department at Heritage Christian School, a pre-K–12 private school in Indianapolis, IN. “We have had the most success when we permit choice.”

Davis has refined her approach. In the past, some English teachers at her school assigned one book; sophomores in World Literature and Composition would read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and complete a fall unit on it. “Most kids hated it,” Davis says. “They needed more guidance to read it well and read it with understanding. That was defeating our purposes.”

This year, in her British literature class, Davis offered a selection of titles such as The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Remains of the Day, and Ivanhoe. She also allowed students to choose almost any novel by specific authors, including Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, or from J. R. R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, which greatly expanded options, she says. At the start of school, Davis coached them to find contrasts and abstractions in their selected book for an essay—like explaining how an author uses contrast to illuminate themes of forgiveness. These assignments provide concepts and skills that the class circles back to through the year, Davis says.

Davis prefers books of “verified quality” that help students “recognize what’s common across humanity, time, and cultures.” While she and her fellow teachers acknowledge the historical context, Davis maintains that there’s value in learning about past cultures and societies from classic texts.

“Most contemporary things haven’t had the chance to be tested by time, and so I would want to screen them,” she says.

Contemporary reads that connect

Teachers and librarians may also want to keep older titles because they already have lessons planned around them, Hinton says. With new books, they must start from scratch.

Still, Hinton has successfully taught contemporary reads that overlap—or better address—themes taught in classics. Her students read All Rights Reserved by Gregory Scott Katsoulis, where copyright laws in a dystopian America put a price on every word. The class discussed technology’s impacts on society, free speech, rebellion, and other concepts taught from George Orwell’s books.

“[Classic] books can be over 200 years old. What else could our teens be learning that they can’t learn from more current books?” says Faith Healy, teen public librarian at the Crest Hill Branch of the White Oak (IL) Library District, who also seeks contemporary titles that could replace classics. Instead of 1984, she suggests Sanctuary by Paola Mendoza and Abby Sher, which follows a young girl and her undocumented immigrant family in a not-so-distant future America where citizens are tracked with a chip. The plot is Orwellian and ‘big brother,’ ” she says, “but also talks about immigration instead in the future, so it’s more fun.”

And summer reading should be fun, she adds. Growing up, Healy loved reading—but loathed required books like The Great Gatsby. The language was difficult, the characters unrelatable, and “trying to write a five-page essay on that was a nightmare.” Healy now collaborates with librarians at local schools to recommend diverse book titles.

Pushing for change can be fraught for educators. Hinton supplied data to administrators to show the value of reading and discussing books that cover suicide and police violence against African American communities. While McCabe builds lists that better reflect her students at Briarcliff Middle School and Briarcliff High School, she got pushback from parents who prefer classics. But she stands firm that creating more representative lists with newer titles helps make reading more appealing, and students feel more included when they return to school.

“My goal is to make them readers first, and then lovers of literature can come next. If they’re not reading for pleasure, they’re not going to be reading classics,” says McCabe.

Diversifying lists for AP and honors courses could also help in enrolling kids from racial and socioeconomic backgrounds that traditionally don’t sign up, says school library media specialist Lizanne Johnson. The English department at Robert E. Fitch Senior High School in Groton, CT, where she works, is pushing for a more inclusive list. But many decisions are outside the control of individual teachers, librarians, and school districts. “It has to come from AP to change their list” and books on tests, she says. “We should be including more interesting books to get our diverse population of kids taking AP English, which would be huge money savings for them in college.”

Johnson and Hinton suggest creating summer lists with students: Kids can vote on what they want added and removed, and educators can review. Each fall at Groton Middle School and Fitch High School, Johnson interviews students who need reading support to get feedback and set up reading goals. The first question she asks is about their summer reading habits.

“Most of them will admit they don’t read over the summer, and then those who do complete their summer reading assignments say they do it the last two weeks of vacation,” she says. “The importance for me is that they choose the book. It’s got to be what they want to read, because if they’re not enjoying it, it just defeats the purpose of summer reading.”

Based on student input, Johnson runs a summer book club at the middle and high school. Students pick the title and discuss it. Johnson and colleagues facilitate and try to make any assignments easy—adding a Google slide with a sentence about the book or a picture of them reading for the middle schoolers, for instance. She’d rather have students’ time be spent reading, not doing the assignment.

“Summer reading should be for pleasure,” Johnson says. “I had a student apologize for taking a graphic novel. Never apologize for what you’re reading. Enjoy it.”

Reading lists look different from school to school—and they should, to reflect and serve their communities, McCabe notes. “Keeping things popular and appealing to the kids in front of me—that’s what I think is most important.”

Look for for recommended booklists from SLJ and NCTE booklists coming son on slj.com and included in the June print issue.

Lauren J. Young is a science journalist in New York City.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing