As COVID Continues to Pressure Kids and Communities, Libraries Lean In to Support Mental Health

Serving on the front lines, engaging with the public, libraries can be a critical asset to mental health.

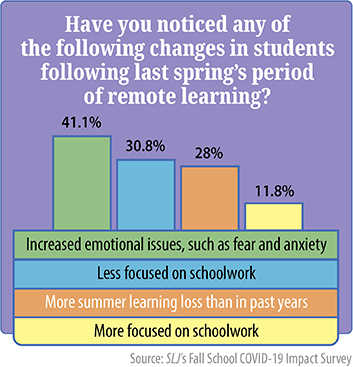

Forty-one percent of K–12 librarians responding to a September School Library Journal survey have witnessed more “emotional issues” among students, including fear and anxiety. That observation rises to 52 percent in middle schools. Students overall, 31 percent of librarians reported, appear less focused on schoolwork. (For more on SLJ’s survey, see “Ahead of the Curve: School Librarians Innovate and Take on New Responsibilities”)

Mental health is a serious matter, and acute conditions require professional diagnosis and care. But even a lay observer might safely assume that the sheer uncertainty of living in these times is affecting us all.

“The trauma and stress is what you don’t know,” says Valerie Bell. The executive director of the Athens (GA) Regional Library (ARL) (pictured), Bell has therefore made consistent, frequent communication with staff and the public a priority during the pandemic. Situated in Clark County, a longtime COVID hot spot, the library only recently reopened its doors for limited in-person service on October 5.

ARL serves a unique community that encompasses the University of Georgia (UGA) and a sizeable low-income population—Athens’s poverty rate is 34 percent.

“Our community is wrestling with all the things the nation is wrestling with. Food insecurity i s a major issue,” says Bell, who also cites the killing of George Floyd and the renewed call for social justice. “The community is feeling stressed.”

s a major issue,” says Bell, who also cites the killing of George Floyd and the renewed call for social justice. “The community is feeling stressed.”

Across the country, Jane Gov, youth services librarian at Pasadena Public Library, says, “What we’ve been seeing in the last few months is… [teens] don’t call it ‘mental health issues,’ but lack of motivation, feeling sad. I think lack of motivation is the biggest one.”

SLJ survey takers also point to a general aura of disengagement. “Students are disconnected; we’re still figuring out how to build community in the virtual school setting,” said one.

Several librarians, in school and face to face, cited the barrier presented by masks, which make facial expressions difficult to read.

When asked to identify possible changes in students, one librarian simply wrote, “I do not know. The whole situation is weird.”

For Gov, having personal relationships with kids has been key. Her investment in leading a longtime teen intern program at Pasadena has paid off, most recently enabling the librarian to recognize a serious issue with one intern and broach it directly with the teen and her parents.

Both Gov and Bell have the benefit of their libraries’ participation in mental health programs involving community partners and formal mental health training for library staff.

Athens “was just hitting our stride,” says Bell, with the Trauma-Informed Library Transformation (TILT) project, when COVID hit. Through funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS), TILT brought training and interns to the library via UGA’s school of social work.

Pasadena was among the participants in the California State Library Mental Health Initiative, funded by IMLS. While COVID disrupted Initiative-sponsored programs over the summer, Gov notes the impact. “Quite honestly, [the program] forced the library to hold mental health training for staff,” she says. The result? An informed team has emerged, who support one another in this work.

Meanwhile, in Athens, Bell’s proposal for a new hire has been approved. The library, with UGA’s help, will get a part-time social worker this year.

The pandemic will resolve at some point, not so readily its effects, particularly among the most vulnerable. For ongoing service on the front lines, libraries will need public support.

Kathy Ishizuka

Editor-In-Chief

@kishizuka

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!