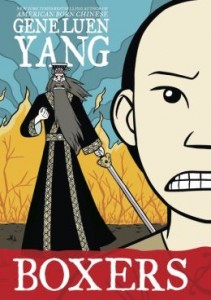

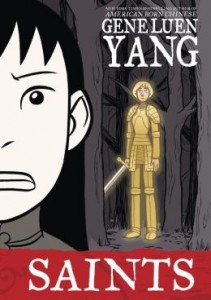

A Twice-Told Tale of Rebellion in China | Gene Luen Yang’s ‘Boxers & Saints’

In 'Boxers' and 'Saints,' two new graphic novels from the Gene Luen Yang, the author examines the Boxer Rebellion from both sides of the conflict. In this interview, the author comments, "the more I learned, the more ambivalent I felt....I could sympathize with both sides."

Did you know from the inception of this project that you would tell the story of the Boxer Rebellion in two volumes? Yes. I wanted to tell a story about a murderer and his victims. I wanted to tell compelling and sympathetic stories about both [sides]. Under different historical circumstances, these characters could have led very different lives. Under different circumstances, they might have become family. Several of the people in the books are historic figures, aren't they? In The Origins of the Boxer Uprising [Berkeley, 1987], Joseph Esherick talks about itinerant martial arts masters that would roam around the countryside training young people in the martial arts [many of whom joined the Brother-Disciples of the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist]. One was Red Lantern [who teaches Little Bao martial arts]. Another was Master Lee [whom Red Lantern directs Little Bao to visit]. There was a rumor that Master Lee had a mystical eye in the middle of his stomach. He only showed up in a sentence or two in Esherick's book, but I made him into a kind of archetype. On the Saints side, there was a book put out by the Taiwanese Catholic Church with details about the canonized saints. Dr. Won, the acupuncturist [who helps convert Four-Girl to Catholicism], is one of the canonized, and his baptismal name is Mark Ji. He's Saint Mark now. He was known for treating the poor for free, and as a leader of the church. In his middle age, he developed a stomach disease, and the only thing that relieved his pain was opium. When his stomach disease stopped, he couldn't kick [the habit]. He was killed during the Boxer Rebellion. Many see him as the patron saint of addicts. In the artwork, you create a visual motif for the spiritual experiences of each protagonist. In Boxers, it's the transformation of the Brother-Disciples of the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist into the deities that Little Bao knows from the operas he attended. When I read about the Boxers, I discovered that their roots were very spiritual. No one knows for sure how [the Boxer Rebellion] started because it began in the poor villages, and that history is hard to track. In the late 1800s, some sort of movement developed, a combination of spirituality with the martial arts. There was an idea that the deities would visit these young men and make them amazing warriors. I think it was sort of an expression of desperation. There's been some writing that compares this with Ghost Dancing in Native American history. When a culture feels existentially threatened, these sorts of superpowers come out.

Did you know from the inception of this project that you would tell the story of the Boxer Rebellion in two volumes? Yes. I wanted to tell a story about a murderer and his victims. I wanted to tell compelling and sympathetic stories about both [sides]. Under different historical circumstances, these characters could have led very different lives. Under different circumstances, they might have become family. Several of the people in the books are historic figures, aren't they? In The Origins of the Boxer Uprising [Berkeley, 1987], Joseph Esherick talks about itinerant martial arts masters that would roam around the countryside training young people in the martial arts [many of whom joined the Brother-Disciples of the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist]. One was Red Lantern [who teaches Little Bao martial arts]. Another was Master Lee [whom Red Lantern directs Little Bao to visit]. There was a rumor that Master Lee had a mystical eye in the middle of his stomach. He only showed up in a sentence or two in Esherick's book, but I made him into a kind of archetype. On the Saints side, there was a book put out by the Taiwanese Catholic Church with details about the canonized saints. Dr. Won, the acupuncturist [who helps convert Four-Girl to Catholicism], is one of the canonized, and his baptismal name is Mark Ji. He's Saint Mark now. He was known for treating the poor for free, and as a leader of the church. In his middle age, he developed a stomach disease, and the only thing that relieved his pain was opium. When his stomach disease stopped, he couldn't kick [the habit]. He was killed during the Boxer Rebellion. Many see him as the patron saint of addicts. In the artwork, you create a visual motif for the spiritual experiences of each protagonist. In Boxers, it's the transformation of the Brother-Disciples of the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist into the deities that Little Bao knows from the operas he attended. When I read about the Boxers, I discovered that their roots were very spiritual. No one knows for sure how [the Boxer Rebellion] started because it began in the poor villages, and that history is hard to track. In the late 1800s, some sort of movement developed, a combination of spirituality with the martial arts. There was an idea that the deities would visit these young men and make them amazing warriors. I think it was sort of an expression of desperation. There's been some writing that compares this with Ghost Dancing in Native American history. When a culture feels existentially threatened, these sorts of superpowers come out.  In Saints, the visual motif occurs when Joan of Arc visits Four-Girl. Was that an early development in the shaping of the two books? On the Chinese Catholic side, I drew from my experiences within that community. For instance, I have a relative who converted to Catholicism as an adult. Her childhood was the inspiration for Four-Girl. She was born on a bad day, and because of that, her grandfather hated her. She couldn't find a place for herself in Chinese stories, so she had to look elsewhere. I debated about which saint to use. I settled on Joan of Arc because of how similar her story is to the Boxers. She's living in a country under siege by a foreign power, and she's invested with a spiritual power that inspires her to fight that foreign power. Lark Pien did the color for both books. Did you talk about the palette together? That seems so essential to the continuity of the historical events shared by the two books, and also in the way the spiritual transformations of the two protagonists are conveyed. We had a lot of conversations about that. Lark is a really accomplished cartoonist in her own right, with books such as Long Tail Kitty [Blue Apple, 2009]. I knew that the scope of each book would be different—even the physical geography would be different. The Boxers went on a long journey to the capital, and the villagers for the most part stayed put. I knew the books wouldn't match up in terms of scope, and I wanted Lark, with her colors, to indicate that. I gave her lots of pictures of Chinese Opera. We wanted those battle scenes to be bright and colorful, and for Boxers to read like an epic. We wanted Saints to be more personal, like autobiographical comics--they're often monochromatic, one or two colors, most done in French gray. We talked about how Joan of Arc had to seem like she was coming in from another world, as if she'd just stepped out of a European illuminated manuscript. Sometimes the cultural clashes were simple misunderstandings, weren't they? The incident where Little Bao meets German soldiers [on the road] was based on an actual confrontation between Chinese villagers and German soldiers. It was a fight about the right of way. The Chinese understanding was the person with the larger load had the right of way; the Germans believed that the higher rank had the right of way. It ended up becoming a bloody incident. One of the most heartrending scenes in the books involves the Hanlin Academic Library. Tell us more about that. The burning of that library was tragic. A lot of stuff was lost in that fire that we'll never have again. The Europeans left it unguarded, and the Boxers burned it down. And it was the European scholars who tried to save that library. Chinese history is very complex. If you look at China in the last 100-200 years, it's vacillated between clinging too tightly to the past, and trying to get away from history completely. Around the turn of the [20th] century, there was this holding on to the past that weakened China and maybe made them fear Western technology. During the Cultural Revolution they were trying to excise the history, and it caused tremendous pain. That's a driving part of that section of the book. You can't get away from your history; you can't burn down your own libraries. What's next for you? I have a book coming out next year that I did with Sonny Liew, an artist from Singapore. I wrote it after Boxers and before I finished Saints. I wanted to write a more uplifting story. I found a link to a blog, where they highlight Golden Age characters, and I discovered a superhero named Green Turtle, created by one of the first Chinese artists in the 1940s, Chu Hing. The rumor is that he wanted Green Turtle to be Chinese American. The main character's face is almost always obscured. Sonny and I are telling his origin story.

In Saints, the visual motif occurs when Joan of Arc visits Four-Girl. Was that an early development in the shaping of the two books? On the Chinese Catholic side, I drew from my experiences within that community. For instance, I have a relative who converted to Catholicism as an adult. Her childhood was the inspiration for Four-Girl. She was born on a bad day, and because of that, her grandfather hated her. She couldn't find a place for herself in Chinese stories, so she had to look elsewhere. I debated about which saint to use. I settled on Joan of Arc because of how similar her story is to the Boxers. She's living in a country under siege by a foreign power, and she's invested with a spiritual power that inspires her to fight that foreign power. Lark Pien did the color for both books. Did you talk about the palette together? That seems so essential to the continuity of the historical events shared by the two books, and also in the way the spiritual transformations of the two protagonists are conveyed. We had a lot of conversations about that. Lark is a really accomplished cartoonist in her own right, with books such as Long Tail Kitty [Blue Apple, 2009]. I knew that the scope of each book would be different—even the physical geography would be different. The Boxers went on a long journey to the capital, and the villagers for the most part stayed put. I knew the books wouldn't match up in terms of scope, and I wanted Lark, with her colors, to indicate that. I gave her lots of pictures of Chinese Opera. We wanted those battle scenes to be bright and colorful, and for Boxers to read like an epic. We wanted Saints to be more personal, like autobiographical comics--they're often monochromatic, one or two colors, most done in French gray. We talked about how Joan of Arc had to seem like she was coming in from another world, as if she'd just stepped out of a European illuminated manuscript. Sometimes the cultural clashes were simple misunderstandings, weren't they? The incident where Little Bao meets German soldiers [on the road] was based on an actual confrontation between Chinese villagers and German soldiers. It was a fight about the right of way. The Chinese understanding was the person with the larger load had the right of way; the Germans believed that the higher rank had the right of way. It ended up becoming a bloody incident. One of the most heartrending scenes in the books involves the Hanlin Academic Library. Tell us more about that. The burning of that library was tragic. A lot of stuff was lost in that fire that we'll never have again. The Europeans left it unguarded, and the Boxers burned it down. And it was the European scholars who tried to save that library. Chinese history is very complex. If you look at China in the last 100-200 years, it's vacillated between clinging too tightly to the past, and trying to get away from history completely. Around the turn of the [20th] century, there was this holding on to the past that weakened China and maybe made them fear Western technology. During the Cultural Revolution they were trying to excise the history, and it caused tremendous pain. That's a driving part of that section of the book. You can't get away from your history; you can't burn down your own libraries. What's next for you? I have a book coming out next year that I did with Sonny Liew, an artist from Singapore. I wrote it after Boxers and before I finished Saints. I wanted to write a more uplifting story. I found a link to a blog, where they highlight Golden Age characters, and I discovered a superhero named Green Turtle, created by one of the first Chinese artists in the 1940s, Chu Hing. The rumor is that he wanted Green Turtle to be Chinese American. The main character's face is almost always obscured. Sonny and I are telling his origin story. Listen to Gene Luen Yang reveal the stories behind Boxers and Saints, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing