A Renaissance Woman| Up Close with Nikki Grimes

Photo by Aaron Lemen

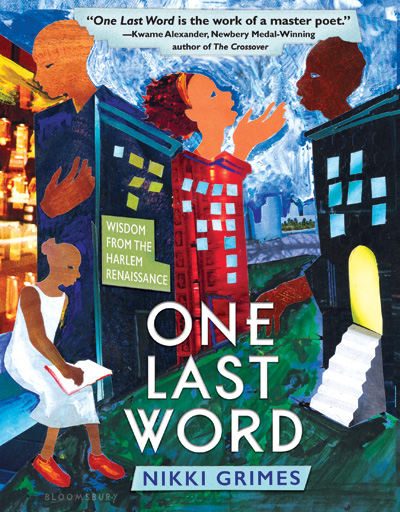

In her latest book, One Last Word: Wisdom from the Harlem Renaissance (Bloomsbury, Jan. 2017), Nikki Grimes draws upon the words and sentiments of an earlier age to create a rich and textured mix of vintage and original poems, illustrated by a dazzling array of African American artists. We are thrilled to hear what the author has to say about this ambitious and heartfelt project.

So much of your work affirms the experiences of today’s young people and encourages them to find their own voices. Why did you choose to look to the voices of the past for this endeavor? When I was 13 years old, I gave my first public poetry reading at the Countee Cullen Library in Harlem, New York. It was a perfect venue for me to officially kick off my life as a writer because the poets of the Harlem Renaissance, including Countee Cullen, were a huge inspiration to me as a young black poet. These masters wrote honestly and authentically about struggle, which certainly resonated with me. But they also wrote about hope, of which I was sorely in need. We currently live in a time of great struggle and social injustice, and once again hope appears to be in short supply. In that sense, the words and voices of the Harlem Renaissance poets are as relevant and necessary to today as they were to my generation. It seemed only natural to revisit the work of these masters for the wisdom they have to offer.

What is it about these words, written nearly a century ago, that seems vitally important to remember today? There’s a boldness and a clarity about this poetry that’s especially appealing at a point in time when we need to cut through the noise of our age. At the same time, there’s a respect for the beauty and nuance of the English language, which we’re in danger of losing amidst our youth’s current fascination with abbreviated, 140-character quick speech. Emoji’s rule, and the lushness of language, the artful turn of phrase, the masterful use of metaphor is dangerously close to the literary chopping block. I want to entice young readers back to a love of language. I believe the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance can help me achieve that.

How did you know that the “golden shovel”* was the perfect way to revisit these master poets’ work? I didn’t know that it would be perfect, but I did believe that the form provided the perfect excuse for me to revisit and reimagine the poetry of these masters. The form is exquisitely challenging, and I do so love a good challenge! By introducing it in a few workshops over the years, I’ve discovered other writers—including upper elementary and middle school poets—relish the challenge, too.

You have clearly mastered the form, but it must have taken quite a bit of time and creative energy. What keeps you inspired and focused? The work felt important, and while it required a Herculean effort, creatively speaking, it was simultaneously energizing. I’m not sure how both things can be true, but there you have it. Besides, I’m far too stubborn to give up on a project simply because the work is mind-bending. And the words themselves kept me on track. The striking lines I chose from each of the original poems became codes that I had to break. Concentrated focus was the only way to accomplish that, and having had success with my first golden shovel poem, I knew success was possible again, if I just stuck with it.

Poetry and spoken word seems to be having a bit of a renaissance, especially in our popular culture. How do you think schools can capitalize on this and embrace the power of language and the multitude of ways it can be used? It starts by sharing poetry throughout the curriculum. The marketplace is so rich in poetry right now that one can find poetry with which any student can relate. If your students love sports, try collections of poems about baseball, or soccer, or novels-in-verse featuring basketball. There are themed collections about history, science, even math. You name the subject, there’s likely to be at least one or two collections or verse novels on that topic. Beyond that, try reader’s theater, open mic poetry in the classroom, poetry readings, and poetry slams. Some of these are already being experimented with in classrooms across the county, and to great effect. Teachers who are using poetry and novels-in-verse with their students, and inviting them to write and perform poetry of their own, tell me that the culture of their classrooms is changing. As students share their work, revealing themselves to one another, they’re beginning to develop a greater respect for poetry, for language, and for one another. Through poetry, they’re discovering that they are more alike than they are different. That’s an enormous payoff for bringing poetry into the classroom.

Poetry and spoken word seems to be having a bit of a renaissance, especially in our popular culture. How do you think schools can capitalize on this and embrace the power of language and the multitude of ways it can be used? It starts by sharing poetry throughout the curriculum. The marketplace is so rich in poetry right now that one can find poetry with which any student can relate. If your students love sports, try collections of poems about baseball, or soccer, or novels-in-verse featuring basketball. There are themed collections about history, science, even math. You name the subject, there’s likely to be at least one or two collections or verse novels on that topic. Beyond that, try reader’s theater, open mic poetry in the classroom, poetry readings, and poetry slams. Some of these are already being experimented with in classrooms across the county, and to great effect. Teachers who are using poetry and novels-in-verse with their students, and inviting them to write and perform poetry of their own, tell me that the culture of their classrooms is changing. As students share their work, revealing themselves to one another, they’re beginning to develop a greater respect for poetry, for language, and for one another. Through poetry, they’re discovering that they are more alike than they are different. That’s an enormous payoff for bringing poetry into the classroom.

I understand that this is the first time you have contributed one of your own pieces to illustrate an anthology. Was that scary? The scariest. Not only was this my first attempt at illustration, but my humble work was to be displayed alongside the work of many of the finest, most honored African American illustrators working today. I should know. Many of them have illustrated some of my books, and these artists were drawn from my very own wish list. What was I thinking? But once I had committed to the project, I had to push past my fear.

What other fun, creative, and brave projects do you have in the works? I’m in the final throes of completing a companion to Bronx Masquerade, which is rather scary. Creating a follow-up to a successful novel is always daunting, I think. In addition, I have a second project forthcoming in which I make use of the golden shovel form, yet again. This time, it’s a picture book treatment of Psalm 121, titled The Watcher, illustrated by Bryan Collier. There are a couple more projects I’m toying with, but there always are. I don’t mind walking into my fear, but risk boredom? Never!

*RULES FOR THE GOLDEN SHOVEL: Take a line (or lines) from a poem you admire. Use each word in the line (or lines) as an end word in your poem. Keep the end words in order. Give credit to the poet who originally wrote the line (or lines).

Add Comment :-

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing