The Printz Grows Up: High Points in the History of an Influential Award

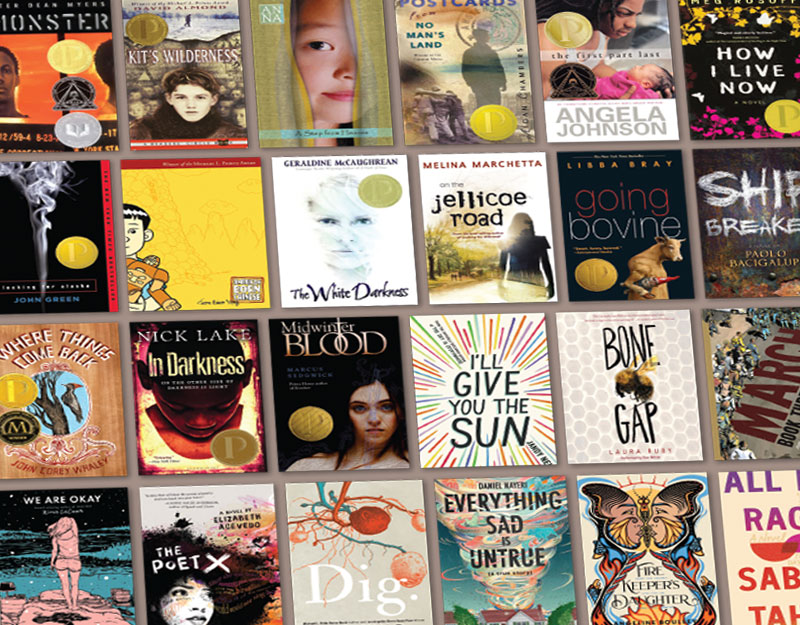

In its nearly 25 year history, the Printz has recognized literature that pushes boundaries and showcases diverse voices. Here are some highlights.

"I think we all knew that the award would change the landscape of the literature.”

Twenty-three years later, that seems an understatement.

|

Walter Dean Myers2001 Bookfest screen grab. Public domain image. |

It’s what Adela Peskorz, professor emerita at Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, MN, was thinking while serving on a brand-new award committee that debuted in 2000. The American Library Association (ALA) had decided to honor the best books for teens with a medal named after school librarian Michael L. Printz, who was passionate about young adult (YA) literature.

In its nearly 25 year history, the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature, sponsored by the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) in conjunction with Booklist, has recognized literature that pushes boundaries, takes risks, breaks new ground, and showcases diverse voices.

It has helped define and shape YA lit, crowning new classics, expanding and transforming the canon, while highlighting outstanding works in a growing field. A look at the history of the award, criteria for selection, and standout titles through the years shows how writing for teens grew to be a multifaceted, sophisticated, and wide-ranging category in its own right.

A brief history of YA

A brief history of YA

While books with teen characters had long existed, Maureen Daly’s Seventeenth Summer, published in 1942, is widely considered one of the first YA novels. Fifteen years later, in 1957, the Young Adult Services Division (YASD, now YALSA) was created to provide professional development connections and advocate for teen library services. The growth of books for teens boomed in the 1960s and 1970s. In the years before the Printz came around—the late 1990s—YA lit was entering its second golden age.

In its relatively brief history, YA lit has undergone vast transformations, evolving from many didactic stories modeling moral virtue and problem novels focused narrowly and often melodramatically on social concerns (think sensationalized looks at the ruinous consequences of drug use, divorce, and teen pregnancy) to the rich, innovative works of today. YA lit is now a thriving and increasingly inclusive world populated by stories in every genre. It’s full of bold choices, strong worldbuilding, fully realized characters, thoughtful examinations of identity and purpose, diverse representations, and endless experimentation.

Criteria

How does the committee, which selects one winner and up to four honor books, choose? Unlike the Newbery or the Caldecott—which each have manuals in excess of 70 pages—the Printz has a compact, flexible outline. One criterion set in stone: To be eligible for a Printz, books must be aimed at ages 12 through 18.

Because of that specification, Peskorz says, many books could not be considered that first year.

|

Adela PeskorzPhoto courtesy of Adela Peskorz |

“I can’t begin to describe how frustrating that was,” she says. “The hope was that publishers would reframe how they market titles and expand their interpretation of YA lit to address the maturity and intelligence of the full range of readers.”

That’s exactly what happened. The shift in marketing and recognition of teen readers “most meaningfully changed the literary landscape,” Peskorz says, “and had a huge ripple effect in expanding the range and quality of titles within the canon well beyond award recipients.”

The award looks to honor literary excellence, however the committee defines it, and embraces the idea that the literature itself, and changing times, may alter and elucidate the very definitions of excellence.

Encouraging experimentation and diversity, the Printz doesn’t mind controversy. “In accordance with the Library Bill of Rights, CONTROVERSY is not something to avoid,” the criteria states. “In fact, we want a book that readers will talk about.”

In 2022, ALA tracked 1,269 attempted book bans, and in 2023 hardly a day goes by without news of censorship attempts in schools and libraries across the country. So it’s significant to have an award for YA lit that embraces controversy and acknowledges the whole experience of humanity.

The Printz looks to spotlight the importance of this field and inspire wide readership. Here’s a look at its legacy so far.

Year 1: setting the tone

Year 1: setting the tone

Being part of that first committee tasked with choosing the inaugural award and honors, Peskorz says, “There was a combined sense of both nervous excitement and weighty responsibility attached to what I (and others) saw as a sea change in the world of YA literature. For the first time the canon, and by extension its intended readers and audience, was being legitimized, respected, and elevated to a level long overdue.”

The selections that year largely valued innovative format and structure. The winner, Walter Dean Myers’s Monster, has a screenplay format with journal entries and pictures.

Ellen Wittlinger’s honor book, Hard Love, features zine pages, poems, letters, and diary entries. Laurie Halse Anderson’s honor title, Speak, features short scenes structured around the seasons of a school year. The third honor book, David Almond’s Skellig, about two young kids and their magical, mysterious new companion, follows a more traditional format. Almond won the Printz award in 2001 for Kit’s Wilderness.

“It really mattered to me to receive the honor and the award,” Almond says. “Confirmation that I was on the right track. I like the seriousness of the Printz approach, the understanding that writing for young people has profound literary value and should be at the heart of our culture.”

Peskorz notes that her committee chose books that mostly broke from straightforward narrative structure. “I think that pattern has continued in incredibly creative ways over time: unreliable narrators, mixed media and communication devices, alternating voices, and so much expansion in the ‘conversation’ of literature in ways that challenge and excite readers.”

“They each celebrated complex ways the literature could speak to and for our readers, and all reflected a willingness to take risks and respect the intelligence and sophistication of their readers,” she says. Indeed, that year’s books helped set the tone for the decades of literary excellence to come.

|

The 2016 Printz committee with Bone Gap award-winning author Laura RubyPhoto courtesy of Lalitha Nataraj |

A crash course

|

A legacy of challengesPrintz winners and honor titles have been banned, challenged, or restricted from the start. Both the 2000 winner, Monster by Walter Dean Myers, and honor book Speakby Laurie Halse Anderson have also been the subject of censorship attempts. Last month, Anderson donated $100,000 from her Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award prize to support PEN America’s work tracking challenges and bans and fighting censorship. Other Printz titles that have been under fire include John Green’s 2006 winner, Looking for Alaska (for sexual content), 2015 honor This One Summer, written by Mariko Tamaki and illustrated by Jillian Tamaki (for drug use, language, and sexual content); 2016 honor Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez (for being sexually explicit and depicting abuse); 2018 honor book The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (for violence, profanity, and being seen as promoting critical race theory and anti-police messages); and 2019 winner The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo (for being anti-Catholic). “Given the fraught sociopolitical climate including attacks on libraries and the freedom to read, it seems apt to revisit the award criteria by asking committee members to explicitly consider diverse representation of experiences in the assessed literary works,” says 2016 Printz committee member Lalitha Nataraj. “The Printz criteria do not aim to promote any message or shy from controversy. But I would argue that it’s not controversial to recognize books that illuminate marginalized voices and critique systemic inequities.” |

The award’s history doesn’t yet span 25 years, but its picks represent an astonishing cross-section of life and literature: Gothic horror, fantasy, sci-fi, contemporary, historical fiction, romance, adventure, psychological thrillers, reimaginings, folklore-steeped stories, dystopias, surrealism, and paranormal.

American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang, which tells the stories of three Chinese and Chinese American characters exploring identity, acceptance, and stereotypes, won the 2007 medal and was the first graphic novel recognized by the Printz committee, just seven years into the award’s history. By contrast, the Newbery took nearly 100 years to award a graphic novel the winning medal, with Jerry Craft’s New Kid in 2020.

Virginia Euwer Wolff’s True Believer (2002 honor) and Helen Frost’s Keesha’s House (2004 honor) were the only Honors in those early years to use a then relatively rare format, verse. YA verse novels have since exploded in popularity; winners and honors in 2018 through 2022 all include a novel or memoir in verse.

Though the award heavily favors fiction, it has also recognized poetry, memoir, nonfiction, biography, and a short story collection. The 2023 honor book Queer Ducks (and Other Animals): The Natural World of Animal Sexuality, by Eliot Schrefer with illustrations by Jules Zuckerberg, is about same-sex animal behavior and the nature of queerness. It’s one of the few nonfiction books ever honored.

Memoirs have made the list only a few times, too. The first to be recognized, Jack Gantos’s Hole in My Life, honored in 2003, recounts a fateful decision by young Gantos that led him to be captured by the FBI and imprisoned.

There are also genre-defying titles in the Printz lineup, such as Laura Ruby’s inventive 2016 winner, Bone Gap, about a kidnapping, a netherworld, and face blindness. Told with a meld of story types and alternating viewpoints, it defies categorization.

Stories take place all over the real world and many fictitious ones. Many are set around schools, including YA powerhouse John Green’s debut, Looking for Alaska, about love, grief, and last words, which took the 2006 medal. The milieu for a Printz-winning novel can truly be anywhere, including an underground bunker during an apocalypse where giant praying mantises run wild (Andrew Smith’s 2015 honor, Grasshopper Jungle).

Popular themes and topics? Hope, survival, suicide, murder, punk rock, road trips, death, grief, religion, faith, racism, sexual assault, loneliness, love, feminism, mental health, gun violence, addiction, rage, abuse, and intergenerational trauma, to name more than a few.

A.S. King’s surreal, multigenerational story Dig, the 2020 winner, delves deep into racism, white privilege, secrets, trauma, and family dysfunction. Like so many other award-winning titles, Dig is a challenging, sophisticated novel that respects teen audiences as capable, eager readers of labyrinthine stories and demanding subject matter.

The stories are narrated by an eclectic group, including teenage fathers, demons, interdimensional monsters, immigrants, refugees, characters surviving a terrorist occupation, runaways, victims of kidnapping, and heretics.

The 2010 winner, Going Bovine by Libba Bray, features a main character recently diagnosed with Creutzfeldt-Jakob (“mad cow”) disease on a quixotic journey with a yard gnome sidekick. In Nazi Germany, Death himself narrates the extraordinary 2007 honor title The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, originally published as a title for adults in Australia.

Some books have one character narrate, many have alternating perspectives, and a handful, multiple narrators. A group of unraveling children share storytelling duty when their nihilist classmate climbs a tree and refuses to come down in the 2011 honor book, Nothing by Janne Teller, translated from Danish by Martin Aitken.

While most committees chose the full docket of four honors, a handful have only picked three, and in 2016, when Ruby’s Bone Gap won, the committee only chose two: Ghosts of Heaven by Marcus Sedgwick and Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez. Lalitha Nataraj, social sciences librarian at California State University at San Marcos and member of the 2016 committee, says, “I appreciated our committee’s firm decision to only name two Honor winners; it was a tough decision because we suspected (rightly so, I think) that people would be mystified or even angered by this.”

Nataraj adds that the 2016 selections were united by “stunning and emotionally resonant prose,” and she found it notable that a large committee with varied tastes could so strongly be drawn to just three titles.

Recognized twice, or thrice

Twelve authors have won two awards, including M.T. Anderson, who took honors for both books in the “The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation”duology, in 2007 (for Volume 1: The Pox Party ) and 2009 (for Volume II: The Kingdom on the Waves). Sedgwick is the sole author to have won three Printz awards: Revolverreceived an honor in 2011, while Midwinterblood took the medal in 2014 and The Ghost of Heaven won a 2016 honor.

Those books awarded Printz medals and honors are often heavily decorated with wins from other awards, too, including the Carnegie Medal, William C. Morris YA Debut Award, Stonewall Book Awards (Mike Morgan and Larry Romans Children’s and Young Adult Literature Award), Pura Belpré Award, National Book Award, Coretta Scott King Book Award, American Indian Youth Literature Award, and Asian/Pacific American Book Award. They also appear on countless best of year lists. And two books have taken home a Printz Honor and a Newbery Honor: Gary D. Schmidt’s 2005 historical fiction work Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy and Long Way Down, Jason Reynolds’s 2018 verse novel.

Most recently, in 2023, Sacha Lamb’s When the Angels Left the Old Country, a queer immigrant tale set in the early 20th century and steeped in Jewish folklore, about an angel, a demon, and many humans looking to start new lives in America, won a Printz Honor, Stonewall Award, and the Sydney Taylor Book Award (for works portraying the Jewish experience). Lamb says, “I hope that the Printz recognition for a book like this, that combines explorations of gender and sexuality and a deep Jewish cultural context, will encourage more authors and editors to bring out books that tackle intersectional identities without compromise.”

|

The 2023 Printz committee watches Sacha Lamb’s acceptance speech for the honor title When the Angels Left the Old Country.Photos courtesy of Levine Querido |

Where to from here?

While YA has flourished since the award’s inception, there’s still new ground to be broken. Areas for growth include awarding more medals to nonfiction, honoring an anthology, and elevating the voices of trans and nonbinary stories and creators.

Characters in Printz books also tend to skew older. Despite that criteria that books be for ages 12 to 18, upper middle grade or lower-aged YA is generally underrepresented. Schmidt’s Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, Everything Sad Is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri, Starfish by Lisa Fipps, and both of Almond’s books stand out as exceptions.

The most significant change in recent years in books recognized by the Printz and the field of publishing itself is the valuing of diverse voices and stories. Though the Printz has modernity on its side and got off to a strong start, with Walter Dean Myers, who is Black, winning the medal in 2000, it took a while for the award to start recognizing a wide array of authors. Until only about seven years ago, 80 to 100 percent of honored authors each year were white. In recent years, that number maxes out at 60 percent. In the coming years, the Printz-worthy canon will continue to reach new horizons with content, format, and identities represented and authorial voices included. “We want a book that readers will talk about,” the criteria note. For nearly 25 years, committees have provided plenty of incredible selections to do just that.

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library and blogs for “Teen Librarian Toolbox.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!