South Carolina State Superintendent Seeks Control of Library and Classroom Collections

South Carolina Department of Education drafted a new regulation that would give it authority over school and classroom libraries.

Banned Books Week may be over, but the fight for control of school library collections continues in districts across the country. In South Carolina, the state's Department of Education (SCDOE) wants to step in.

The SCDOE has drafted a proposal for a new regulation that would give the state, not local school boards, authority over school and classroom library materials. The South Carolina Association of School Librarians (SCASL) disagrees with the change, believing material selection policies should remain at the local level via district and school-approved policies.

|

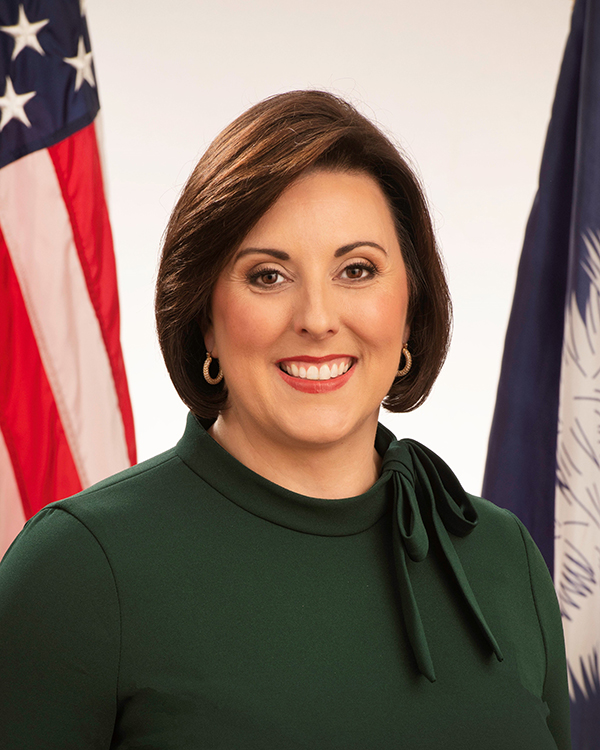

South Carolina state superintendent Ellen Weaver |

SLJ reached out to the SCDOE spokesperson about why this change is necessary, but has received no response. The proposal is another move in the increasingly deteriorating relationship between South Carolina state superintendent Ellen Weaver and SCASL.

In August, Weaver cut ties with SCASL, ending a 50-year working relationship without warning. Events previously cohosted will be run strictly by the SCDOE, and the superintendent will reach out to the state’s librarians individually instead of through its member organization, according to the SCDOE spokesperson.

The announcement that the state was severing ties was the first time that SCASL members had heard from Weaver since she recorded a welcome video for their annual conference in March. In that message, she told librarians she was grateful for their work and looked forward to seeing them soon. She also shared a story of an encounter with Banned Books Week honorary chair LeVar Burton.

“He is as passionate a champion of libraries and books as he was when I was growing up watching the show, and so I just want you to know that we are so grateful for the work and the time that you invest into your schools, into your into your libraries, and most importantly, into the students who you serve,” she said in the recorded message in March. “I hope you have a wonderful conference, and I look forward to seeing you soon.”

She never sought a meeting before sending a much different message to the state's school librarians in August.

“SCASL’s August 9th letter to the South Carolina School Boards Association labeled parental efforts to ensure that library materials are age appropriate as [if they are] book bans, censorship, and violations of educators’ intellectual freedom rights,” a spokesperson emailed in response to SLJ asking why Weaver ended the partnership. “SCASL made its position on a critical issue clear in its letter to the SC School Boards Association. It was important for the Superintendent to do the same.”

The SCASL letter, sent to the school boards and administrators in the state, detailed a case in Forsyth County, GA, where the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights ruled that the county’s schools created a hostile environment for students as a result of the way they handled book challenges. The stated purpose of the letter was to “share this case with the administrators and school board trustees in South Carolina so that our schools can learn from mistakes made in Georgia and avoid the unnecessary costs of legal issues. As an organization, SCASL is here to work alongside students, educators, and school districts as the need arises and we have many resources available to assist districts and educators as they navigate the current climate.”

SCASL’s concern, according to one member, is that district policies are followed when a book is challenged.

“That's why we're speaking up,” said the school librarian who agreed to speak under the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution from administrators. “It has nothing to do with a particular book or a particular type of book. We want policies consistently and fairly applied when people have concerns. We also believe all concerns or questions about a book should remain professional and not include any threats or harassment towards school staff, librarians, teachers, or administrators, because that's also something we have seen. That's been very troubling for our organization and its members.”

Over the last five decades, SCASL had helped the state write standards, evaluation tools, and policies. Members will no longer be part of that process, but the state’s school librarians will continue their day-to-day work at schools as before.

“We will continue to work for our state's children and their access to well-funded and well-staffed school libraries,” said the SCASL member. “And our door’s still open in the hopes that we can still work with the Department of Ed office. It was a long-standing, well-working relationship for 50 years, and we did a lot of great things together to help the librarians across the state. We hope [the relationship] can be mended to benefit our children.”

Two weeks after Weaver’s announcement, SCASL president Michelle Spires resigned. By the organization’s bylaws, past-president Tamara Cox assumed the role.

“It is a challenging time to serve as a leader of a library association and simultaneously juggle family responsibilities,” Cox wrote in an email to SLJ. “Michelle needed to focus on her family instead of trying to manage all of the issues that librarians are experiencing right now. We appreciate all that she has contributed to our organization. The SCASL Board members reaffirm our mission and remain focused on our work to serve the children of our state through strong school library programs.”

The actions of Weaver—who spoke at the Moms for Liberty event in Philadelphia in June—put a spotlight on the role and power of state superintendents and how they could become a factor in the continued politicized book battles that librarians face.

In most states, the superintendent of schools—also known as the superintendent of education, superintendent of public instruction, secretary of education, and chief school administrator—is appointed by the governor, the state’s board of education, or the state university’s board of regents (in the case of New York and Rhode Island). But in 12 states, including South Carolina, the superintendent is elected. There are no superintendent elections in 2023, but 2024 will see four states—Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Washington—vote on new superintendents.

Add Comment :-

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing