After #MeToo: Educators Seek Strategies To Teach Students About Consent

With systemic harassment and assault in the news, educators are working age appropriate lessons about boundaries, safety, and sexual assault into the school day.

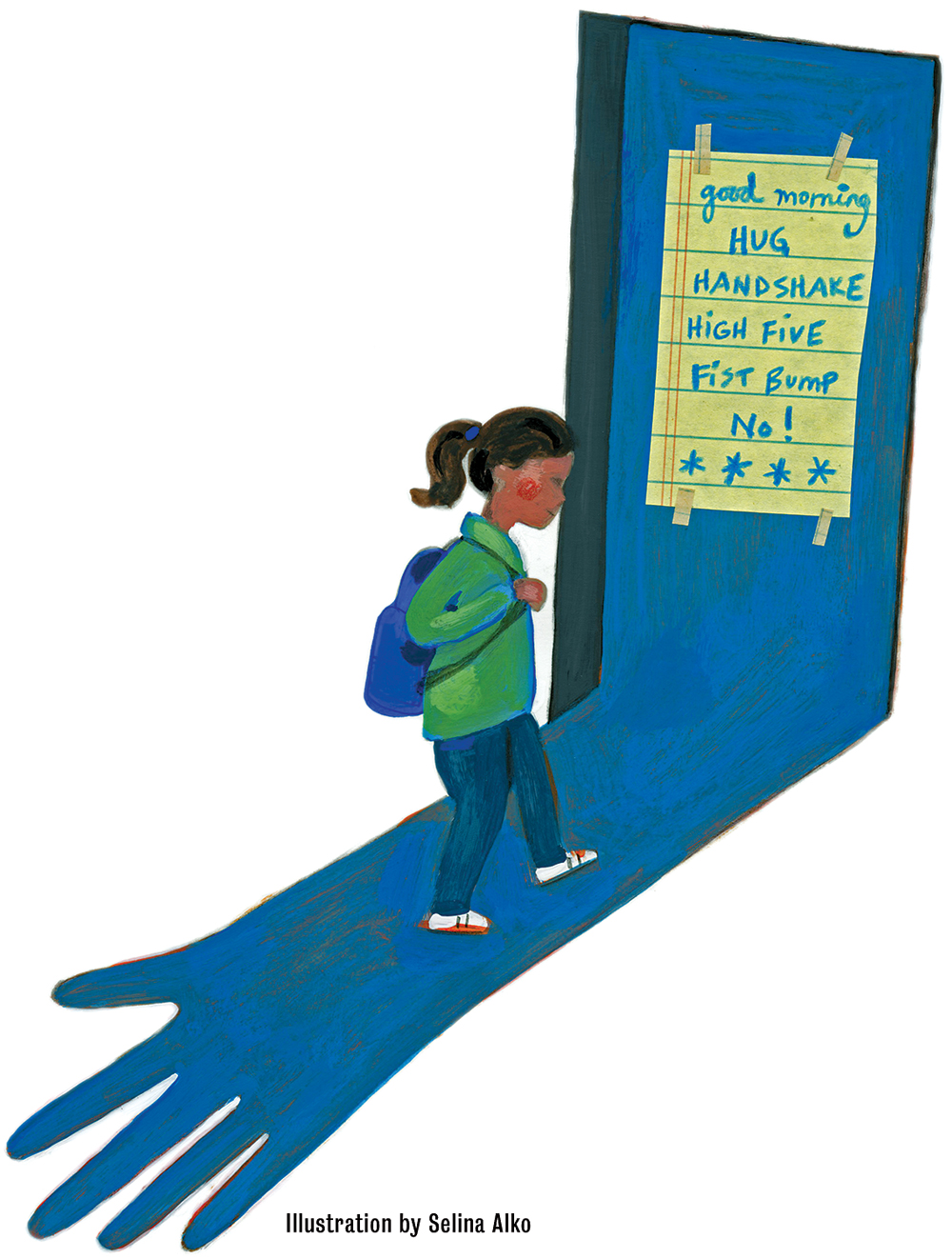

Every school day, first graders stand in line outside their classroom door at P.S. 154 in Brooklyn, NY, waiting to greet the teacher. As they file into the room, each points to their choice on a brightly colored sign taped to the door jamb that lists the words “hug,” “handshake,” high five,” and “fist bump.” My son, a student there, usually picks handshake. He starts the day with his teacher giving him a cordial greeting that respects his mood and boundaries.

Rituals like this, which reinforce young children’s autonomy, personal space, and ownership of their bodies, have become increasingly visible in schools a year into the #MeToo movement. The movement, which has called out routine sexual harassment and abuse of women and girls, also revealed a critical need to help children and teens recognize dangerous behavior and feel empowered to defend themselves.

Also in this article |

Consent—the idea that every physical interaction should be entered into with full agreement from all parties—can and should be taught to young children with age-appropriate terms and methods, according to Jo Langford, a Seattle-based therapist and author specializing in adolescents and sex education.

“If you start young, you understand that it’s not a one-time conversation; it’s an ongoing process,” Langford says. Many teenagers misunderstand consent, he adds. They see it as a box to check before they can have sex. But it actually involves ongoing dialogues about boundaries and permission.

A culture of consent

Broadly, a culture that respects consent also fosters self-empowerment among individuals during personal and professional interactions throughout their lives. Conversations about consent can feel natural to kids who have been taught to respect autonomy and personal space from a young age, Langford says. These lessons can be emphasized through routine family conversations and negotiations: “Just because your brother let you borrow his sweater once, you don’t necessarily get to do it next week.”

While improving physical safety for children requires widespread action from families, government, law enforcement, and society at large, educators can play a significant role. Teachers and librarians can empower children to set boundaries, stand up for themselves, and listen to and respect the boundaries of others. Such lessons teach kids to say “no” to contact that feels wrong, laying the groundwork to address issues on dating, gender dynamics, and assault when they’re older.

Boys in particular must be taught to recognize assault when they perpetrate it and experience it, experts say. Educators need to know what’s appropriate to discuss with minors, and librarians are especially well positioned to provide resources and educational materials for students and their parents. They can also bring in experts to discuss these topics.

The stakes are huge: One in nine girls and one in 53 boys will be sexually abused or assaulted before 18, with two-thirds of those incidents happening to kids between 12 and 17, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) website. Children who have been sexually abused face lifelong consequences, according to RAINN. They’re three times as likely to have major depressive episodes and four times as likely to abuse drugs as adults, among other impacts.

“Everybody’s doing what they can. And because this is a controversial topic and because you’re dealing with minors, everyone tends to tread carefully,” says Karen Jensen, a youth librarian in the Fort Worth (TX) Public Library and founder of the “Teen Librarian Toolbox” blog.

I Said No! Books About ConsentBy Liz Kleinrock

Morrison, Eleanor. C Is for Consent. illus. by Faye Orlove. (Phonics with Finn, 2018). King, Kimberly and Zack King. I Said No! A Kid-to-Kid Guide to Keeping Private Parts Private. illus. by Sue Rama (Boulden Pub., 2016). Sanders, Jayneen. My Body! What I Say Goes! illus. by Anna Hancock. (Educate to Empower, 2016). Kurtzman-Counter, Samantha and Abbie Schiller. Miles Is the Boss of His Body. illus. by Valentina Ventimiglia. (Mother Company, 2014). Cook, Julia. Personal Space Camp. illus. by Carrie Hartman. (National Center for Youth Issues, 2007). Moore-Mallinos, Jennifer. Do You Have a Secret? illus. by Marta Fabrega. (B.E.S. Publishing, 2005) Ludwig, Trudy. Trouble Talk. illus. by Mikela Prevost. (Tricycle Press) Liz Kleinrock (teachandtransform.org) is a Los Angeles–based social justice and anti-bias educator and activist. |

Start in elementary school

In November 2018, a video posted by the Birchwood (WI) School District racked up 4.5 million views and coverage by Good Morning America for its cute demonstration of kindergarteners starting their day in a similar way to the Brooklyn first graders—with their choice of a hug, fist bump, or verbal hello from a morning greeter.

The video went viral for a reason. With stories of sexual assault and harassment frequently dominating the news, many parents and educators want to instill positive messages about consent, early.

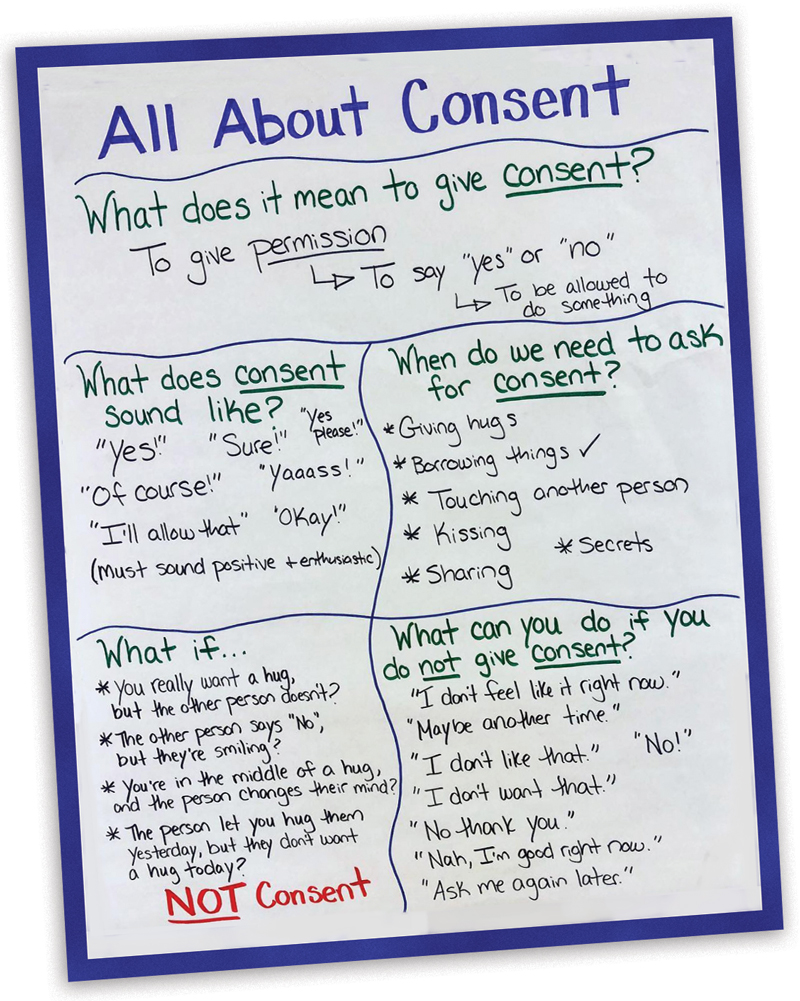

A California teacher received 7,000 likes on Instagram and coverage by CNN for a chart she developed for third grade students that explains consent in terms familiar to eight-year-olds. Liz Kleinrock, who teaches at Citizens of the World Charter School in Los Angeles (see “I Said No! Books About Consent,” p. 23), explained on Instagram that frustration about the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh prompted her lesson.

The chart defines consent as giving permission, explaining that it should sound enthusiastic (“Of course!” or “Yaaass!”) and is needed for actions including touching, kissing, and sharing. It also provides suggestions for what to say when kids wish to deny consent (“I don’t feel like it right now” or “No!”).

“Everyone should be respected no matter what,” Kleinrock says. “There are foundational understandings that need to be developed before sex even enters the conversation.”

Teacher and author Teri Brown was motivated by the #MeToo movement to bring a lesson about understanding the meaning of the word “no” to her after-school program for kindergarteners through fifth graders in Portland, OR, this fall. She read her students the picture book I Just Don’t Like the Sound of No! by Julia Cook, which tells the story of a child named RJ who has trouble accepting it when his parents say no. His teacher helps him understand that he needs to learn how to “say yes to no” by accepting no as an answer and disagreeing appropriately.

“Knowing exactly what no is, and understanding no instead of throwing a fit or continuing to ask or pushing, is the beginnings of teaching consent,” Brown says. “If they understand that, they can understand that they can set boundaries on their own personhood.”

Her students thought the book was funny and relatable. After reading it, Brown engaged them in a series of role-playing exercises and games around saying no and understanding boundaries, like Mother May I?. At one point, she drew circles on the ground and told the children they couldn’t leave their circles while she blew bubbles just out of their reach—a no directive they found hard to follow.

Accepting another person’s no is a crucial part of setting the stage for respect and consent as kids get older, says Seattle-based sex education expert Amy Lang.

“If someone says no, they need to respect the no,” says Lang, who conducts parent workshops and professional trainings about sex education through her company, Birds + Bees + Kids. Lang says that practices such as letting kids choose how they want to be greeted in the morning can be beneficial, but ideally, teachers should guide kids through the process and make it clear that they have the choice to say they want none of the above.

“It looks like an adult saying, ‘Would you like a high five? You don’t have to give me one. That’s cool.’ They see that a safe adult requests and asks first,” Lang says. “Adults need to practice not saying, ‘Oh come on,’…[a]nd there needs to be a little monitoring while they’re learning. That sets the stage for sexual consent.”

Teen hazards, outside expertise

The hope is that by making consent a habit in children, they will be better protected from abuse in adolescence. The teenage years are high risk for girls especially; girls between 16 and 19 are four times more likely than other people to be victims of sexual assault or attempted sexual assault, according to RAINN. Assault by peers is a major concern, Lang says.

Educators working with teens must walk a difficult line. Unless they are health teachers, they should not engage in conversations with teens about sex, according to Lang. But they can direct teenagers to books and resources, and, most important, their own parents, if they raise questions.

“As an adult who works with teenagers, I personally am very careful about talking about sex with [this age group],” Jensen says. “What I like to do is make sure we have books in our collections that address those issues.” She also creates reading lists when important topics are in the news that include statistics and numbers to call if someone needs help. Lang suggests making books for parents available as well.

Jensen’s blog hosted a year of posts, panels, and discussions about sexual violence in YA literature in response to the 2012 Steubenville, OH, rape case in which high school football players raped and photographed an intoxicated, unconscious girl. Jensen also schedules programming in her library regarding sexual assault, though she says it can be hard to gauge what impact it has. She has reached out to local hospitals and invited sexual assault nurse examiners, trained in medical forensic care for sexual assault and abuse, to give presentations about consent and healthy relationships.

Bringing experts into schools and libraries is a way for educators to provide resources to students without crossing improper boundaries. Tamara Cox, a librarian at Wren High School in Piedmont, SC, has invited representatives from a local sexual trauma and child abuse center, Foothills Alliance, to a book club she is planning about the novel Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. The widely read book tells the story of a high school freshman who is raped by an older boy. Her trauma is made worse because she is not able to share her story. The Foothills Alliance representatives can potentially share important context and prevention tools with students during the discussion, Cox believes, while students will learn about an important outside resource.

|

Teacher Liz Kleinrock’s guide

|

Educating boys

“During the Kavanaugh hearings, I had students say to me, ‘Christine Blasey Ford spoke up and people are not believing her. If that happened to me, would anyone believe me?’” Cox says. “Statistically, a lot of people don’t speak up because they’re afraid no one would believe them, and unfortunately the data shows that a lot of times, that’s true.”

Speak is taught in many schools because it gives a realistic account of teenage life and gender imbalances; many also find it empowering because by the end of the story, the victim, Melinda, finds her voice. Eric Divine, a YA author and English teacher in Albany, NY, uses Speak in his classroom for that reason. But he took a break from it when he realized that students in his high school freshman class believed that the victim and perpetrator were equally responsible for the rape.

Divine brought in the school social worker and older students to talk to his freshmen about the reality of sexual assault. But as powerful as the speakers were, he said they were not successful at puncturing the sexist attitudes of some high school students that perpetuate a culture in which assault isn’t taken seriously.

At his school, “Girls are very subservient to boys,” says Divine. “Boys rule the roost in the classroom and the hallways; girls copy them, mimic them, and laugh at dumb jokes that aren’t even funny. They give them that first-class citizenship, and girls have second-class citizenship, and that’s the accepted way.”

He tries to interrupt this gender dynamic by calling out boys on their behavior and pointing out the imbalance. Still, “By the time they’re sophomores, they’re dating. I don’t see girls having a lot of agency in those relationships.”

Teachers have an obligation to address behavior that is at all sexually harassing, in the moment or after the fact, Lang says. When educators point out sexist remarks to girls, it empowers them to stand up for themselves, she notes. It’s especially powerful when male teachers and librarians talk to male students.

“This isn’t a girl problem,” Lang says. “It’s really a boy problem.”

Langford agrees that interrupting boys’ social domination in school environments is an effective way that teachers and librarians can improve dating culture and diminish dynamics that subtly condone harassment and assault. Educators should point out when boys shout out answers in class, and have them practice sitting back and letting girls take the lead. Boys can be given the responsibility to make sure everyone’s voice is heard at school. It’s about empathy and manners, Langford believes.

“It’s time for boys to shut up a little bit and let girls take the front seat,” he says.

It’s also important that boys are given the opportunity to be vulnerable and talk about their feelings, according to Langford. One invaluable takeaway for librarians is that books, including fiction, are powerful when it comes to addressing sexual assault and sexual education.

“Not only can our students see themselves in a character, but the students who have never experienced something like that can empathize with that character,” Cox says. “That can translate to empathizing with those around them who are having that issue in their life.”

At the end of Speak, protagonist Melinda names her rapist and tells her story. Messages of owning your experiences and your narrative empower students, no matter their life experiences. It’s a compelling way for educators to reach students who are vulnerable and navigating difficult social terrain.

“When you care about students, you want them to be able to speak up and share their story and have someone hear them and help them,” Cox says. With the right resources and approach, educators can fill that role.

Drew Himmelstein is a writer and digital editor in Brooklyn, NY.

Relevant Titles for TeensBy Karen Jensen

Saints and Misfits by S.K. Ali Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson and Shout by Laurie Halse Anderson Girl Made of Stars by Ashley Herring Blake Pointe by Brandy Colbert Asking for It: The Rise of Rape Culture and What We Can Do About It by Kate Harding Exit, Pursued by a Bear by E.K. Johnston The Gospel of Winter by Brendan Kiely Moxie by Jennifer Mathieu and The Nowhere Girls by Amy Red The Female of the Species by Mindy McGinnis I Have the Right To: A High School Survivor's Story of Sexual Assault, Justice, and Hope by Chessy Prout Doing It: Let’s Talk About Sex by Hannah Witton Karen Jensen blogs at “Teen Librarian Toolbox.” |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!