Too Good To Be True? Picture Book Portrayals of Police Officers Don’t Reflect Everyone’s Reality | Opinion

We need more titles to counter the single narrative in picture books: Police help everyone. Police catch bad guys. Police keep everyone safe.

My one-year-old daughter is really into trucks right now. One of her favorite books of the moment is I Love Trucks by Philemon Sturges. Every time I read it to her, she points to the trucks pictured in the back and makes me name them. She starts with the one labeled “police truck,” with the description, “A police truck often carries rescue equipment, such as inflatable boats and a giant airbag.”

My one-year-old daughter is really into trucks right now. One of her favorite books of the moment is I Love Trucks by Philemon Sturges. Every time I read it to her, she points to the trucks pictured in the back and makes me name them. She starts with the one labeled “police truck,” with the description, “A police truck often carries rescue equipment, such as inflatable boats and a giant airbag.”

I contrasted that with the police trucks I saw today on my Twitter feed, in the downtown streets of my city—Oakland, California—all weekend, through the massive protests that followed the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Did they contain inflatable boats? I watched video after video, unable to look away, as police shot canisters of tear gas, flashbang grenades, and rubber bullets into crowds of people seven blocks from the building where I usually work, the Main Library of the Oakland Public Library (OPL).

The Main Library is where, in 2017, after the murder of Philando Castile, a group of OPL staff wrote and published Evaluating Children’s Books about Police: a toolkit for librarians and other evaluators of children’s literature. As I wrote in a May 2018 SLJ article, the toolkit asks some questions about the books that exist for young children about police, most of which are either picture books (fiction) or “community helper” nonfiction books meant to teach children about the work of police officers. Those questions include:

Does this book acknowledge the feelings of fear and anxiety children may have on seeing police?

Does this book acknowledge that some people have negative experiences with police officers?

Does the text of this book assert that police only stop people justifiably, without the influence of racial bias?

We did not include a list of “recommended” books for kids about police, books that acknowledged the police oppression experienced by communities of color and depicted police in a way that would feel realistic to a child who had lived experience of police brutality. We stated in the toolkit is that we wanted those who read it to evaluate books on their own and make their own decisions.

We did not include a list of “recommended” books for kids about police, books that acknowledged the police oppression experienced by communities of color and depicted police in a way that would feel realistic to a child who had lived experience of police brutality. We stated in the toolkit is that we wanted those who read it to evaluate books on their own and make their own decisions.

But here's the bigger reason: there weren’t any. Every book we looked at described police as helpers, heroes, someone to trust and call on for help.

I Love Trucks was published in 1999, eight years after video emerged of police beating Rodney King and the subsequent civil unrest. The author, illustrator, editors and art directors involved would have been very much aware of this documented instance of police brutality and the heavy police response that followed.

The text about police in this book—that police trucks “carr[y] rescue equipment, such as inflatable boats and a giant airbag”—aligns with a trend I noticed in other children’s books about police published in 1992 and after. I reviewed 23 picture books about police for the toolkit, acquired through my library system and statewide interlibrary loan. All of them said that police help people, but some tried to further explain police work and got stuck. One book said that police officers have computers in their cars and sometimes ride in helicopters, and that was about it.

Read: Social Justice: Fifteen Titles To Address Inequity, Equality, and Organizing for Young Readers

What’s changed since we published the toolkit in 2017? Very little. Jessica Walker, library aide at OPL, reviewed children’s books released since 2017 and found about half a dozen more that describe police as helpers, heroes, and friends. Despite the evidence to the contrary, we keep telling kids the lie: Police help everyone. Police catch bad guys. Police keep everyone safe.

Librarians, as a demographic, are overwhelmingly white, and when we continue to purchase these books and have them in our collections, we perpetuate the lie. Presenting police as community helpers without a counterpoint available—that police might harm them—is gaslighting for children who see police brutality in their home, in their neighborhood, on TV, and on their parents’ phones.

Of even more concern is the continuous production of picture books with police as friendly characters, including many TV tie-in titles (LEGO, Peppa Pig, Paw Patrol, etc.) and books like I’m Afraid Your Teddy Is In Trouble Today, which I reviewed in the context of our toolkit on Reading While White in 2018. In Teddy, the reader arrives home to find the house trashed and police officers on the front steps, preparing to arrest a naughty teddy bear. It’s all very tongue-in- cheek, and of course Teddy gets released with a warning. As I said in my review, this is no joke for a child who’s come home to find a parent arrested. Who are books like this for? Who’s not going to be in on the “joke?” (Frighteningly, a cursory search on YouTube reveals Teddy as a favorite book for police officer story times.)

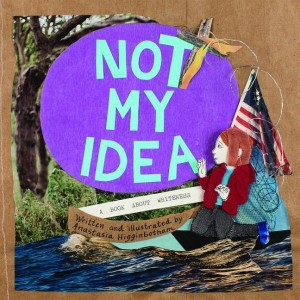

There is one book I’ve recommended many times, published shortly after our toolkit was released. Momma, Did You Hear The News? (above) by Sanya Whitaker Gragg depicts an African American family talking about staying safe with police after a police killing. There’s also Something Happened in Our Town: A Child's Story About Racial Injustice, released in 2018, which does an admirable job showing two families’ reactions to a police killing. These two books are important for library collections. Not My Idea: a Book About Whiteness by Anastasia Higgenbotham (currently available to download for free from Dottir Press) is an excellent example of effective writing for very young children on this scary topic, even though the focus is on a White child’s experience. There are several worthy picture books that deal with incarcerated parents, such as Missing Daddy by Mariame Kaba. Incarceration follows arrest, though, and the trauma of a parental arrest doesn’t have a similar presence in children’s literature.

There is one book I’ve recommended many times, published shortly after our toolkit was released. Momma, Did You Hear The News? (above) by Sanya Whitaker Gragg depicts an African American family talking about staying safe with police after a police killing. There’s also Something Happened in Our Town: A Child's Story About Racial Injustice, released in 2018, which does an admirable job showing two families’ reactions to a police killing. These two books are important for library collections. Not My Idea: a Book About Whiteness by Anastasia Higgenbotham (currently available to download for free from Dottir Press) is an excellent example of effective writing for very young children on this scary topic, even though the focus is on a White child’s experience. There are several worthy picture books that deal with incarcerated parents, such as Missing Daddy by Mariame Kaba. Incarceration follows arrest, though, and the trauma of a parental arrest doesn’t have a similar presence in children’s literature.

What’s still missing are nonfiction books that acknowledge the reality of police violence against communities of color. Books that say:

Police should help people, but sometimes they do not. Police carry weapons and sometimes they hurt people. When that happens, many people get very, very angry. They protest to show how angry they are. You might feel angry at the police, too. It is okay to feel angry. I am very angry.

Amy Martin is the community relations librarian at Oakland Public Library. All views expressed are Martin's own and not necessarily those of her employer.

Read: An Educator’s Guide to Stamped, Antiracism, and You

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!