Building Better Book Fairs: Librarians Create New Models

With a focus on student equity and revenue scenarios, these librarians put their own stamp on book fairs.

|

Maura Madigan hosted a True Book FAIR, a model created by 2023 School Librarian of the Year Julie Stivers. Left: students browse. |

Related reading: |

I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with book fairs. Well, probably more of a like-hate relationship. I inherited an October Scholastic book fair my first year as a school librarian and assumed it was part of the job. Even with tips from the previous librarian and help from volunteers, I was overwhelmed. I could never reconcile the registers with the daily receipts. But most of all, I hated that some kids couldn’t afford books.

The day before the fair, each class came to preview items and make wish lists to bring home. I felt conflicted, imagining students begging their parents for books. I told classes that maybe their parents would say yes, but they might say no, and that was OK. I said I planned to buy many of the books for our library, so they should give me their recommendations.

One student refused to make a wish list because she knew her parents couldn’t buy any books. I had a plan to give out golden tickets to students who didn’t bring money and forgot about wish lists.

Having students make lists of coveted items, knowing some families can’t afford it, is kind of cruel, when you think about it. Each year I tried to make the experience more equitable, using profits to ensure all students chose a book. But kids are smart. No matter how I tried to dress it up, many still considered it charity. At my school, 46 percent of students receive free/reduced lunch benefits. That means nearly half of our families might not have disposable income to spend at a book fair. When I considered the pros and cons of fairs, I concluded the benefits would never outweigh the inequity issue.

I’m not the only educator to think so. Many librarians have pointed out that book fairs contradict what most school libraries hold fundamental—free and open access to books. So why do we still have them? I surveyed 393 school librarians on the topic, using an anonymous Google form, asking what they like and dislike about book fairs. Most respondents still like them, with 63 percent having two to three fairs each year. Here’s what else librarians have to say.

What we like:

Excitement. Asked what they like best about fairs, 196 respondents included the word “excitement” (among staff, students, and families) in their answers. Makes sense—promoting a love of books is a mainstay of the profession.

Profits. Many listed profits as a top benefit. Eighty-seven percent decide how funds are used, including to buy books for the library, author visits, makerspace supplies, and other library-related items or programs. For school librarians with no guaranteed budget, book fairs are often the only way to add new books to their collections.

Home libraries. Students, especially those who don’t visit bookstores, can purchase books to keep forever and share with their families.

Life experience. Some liked giving students the chance to shop and make decisions. I did too. Children have few opportunities to shop on their own and handle money. The fair is a safe environment for them to practice estimating, rounding, and prioritizing.

What we don’t like:

Inequity. For me, this is the biggest drawback. But only 30 percent of respondents agreed with the statement, “I think book fairs aren’t equitable.”

Exhaustion. Exhaustion and resentment at having to run a fair on top of other duties were frequently cited issues. Fifty-seven percent agreed: “I feel exhausted just thinking about the book fair.” Running one, even with volunteers, is a full-time job.

Logistical frustration. Respondents cited issues with Scholastic regarding selection (including limited diverse titles), high prices, low-quality books, non-book “junk” items, and logistical support. But 78 percent still have Scholastic fairs.

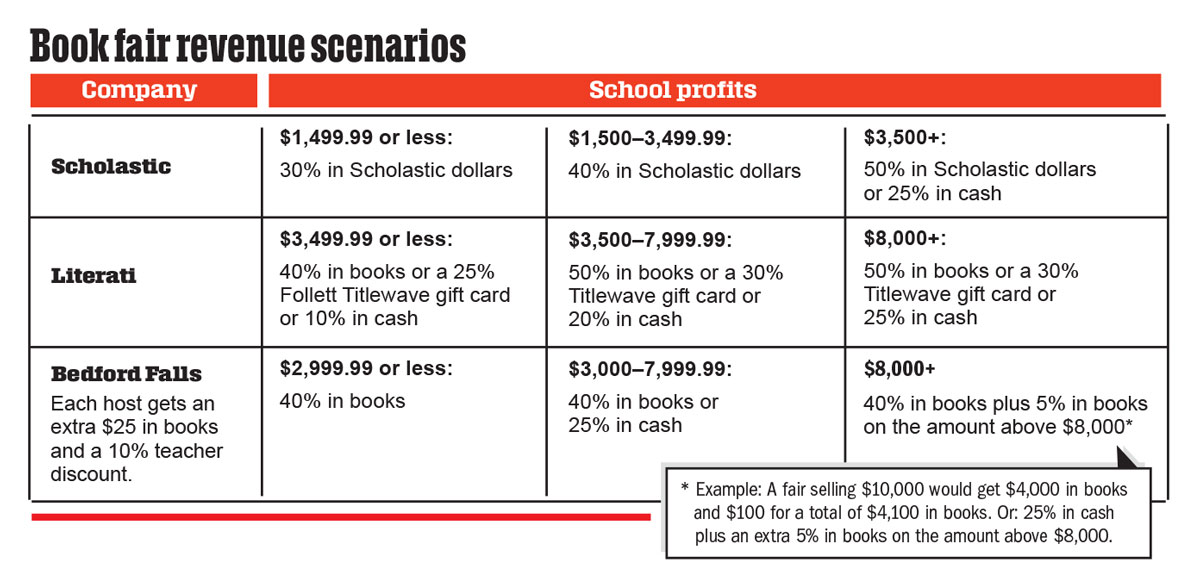

Librarians without a guaranteed annual budget see fairs as necessary fundraisers. I’m lucky to have a guaranteed annual budget so I don’t have to seek outside funding. If every school library had that, would we host fewer traditional fairs? Maybe, but even those with reliable budgets look to fairs for discretionary funds. This amount depends on book-fair revenue. My Scholastic events always sold over $10,000, and I took the profits in Scholastic dollars and cash. Book fair revenue from other schools in my district range from $2,500–$50,000.

Patty Lambusta, a middle school librarian in Virginia, considers book fairs “a necessary evil” to purchase items not covered by the school. But what if there were other ways to generate library funds, spark excitement about books, and let students add to their home libraries, all with less effort and more equity? Would you try them? Here are some options.

Funding and Fundraising Tools |

|

Use these resources to buy books for your collection and source titles for free fairs Dollar General Literacy Foundation First Book Marketplace: Book Bank Laura Bush Foundation for America’s Libraries |

Free fairs

True Book FAIR I was inspired by Julie Stivers, 2023 School Librarian of the Year, to host a free book fair this year. At her middle school, Julie holds two free events annually that she calls “True Book FAIRs.” The early winter fair includes books for younger kids, which students can wrap as gifts for family members. The spring fair has an evening family event where each family member can choose a new book to keep.

Stivers says that the traditional school book fair model “sorts students based on family finances, and no school library should be turned into a for-profit satellite shop for publishers.” She sources books through a combination of school funds, donations from authors, advanced reader copies, and free books from conferences. She buys books from First Book and Scholastic Warehouse sales.

I followed her lead and set a target of two free books per student. My elementary school has about 500 students in pre-K–5, so my goal was 1,200 books. This would ensure each student could choose two, from a decent selection. I met with my principal and PTA officers in September to begin planning our May True Book FAIR. Although I know which books are checked out most, I created a Google student survey to help generate a shopping list. Then I began writing grants. Most books came from seven DonorsChoose grants, totaling over $6,000. I also received a grant from Lisa Libraries for 200 books, a PTA grant, and books from a PTA-sponsored Amazon wish list.

Many parents and their families made generous donations. I surpassed my initial 1,200 book goal, gathering 1,385. The fair ran the week of Memorial Day with students choosing books during their regular library time. Our PTA president, Jen Delboy, created amazing decorations, and parent/grandparent volunteers helped during the fair.

We put a sticker inside each book that said, “This book is a gift from North Springfield Elementary School to:_______________.” After students chose their books, they wrote their names on the stickers. This prevented book mix-ups and let parents know where the books came from. Before the fair, we also had a student bookmark design contest and chose three winners from 87 entries. We printed 200 of each winning design and each student chose one to keep.

Hands down, this was the best book fair I’ve had. Student excitement was high! Several kids chose one book for themselves and one for a sibling. Although it was almost as tiring as a traditional fair, it wasn’t as stressful, because I didn’t have to deal with money. My main concern was collecting new books and thinking of ways to improve next year’s True Book FAIR.

Novel Nation fairs Melissa Corey, 2023 School Librarian of the Year finalist, also hosts free book fairs at Robidoux Middle School in St. Joseph, MO. She has two “Novel Nation Book Fairs” each year, relying on Title 1 funds and grants to purchase enough books so each student can choose three. Although Corey agrees that “traditional book fairs can be huge fundraising opportunities for libraries in need,” she advises school librarians to “ensure that literacy is a right and not a privilege.” Her advice: “Start small, seek out funding, and represent diverse voices.”

Online, in-store, & more

If you must host a fair to raise funds, consider a virtual, in-store, or weekend one. Purchases are private, which many parents appreciate. The virtual and in-store versions are a lot less work for you, and all three options don’t disrupt normal library services.

Love My Library These online book fairs from Read-a-Thon are similar to Boosterthon fundraisers where families are encouraged to register and pledge money. Each student who registers gets a participation prize even if they don’t raise funds. Fifty percent of donations go to students to buy books or other items and 50 percent to the library. Profits can be taken as a Follett Titlewave gift card for books, 75 cents on the dollar in cash, or a combination of each. All orders get sent to the school.

Bookworm Central This small, Virginia-based business offers traditional in-school book fairs locally and online book fairs nationally. The online version lets the school select books, and purchases are shipped to students’ homes. The school gets 15 percent of profits in cash or 25 percent in books with a combination option. A book drive feature allows local businesses and the community to donate money to ensure all students can choose books. Bookworm Central also offers an online bookstore option that generates profits for the school throughout the year.

Barnes & Noble (in-store and virtual): You schedule a date with your local store and it provides vouchers to distribute. Vouchers must be presented at the store, so purchases are credited to the school’s account. Purchases can also be made online using an event ID number. Profits can be taken as a check or Barnes & Noble gift card. Percentages vary depending on total sales, with a gift card option providing a higher amount. For sales up to $1,500, schools receive five percent, and a gift card is the only option. Sales above $10,000 yield 10 percent by check or 15 percent as a store gift card.

Weekend events Moving fairs to after-school and weekend hours give students who can’t participate the ability to opt out. Carolyn Vibbert, librarian at Sudley Elementary School in Manassas, VA, experimented with a weekend fair in 2021, held Friday evening through Sunday afternoon. Her profits were close to those of fairs held during school hours. A main benefit: more family participation.

The library should promote free, open, and equitable access to books for all students. Yes, life can be unfair. Our students will have plenty of opportunities to learn that. They don’t have to learn it in the library.

Maura Madigan is an elementary school librarian in Fairfax County, VA.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!