2024 Margaret A. Edwards Award Acceptance Speech by Neal Shusterman

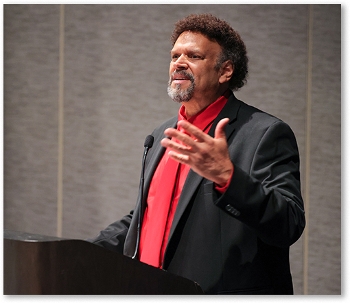

Neal Shusterman received the 2024 Margaret A. Edwards Award, which honors an author "for significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature." The annual award is administered by the Young Adult Library Services Association and sponsored by School Library Journal. Here is his acceptance address, delivered June 30 at the ALA Annual conference held in San Diego.

I’d like to thank ALA/YALSA and School Library Journal for recognizing my work. This is, both literally and figuratively, the honor of a lifetime. The validation of my career, and to be in the company of so many great authors who have won this award – wow!

You know, fiction doesn’t get the respect it deserves. A lot of people dismiss it as frivolous. Especially Young Adult literature. You know that my father never read any of my books? Why? “I don’t read fiction.” He would make special trips to bookstores to turn my books face-out, and put them on end caps—and yet he never read any of them.

But something I’ve come to realize is that fiction is the single most important thing we have as human beings. And I think I have a very compelling argument. I’ll get to that later.

But something I’ve come to realize is that fiction is the single most important thing we have as human beings. And I think I have a very compelling argument. I’ll get to that later.

So how did I get started with this thing that somehow, against all logic, became a career? When did I identify as a writer? When I was eighteen, I bought the Writer’s Market. It lists every publisher, and, to every publisher’s continuing horror, it gives their addresses and phone numbers. I wrote a book when I was eighteen based on a story I told as a summer camp counselor. And then I systematically went through the Writer’s Market, picked about twenty different publishers. (That’s when there were dozens of publishers, instead of just, like, three.) Then, when I was in New York my parents, who lived in Manhattan at the time, I hand-delivered the envelopes with my manuscript to those publishers.

And I received rejections from every single one. If it was current day, I probably would have ignored the rejections and self-published digitally. Which would have been a serious, serious mistake.

Because the book was awful.

Not just bad, but painfully gut-wrenchingly terrible. The kind of bad that gives you a fever just reading it.

Which is my argument against self-publishing. Aspiring writers these days are denied the glorious benefit of soul-crushing rejection. All those form rejection letters that begin “Dear Author…” Twelfth-generation copies, xeroxed so many times that the letters look like ancient runes. Because as painful as those rejections are, we need them. We need to be reminded that we haven’t arrived. And that if you think you have, that’s the proof that you haven’t.

I can tell you right now, I have not arrived. All I’ve managed to do is trick everyone into thinking I know what the hell I’m doing.

It was the rejections as much as the successes that forged my identity as a writer.

My second book, when I was twenty, got me representation. A young, upstart firecracker of an agent nameed Andrea Brown. This book was better than the first, but still not good enough. She couldn’t sell it anywhere, so we had an amicable parting of the ways. It wasn’t until many years later that we reconnected, and she has been a pillar at the core of my career to this very day.

It was my third book that sold when I was 23. Purchased by an encouraging junior editor at Little, Brown. Stephanie-Owens Lurie—one of the greats, who just retired this Spring.

I followed Steph to S&S, then to Penguin, then to Hyperion—before my contracts with her at Hyperion got sold overnight to Little Brown, bringing everything full circle.

I have actually been blessed with incredible editors over the years. Ginee Seo, Rosemary Brosnan, Justin Chanda, Andrea Pinkney, Liz Kozznar and the late, great David Gale. I mean, how lucky have I been to be in the loving hands of the best in the business—all of whom I don’t just see as editors, but as friends, and even family. Editors and publishers who supported me—even when I came to them with the weirdest freaking ideas.

I remember the reaction when I pitched Unwind to David Gale. He said “I have no idea how you’re going to pull this off. But I trust you.” And when I delivered the book, one of his colleages at S&S said “this author is gifted and in serious need of therapy.”

Gifted. I was gifted with publishers who believed in me, and I will never take that gift for granted.

When Unwind—this weird book that was (but wasn’t—but kind of was) about abortion—took off and, bizarrely, found an enduring spot on curriculums around the world, I felt gratitude, and still do, for the people who championed it. The publishers, the librarians, the teachers, and the kids who handed it to their friends—or, perhaps more importantly, to their parents. My favorite comment about Unwind came from a parent who said “My son forced me to read this book so we could discuss it. I never knew my kid thought so deeply.”

When Unwind—this weird book that was (but wasn’t—but kind of was) about abortion—took off and, bizarrely, found an enduring spot on curriculums around the world, I felt gratitude, and still do, for the people who championed it. The publishers, the librarians, the teachers, and the kids who handed it to their friends—or, perhaps more importantly, to their parents. My favorite comment about Unwind came from a parent who said “My son forced me to read this book so we could discuss it. I never knew my kid thought so deeply.”

So there are tons of stories I could tell here today, but I’m sure many of you have already heard them. How my third grade teacher threw me out of the classroom on a daily basis because she was convinced I was special needs – although they didn’t have such nice words for it back then. She sent me to the library to get me out of the classroom, so I became the librarian’s problem. Ms. Judith Shapiro; my elementary school librarian—who turned me into a reader. I went that year from being the slowest reader in my third grade class, to winning the school’s reading award when I graduated sixth grade. Ms. Shapiro came to my parents and me at graduation, with a big old smile on her face and said “I’ve named all my gray hairs Neal Shusterman.”

I could tell stories about where the books that were selected to be honored today came from.

How The Schwa was here was inspired by a kid at a school visit who blended so completely into the background, I went the whole period without noticing his hand was up.

How Bruiser was my response to the pain of divorce, and against cruel unfair expressions like “broken families.”

How Everlost was my first serious attempt at world-building, and as such was more of a rollercoster than Full Tilt—which was inspired by a particularly hellish day at six flags.

How Challenger Deep was inspired by my son Brendan’s experiences with schizoaffective disorder as a teenager. And how trying to make sense of that in words became not just a healing experience for him and our whole family, but turned a dark time in my son’s life into a light to illuminate a subject that needs as much light as it can get. One of the greatest moments of my life was when Challenger Deep won the National Book Award, and I had no speech prepared, so I winged it—and invited Brendan up on the stage to accept the award with me. The winning was great, but what made it special was sharing it with him in the moment. When I went to sit down afterward—I’ll never forget this—my other son, Jarrod, with whom I’ve since written two books—smiles and says to me. “Dad… you’ve arrived.”

How Challenger Deep was inspired by my son Brendan’s experiences with schizoaffective disorder as a teenager. And how trying to make sense of that in words became not just a healing experience for him and our whole family, but turned a dark time in my son’s life into a light to illuminate a subject that needs as much light as it can get. One of the greatest moments of my life was when Challenger Deep won the National Book Award, and I had no speech prepared, so I winged it—and invited Brendan up on the stage to accept the award with me. The winning was great, but what made it special was sharing it with him in the moment. When I went to sit down afterward—I’ll never forget this—my other son, Jarrod, with whom I’ve since written two books—smiles and says to me. “Dad… you’ve arrived.”

But no. I haven’t. That goal post keeps moving. It has to keep moving, because the second it stops, you become irrelevant.

I think I fear irrelevance more than anything else. Because when you’re no longer relevant, that’s when you need to put your pen down. And I never want to put it down.

By the way, Brendan is now living his best life teaching English in Bangkok, and hasn’t had an episode for about 14 years.

I do want to talk a bit about Scythe, which I kind of wrote to disrupt the saturated genre of teen dystopia. I’ve always seen myself as a bit of a disruptor. So Instead of leaning into the trend, and writing yet another story about the world gone wrong, I wanted to explore the consequences of a world gone right. Our best-case scenarios instead of our worst. A world where we’ve defeated disease, and AI isn’t the scary thing we’re all afraid of. I researched all the hopes of AI scientists, sociologists, medical researchers, and it all led me to… life extension—and the inescapable fact, that (unless we destroy ourselves first) we’re going to become immortal. Google’s working on it; Jeff Bezos is working on it; scientists are saying it could be less than ten years away.

So, following consequence after consequence, I came to a world where we live forever and the only way to die is to be taken by the “Jedi of death,” who are dedicated to thinning the population with compassion, and wisdom and love.

And then I’m at my first panel to discuss the book—at the NCTE—and the moderator drops a bomb on me. “What was going on in your life when you came up with this story.”

I was not prepared with that answer. So I had to do some mental calculations, and had an epiphany.

I came up with the idea of Scythe toward the end of 2012. My mom had had a stroke the year before that left her in a locked-in state. One day she was fine, the next she couldn’t move, she couldn’t speak, she couldn’t eat. After the hospital did what little they could do, she was like that in my home for almost a year. Then the hospice doctor finally told my father and me that we really should think about letting her go. There was no hope of improvement. She wouldn’t want to go on like this.

I was the one who had to turn off her feeding tube. For three weeks we held a vigil. And in her final moments, when the nurse told us that it was time, I held one hand, my father held her other hand. We stroked her forehead, we told her that it was okay to go. And she left us.

October third, 2012. It was her 79th birthday.

And in spite of the pain of her passing, there was peace. Because I realized that dying while being held by the people you love is not the worst way to go.

And the very next story I came up with was about people whose job was to end life with love and with compassion. Until then, I had never made the connection. Sometimes we as writers don’t know what it is that compels us to tell a story. All we know is that it’s screaming to be told. Now I knew why I wrote it. It was my way of working through my mother’s death. This author in serious need of therapy found writing to be some of the best therapy there is.

I talked about my identity as a writer. I want to talk a bit about identity in general. Identity is something I’ve given a lot of thought to—especially over the past year. There are three places where our sense of identity tends to come from:

It can be handed to us by those who love us and raised us. Our people.

It can be forced upon us by society. When society says “we don’t care who you think you are. This is what you are.”

Or, when we won’t accept the identity we’re handed, we create a new one. Identity becomes something we choose by looking at the mosaic of who we are, and deciding which aspects of ourselves we will allow to define us.

And identity defines more than just who we are. It defines who we allow ourselves to love, and who we choose to hate. Who we defend, and who we go to war with. Who receives our empathy, and who is denied the slightest shred of our compassion. It defines everything down to the music we like. It allows moms against liberty to call themselves “Mom’s FOR Liberty,” and somehow believe it! Identity defines us, and therefore defines our world.

And you know what.

It’s fiction.

It’s fiction.

It’s a narrative.

Identity is a construct. We take a few of the many, many things that make us who we are, and we say “this is what defines us.” The color of our skin. Our sexuality. Our shared history. Our shared trauma. Our shared language. Every one of those things is real—but the weight we give it in defining us is our choice. And how many times is identity defined in the negative? Not what you are… but what you’re not. Not what you embrace, but what you repudiate. And so, while identity absolutely helps people find their social and cultural family, it also turns everyone else into “other.”

And yet it’s all just a narrative. Isn’t it wild that fiction defines our lives? Which is why I believe narrative is the most important thing we have. And we have to take great care with the stories we tell others, and the stories we tell ourselves.

A lot of my life has been about sitting on fences. Not being indecisive, but deciding that the fence is the only place where you can have perspective instead of blinders. I’ve never really felt comfortable being one thing or the other, and that’s reached into every aspect of my life.

For instance – since the beginning of my career, I’ve often been asked by kids – because adults would be mortified asking—"what race are you?” Or “What’s your mix.” For the longest time my answer was, “I’m a member of the human race. That’s the one I write about. That’s the one the means the most to me.” In recent years I’ve been chastised for that. I’ve been told it’s offensive. Because if you don’t acknowledge and clearly delineate race in your writing, then you are problematic. “Characters presumed white.”

In stood up to that in Scythe and made the world entirely mixed. Race ceases to be an issue. The tone of one’s skin is no more consequential than the color of their eyes. An aspect of who they are without defining who they are.

Through all of this, though, I never realized how deeply cultural ambiguity was woven into who I am.

I have a story to tell you. A narrative about who I am.

Neal Douglas Shusterman, born to Charlotte and Milton Shusterman, November 12 1962. A Brooklyn Jewish family. I was Bar Mitzvahed, and still remember part if not all of my Torah portion. All my grandparents came from Ukraine. My Grandpa Dave, on my mother’s side had Sephardic blood though; he got really dark in the summer, and people often thought he was Black. My parents always said I took after him, but I look more like my father, who had tight curly hair. In the 70’s he had a big old “Jew-fro,” as they called it in those days.

So, I always understood the awkwardness when people tried to parse me out culturally. Such as when I won Ohio’s James Cook Diversity in Teen Literature Award for Challenger Deep—for which, in a carefully worded email, I thanked them for including neurodiversity in their definition.

So that’s who I am.

And you know what?

It’s all bullshit.

It’s fiction, and I do not mean that metaphorically.

On August 20 of 2023—ten months ago—I left for one of my writing cruises by myself. Some of you already know I do this. I take cruises to get writing done. (Deductible – that’s my story and I’m sticking to it.) Sunday, as the ship is pulling out of Miami, I get a text from my son, Jarrod, asking me “Who the hell are these people.”

He just received his results from Ancestry.com. It gives you a whole list of the people in their database you’re related to. On his mother's side, there are people he knows, or at least last names that he recognizes.

On my side, nobody we’ve ever heard of before.

The one who is most closely related—supposedly his uncle, according to ancestry.com—is some guy in rural Maine with Irish/Scottish roots. We follow a link to his personal blog. There’s a picture of him.

He looks like my son Brendan.

We dig deeper into his blog, and we find an entry from two years earlier, in which he talks about something his mom once told him out of nowhere shortly before she died. She told him that she had a baby nearly twenty years before he was born, when she was sixteen… and gave it up for adoption.

The year that happened? 1962. The year I was born.

Okay, so now I have to buy the expensive cruise Wi-Fi, because the ship’s just left the port of Miami. I can’t ask my parents about this, they’ve both been gone for more than ten years. So, I text my cousin Norma. And ask her, “Hey Norma… funny thing… Do you know anything about this?”

Three dots.

For ten torturous minutes.

And then she responds…

“Dearest Neal…”

And I knew from “Dearest Neal” where this was going.

“Yes, you were adopted, but your parents swore everyone in the family to absolute secrecy.”

For 60 years.

And I’m in the middle of the goddamn ocean!

Yeah, so, no writing got done on this cruise.

So what do I know about myself? Well, after a whole lot of sleuthing on the Carnival Mardi Gras, I learned this:

My Irish/Scottish birth mother came from a wild bohemian family of artists in New York. Her mother was an opera singer who played the Mother Abbess in the Sound of Music on Broadway—the one who sings Climb Every Mountain. My biological grandfather played trombone professionally. I have an aunt who was the lead flautist with the Symphony Orchestra in Naples, FL.

And my biological father?

He was a Black jazz musician.

So, biologically, I’m a quarter Irish, a quarter Scottish, half Black, and zero percent Jewish.

And I still remember my Torah portion.

I did consult my rabbi about all this. He said that I’m fully accepted in Reform Judiasm. But for Conservative or Orthodox, I’d need an affirmation ceremony. Which requires three Rabbis and a Mikvah. Sounds like a joke, right? “Three rabbis walk into to a Mikvah…”

So, here’s my new personal narrative that I was able to piece together after exhaustive research:

My birth mother, Diana Kirton had a boyfriend who was also white. But she met a devilishly handsome, and well-build Black jazz kid at a party and, yadda yadda yadda – they were really tired the next morning. (That’s a Seinfeld reference and God dammit, I can still do Seinfeld references. And if you have a problem with that, no soup for you.)

She knew the baby was not her boyfriend’s, and never wanted him to find out. The only person who knew about this was her mother—the mother abbess—who figured out how to climb this particular mountain. They would put the baby up for private adoption to a Jewish family. They even learned some Hebrew and Yiddish to convince the lawyers that they were Jewish and that the father was Jewish.

Why a Jewish family? Well, my friend Thresa was adopted in the early sixties, and she knew the answer right away. In the early sixties, there were a lot of Jewish couples in New York who wanted to adopt. A lot of those were “private adoptions.” And private adoptions basically meant “financial arrangements.”

So, basically, I was probably bought. And there are so many levels to that statement that I am not getting into. But think about this – if there weren’t under-the table financial adoption arrangements in the sixties, my birth mother wouldn’t have carried me to term.

And I wouldn’t be here. So how do I wrap my mind around that?

My birth mother, however, had a stipulation. The baby would be given to the adoptive parents at birth, and no one on my birth mother’s side of the family—not even her—would ever see the baby. Because they knew the baby would be Black, but they didn’t know how black, and she didn’t want her boyfriend to ever find out it wasn’t his.

And that’s how I came into this world and landed on the fence. Although I have a friend who told, me “you’re not on the fence; you’re a bridge.” I like that narrative. I’m sticking to that one. Also, my friend Keith said to me “The universe demanded your presence by any means necessary.” That’s part of my narrative now, too. Because I’m pretty damn happy I’m here.

My old Narrative said I was an only child—but between both sides of my biological family I have six half-siblings. Almost all of whom I am now in touch with.

I recently petitioned my pre-adoption birth certificate. Do you want to know the name my birth mother gave me? I was named after the boyfriend who was not my father. I was born Dennis Lee Smith, Jr. (Not part of my narrative.)

This whole story is a rabbit hole, but I’ve got to talk about my Aunt Millie. My father didn’t read my books—but Aunt Millie read every single book I ever wrote until the day she died at the ripe old age of 93—and she would write me long letters discussing them on pages from a legal pad. And one of those letters recently came back to me, so I went into my file of Aunt Millie letters, and found it.

1997; her letter after reading The Dark Side of Nowhere, which is about a kid who finds out that he’s an alien. Somewhere on page four of her letter, she writes. “The ending was powerful, and really shows what it would be like for someone to find out they were adopted.”

Oh, Aunt Millie. Dear, sweet, Aunt Millie. You missed the point!

No. She had the point all along.

And you know what I found out? Aunt Millie once worked as a legal secretary.

She’s the one who arranged my adoption through her boss.

I wish I could have had this conversation with her—and with my parents.

And remember my newly discovered half-brother who lives in Rural Maine. He’s a published science fiction author! And now we have a contract to write a book together for Simon and Schuster!

The wormhole is endless. And it’s wonderful!

My kids love this. Brendan couldn’t wait to tell his Black friends. Jarrod, always the practical one, says “So… does that mean we're BIPOC writers now?” And my daughters, Joelle and Erin, said “Well, our friends always said you were a Black guy.”

But it does pose a question, doesn’t it? Am I a Person of Color now? If I say no, that’s offensive because I’m denying by biology. But if I say yes, that’s offensive, because it somehow feels opportunistic. Again that question: Fence or bridge?

One thing about learning all this about myself, is that I feel a little more daring when it comes to discussing certain subjects. And I’d like to comment on the whole idea of staying in your lane as a writer. (Because my lane lines go every which way now.)

I believe that every writer. EVERY writer. Should have the absolute right… to write whatever the fuck they want.

Because that’s what creative expression IS! But if you’re going to take on someone else’s perspective you’d better do your homework, and you’d better do it right. Because the way I see it, there are three kinds of diversity, and all three are critical.

- We need books where kids from every underrepresented, underserved group see themselves.

- We need to publish voices from underrepresented groups, and make sure they get to tell their stories.

- Writers need to have the unencumbered freedom to put themselves in other people’s shoes—because the entire point of writing: Putting yourself in perspectives other than your own, so that we can all understand each other better.

We need to remember that third aspect of diversity, otherwise literature suffers, and if literature suffers, we suffer. In the current environment, we would never have had masterpieces like Laurie Halse Andersons Chains, or Tobin Anderson’s The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing. (They’re not related. Not all white people named Anderson are related.)

And it goes all ways. There’s a celebrated Black writer friend of mine who told me she’s exhausted of not being allowed to write stories that aren’t about being Black. She just wants to tell great stories, without constraints.

And how many times have we heard “it’s not your story to tell.”

I get it. But in my heart, I don’t accept that. We are all human beings. Every story is our story to tell if we tell it right—and if we add something of value to the human experience.

So, I challenge the publishing industry to stand up to the restrictive, prescriptive voices out there. Stop enforcing the lanes of limitation and just let us write. I mean, if Jason Reynolds wants to write about Scandinavian Våffeldagen, (I don’t know why he’d want to, but if he does), he should have every right to do it.

So now my life has come full circle in every way. My first award was given to me by a librarian, and now I’m receiving a lifetime achievement award from America’s librarians. My perceived history, has rolled over into to my actual history.

Now I have a whole new perspective on the life that I’ve lived, as well as my life and my career moving forward. Everything passes through this new lens. And yet does any of that alter who I am as a human being. No.

It changes the box that I check on the census. And it gives me a whole new facet of myself to explore. It’s not a devastating thing; it’s surreal, and exciting, and fun. I’ve chosen a narrative in which this is additive to my life. It’s like finding there’s a secret room in a house you’ve lived all your life, and it’s filled with wonderful things. It’s like I’ve walked out of the Truman show… in middle of the ocean, just like he did… and stepped into tomorrow’s unknown.

So, has the work of fiction that is my life changed? Absolutely not.

But now there’s a sequel!

Neal Shusterman is the New York Times best-selling author of over 30 novels for children, teens, and adults. He won the 2015 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for Challenger Deep, and his novel, Scythe, was a 2017 Michael L. Printz Honor book

Read: Neal Shusterman, Dystopian Optimist

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!