10 Ways to Nurture and Nourish Nonfiction Readers

How teachers and librarians have brought nonfiction front and center at their schools.

Once upon a time, nonfiction books were the unsung underdogs of the children’s publishing world. Many adults believed that children prefer fiction. But a growing body of research shows something quite different. It turns out most children enjoy reading nonfiction, and some strongly prefer it.

Once upon a time, nonfiction books were the unsung underdogs of the children’s publishing world. Many adults believed that children prefer fiction. But a growing body of research shows something quite different. It turns out most children enjoy reading nonfiction, and some strongly prefer it.

Nonfiction books can be a gateway to literacy as well as a portal to knowledge. They have the power to fuel a child’s natural curiosity and ignite a lifelong passion for reading and learning.

The good news is that “the quality of nonfiction that’s coming out now is just over the top,” says Meg Medina, the 2023-2024 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. Medina’s platform is ¡Cuéntame! Let’s Talk Books, and she’s deeply committed to making nonfiction part of the conversation.

The National Council of Teachers of English is also advocating for nonfiction. In January 2023, the organization adopted a Position Statement on the Role of Nonfiction Literature (K–12) to shine a light on the critical importance of giving students access to a rich assortment of high-quality nonfiction. The statement strongly supports school librarians and recognizes their important role as literacy leaders.

Here are 10 ways that teachers and librarians can work together to highlight nonfiction at their school.

1. Experiment with shelving

Over a 2-year period, K–12 school librarian Laura Wylie de Fiallos increased the circulation of her nonfiction collection more than 350 percent. How’d she do it? By better meeting the needs of her youngest students.

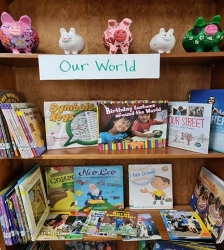

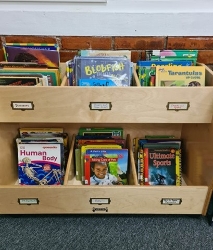

First, Wylie de Fiallos removed all the K–3 nonfiction books from the cramped shelves where they had been in the back corner of the library. After weeding aggressively, she grouped the remaining books loosely by subject (oceans and ocean animals, sports/dance/gymnastics, our world, how things work, etc.) and shelved them in a high-traffic area near the story corner. She displayed as many books as possible with the covers facing out to entice young readers.

First, Wylie de Fiallos removed all the K–3 nonfiction books from the cramped shelves where they had been in the back corner of the library. After weeding aggressively, she grouped the remaining books loosely by subject (oceans and ocean animals, sports/dance/gymnastics, our world, how things work, etc.) and shelved them in a high-traffic area near the story corner. She displayed as many books as possible with the covers facing out to entice young readers.

“If you’re still ‘on the fence’ about your students’ enthusiasm for nonfiction, I encourage you to look at your collection and consider making some changes,” says Wylie de Fiallos. “You have nothing to lose, and your school community has lots to gain!”

2. Add a popular nonfiction section

As a new librarian, PreK–4 school librarian Amy Jent felt frustrated. She spent so much time helping students locate books in their favorite nonfiction series because the titles were shelved all over the library.

But in 2018, she had a brilliant idea: Why not create a popular nonfiction section? She did, and it’s now a place to shelve series like “Who Would Win?” and “Fly Guy Presents” as well as popular titles like the Guinness Book of World Records and a range of books on topics like the military, gaming, and unexplained mysteries.

“Students can find the books they want with little or no assistance,” says Jent, “and shelving is easier because titles don’t need to be in exact Dewey order as long as the books in a series or about a specific topic are together on a shelf.”

3. Promote nonfiction

When Kerry O’Malley Cerra started her job as a high school media specialist, a colleague commented that the nonfiction section “is where books go to die.” Horrified by this attitude, O’Malley Cerra made it her mission to change her school’s mind about nonfiction with a multi-pronged promotional campaign.

After aggressively weeding the collection and adding relevant new titles, O’Malley Cerra used eye-catching book displays and looping slide shows to highlight new titles.

After aggressively weeding the collection and adding relevant new titles, O’Malley Cerra used eye-catching book displays and looping slide shows to highlight new titles.

Since students often congregate in the library before school, she instituted activities like Book Cover Bingo, Title Talk Tuesday, and First Chapter Friday to raise awareness about the library’s holdings.

Have these efforts worked? You bet! The library’s nonfiction checkouts have doubled and now represent about one-third of the total circulation.

“I’m thrilled that circulation data proves my efforts have been successful,” says O’Malley Cerra. “But the true success lies in the number of students who now request nonfiction purchases—biographies, true crime, money-management, philosophy...Kids love nonfiction!”

4. Conduct a book match survey

At the beginning of each school year, elementary librarian Meredith Inkeles gives her grade 3–6 students a genre personality quiz to help them identify the kinds of fiction they like reading most. So when she heard about the Nonfiction Book Match Survey created by literacy professor Marlene Correia, Inkeles was eager to give it a try. This survey goes beyond an interest inventory checklist by asking questions that dig deeper and help students identify the five nonfiction categories (active, browsable, traditional, expository literature, narrative) and formats they like as well as topics of interest.

Some of the students’ responses surprised Inkeles and made her aware of gaps in her collection. She ordered some new books and, when they arrived, was excited to share them with students. She’ll never forget how one sixth grader responded.

“The moment he saw the books, his eyes and smile went wide,” says Inkeles. “You would have thought I was handing over a million dollars and an entire bag of candy instead of three biographies!”

5. Curate preview stacks

Whenever you notice a student struggling to find books they’re passionate about, use the results of the Book Match Survey and what you know about the child to curate a preview stack—a group of books you select with the child’s specific interests, book category preferences, and reading level in mind.

As you hand the customized stack to the student, say something like, “I know you like books about the environment, and I remember your favorite categories are browsable and expository literature. I found these titles just for you.”

This simple act will make a deep and lasting impression on the child. It will show that you understand and honor their unique interests and care about their development as a reader.

For more information about preview stacks, see The Book Whisperer: Awakening the Inner Reader in Every Child by Donalyn Miller (Jossey-Bass, 2009) and Intervention Reinvention: A Volume-based Approach to Reading Success by Stephanie Harvey, Annie Ward, Maggie Hoddinott, and Suzanne Carroll (Scholastic, 2021).

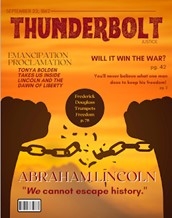

6. Invite students to make magazine-cover book “reports”

Recently, middle school librarian Angie Manfredi collaborated with a seventh grade ELA teacher to offer students an innovative spin on the traditional book report.

After students read a nonfiction book of their choice, they filled out a worksheet to help them identify significant parts of their books and brainstorm ideas for representing the information visually. Then they used Canva to create magazine cover–style designs that incorporated critical content, important dates, and quotes from the book.

Students experimented with using graphics, typography, and language to interest viewers and convey ideas from the books that stood out to them. Some included QR codes on their magazine covers, linking to even more information about their books.

“I was awestruck by the variety of books students selected—cookbooks, world records, biographies, histories, books about animals, and more,” says Manfredi. “I saw their passion for their books in a way that centered their own voice and vision of the work. ... I know we interested students who might have turned up their noses at nonfiction, and we got them thinking about what they read in a much more active way.”

7. Encourage students to share their opinions

When Inkeles received an order of new nonfiction books for her library, she encouraged her fifth and sixth graders to read them and write book reviews that would be added to the school library catalog. After the students read a wide range of sample reviews, Inkeles provided a three-step formula to guide them:

- Open with an attention-grabbing quote, question, or did-you-know fact.

- Answer three questions about the book: Who would enjoy reading this book (age range/grade level)? What is the book about (no spoilers)? Why are the pictures/illustrations important to the text?

- Decide how many stars to give the book on a scale of 1–5.

“I love that students developed a vocabulary for talking about books,” says Inkeles. “Next time, I’ll ask students to include any emotions they felt while or after reading the book and mention any remaining questions they have about the topic. I might also suggest that students recommend additional titles in their reviews. The possibilities are endless.”

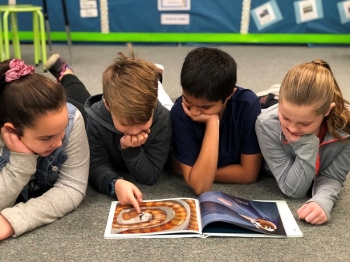

8. Immerse students in nonfiction

After hearing about Inkeles’s book review project, fourth-grade teacher Kim Hines decided to use reviews as the culminating activity in an immersive nonfiction unit that included daily read-alouds, text-feature and text-structure scavenger hunts, and rich-language word searches. Hines also asked students to identify books with expository and narrative writing styles (which sparked some lively debates) and to use Venn diagrams to compare the craft elements in two books.

As students read the books they’d chosen to review, they captured observations about art, design, and craftmanship in note catchers. They also thought about the book’s intended audience and the information they found most interesting.

As students read the books they’d chosen to review, they captured observations about art, design, and craftmanship in note catchers. They also thought about the book’s intended audience and the information they found most interesting.

While students wrote their reviews, Hines encouraged them to play with two or more different beginnings. She also provided a chart-paper checklist to use as a guide.

“I loved this project,” says Hines. “The students did a great job, and they were so engaged. Next year, I’ll move this unit to the fall so that, when we finish, we can participate in the Sibert Smackdown.”

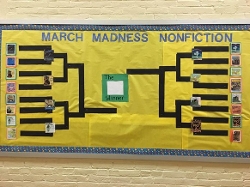

9.Host March Madness Nonfiction

Inspired by the annual March Madness basketball tournament, fifth grade teachers Shelly Moody and Valerie Glueck developed a month-long, school-wide activity in which students read 16 nonfiction picture books (some narrative, some expository literature) and select their favorite. Here’s how it works.

Inspired by the annual March Madness basketball tournament, fifth grade teachers Shelly Moody and Valerie Glueck developed a month-long, school-wide activity in which students read 16 nonfiction picture books (some narrative, some expository literature) and select their favorite. Here’s how it works.

Week 1: Half of the classes reads the eight books on the right-hand side of the board, and the other half reads the eight on the left. Classes discuss the content and structure of the books as well as their favorite features. Then students vote on pairs of books to determine which titles will move on to The Elite Eight.

Week 2: Each class reads the four winning books on the opposite side of the board. Then students participate in rich classroom discussions and vote to select The Final Four.

Week 3: Classes spend time reviewing the four finalists and then vote for the March Madness Nonfiction Champion.

Week 4: Students gather for a whole-school assembly. Following a parade of books that includes one child from each classroom, the winning book is announced. And the crowd goes wild!

“The goal of this event is to inspire curiosity, build background knowledge, and put outstanding nonfiction books in the hands of our students,” says Moody. “It’s hard to capture in words the energy and excitement about books that March Madness has created in our school community.”

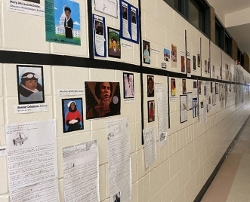

10. Create a school-wide heritage timeline

Because librarian Paula Januzzi-Godfrey’s elementary school serves predominantly Black and brown children from a variety of cultures, she was looking for a meaningful way to celebrate their heritage. When she noticed students had trouble putting people, places, and events in historical context, she envisioned a life-size heritage timeline in the main hallway of the school with content created by the entire school community.

Januzzi-Godfrey’s used black construction paper secured with putty to layout a timeline that began in 1619. At the end, she mounted two mirrors with the words “World Changer,” so students could see that they, too, are part of our nation’s history. After creating some templates, Januzzi-Godfrey invited students and teachers to draw or write about a person or event they’d learned about.

Januzzi-Godfrey’s used black construction paper secured with putty to layout a timeline that began in 1619. At the end, she mounted two mirrors with the words “World Changer,” so students could see that they, too, are part of our nation’s history. After creating some templates, Januzzi-Godfrey invited students and teachers to draw or write about a person or event they’d learned about.

Over time, more and more pieces appeared on the timeline. They featured artists, politicians, athletes, authors, poets, activists, musicians, and others. All genders and people with many shades of black and brown skin tones covered the walls throughout the school.

“I began to notice teachers and students stopping to read items on the timeline,” says Januzzi-Godfrey, “and I received feedback about how much students enjoyed watching the display grow. Most importantly to me, I heard and saw that students and teachers were seeing themselves reflected in the photos on the timeline.”

Have you developed your own awesome idea for highlighting nonfiction in your school? Add a comment. The more options we have for nurturing and nourishing passionate nonfiction readers, the better!

Melissa Stewart is the award-winning author of more than 200 nonfiction books for children, including the Sibert Medal Honoree Summertime Sleepers: Animals that Estivate, illustrated by Sarah S. Brannen. She co-wrote 5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books and edited the anthology Nonfiction Writers Dig Deep: 50 Award-winning Authors Share the Secret of Engaging Writing. Melissa’s website features a rich array of nonfiction writing resources.

RELATED

Tide’s Journey

Whose Footprint Is That?

The Tiniest Giant

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!