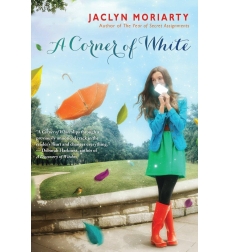

A Corner of White (Book 1 of The Colors of Madeleine), Jaclyn Moriarty

A Corner of White (Book 1 of The Colors of Madeleine), Jaclyn MoriartyScholastic, April 2013

Reviewed from ARC and final ebook

This is a doozy of a book. Clair talked about the difficulties summing up a complex book like The Raven Boys, but that would be a breeze compared to this one. It’s crowded and strange and whimsical but sort of deadly serious and heavy too.

Also, four stars, three year-end lists, two turtledoves and one not-a-list.

Well, not the turtledoves. (The not-a-list is the NPR tagged and searchable assemblage of best titles.)

So does it have a chance? Or, as a fellow librarian asked, is this one of those books that gets stars just because the reviewers don’t know what else to do with it?

Here’s my very short answer: lop off the last section (section 12) and it’s totally got a chance.

Not an undisputed chance — I mean, it’s all speculation anyway, but this is one of those books that I think has potential to polarize, even without getting into the section 12 issue, which I will get to in a bit.

Here’s why this one deserves consideration:

Jaclyn Moriarty writes bizarre, hyper-real or even surreal fiction that seems unbelievable but is at core about serious things. And she’s upped her game here, adding in another world — and such a world! — and dropping the epistolary format she’s used to such great effect in the past for a more hybrid text — there are letters, and they are critical, but there are also excerpts from various other texts, real and imagined (all real in the context of the novel), and lots of third person point of view, usually third person limited. There’s a lot of style, and it’s always on. It’s also incredibly vigorous, which I don’t mean figuratively: if you wanted to teach innovative use of the active voice, you could use passages from A Corner of White, and Moriarty also plays with the concept of who acts (bells ring, rooms retain: this is all totally reasonable, and grammatically correct, but the nouns have more agency than most writers allow them) and uses original, vivid, and often startlingly apt metaphors and similes: “The place flew apart like hands tearing at a jigsaw puzzle.”

Admittedly, a reader might hate the style (and I’ve met some who cannot read any Moriarty book, and especially not this one), but hatred is subjective; the consistency, the linguistic flair, the distinctiveness of voice — these are admirable even if you can’t stand them. I find that they make me think about the language and engage me on a different level as a reader; the style both calls attention to itself and works quite well for the story being told.

But then within all that consistent, stylistically tight writing, Moriarty has created a whole host of characters who have their own distinct voices. Those voices share that hyper-reality (everything is magnified, exaggerated, to comic and poignant effect), but despite that they are indeed distinct. And in Cello, there’s an added element of the bizarre dialect — the Olde Quaintians with their random comparisons, or the princesses with their hybrid speech patterns; even the Farms natives, who seem the least out there of any Cellian citizens, have some quirks of speech that are distinctly their own.

In the World, there are nice parallels between Holly and Madeleine, who sound just a little different from Jack and Belle, but there’s also a similarity of thought pattern among the teens, who sound, well, like teenagers. Early on, there’s a conversation that makes me think of the classic (to us old folks, anyway) Stand By Me Goofy conversation, here about whether the sky they walk under is the same sky as a few hundred years ago, bleeding canker (tree) disease, and even The Matrix. It’s free association, pop culture laced (although, does The Matrix still rate as pop culture? The when of the World sections of this book are little hazy, and these are not entirely average teens, so it would be unsurprising if their pop culture is a little off), slightly pointless, highly entertaining to the speakers and not to the adult listener (Jack’s grandfather) — I am surrounded by conversations like this daily in my library.

And then, continuing my litany of things that are really notable about this book, we’ve got Cello. I think Cello is meant to be the same place Newton’s peers might have thought of as fairy land: there’s magic, for one, and there’s a history of connection with the real world. But that’s pure extrapolation, because Cello is unlike any other concept of a fairyland I’ve ever come across. Bits hark back to other fantasy lands — the Colors were vaguely reminiscent of Fforde’s Shades of Gray, for example, and the odd weather is sort of the inverse of Martin’s “winter is coming” threatened Westeros — so there’s an element of the familiar, a shoutout of sorts to the larger world of imagined worlds in text. But for the most part Cello is its own peculiar self, rife with issues and internally logical even within its illogic. (I’d sort of like to find a crack and visit, in all honesty.) The decision to make Cello mostly modern also allows it to feel weird and other but accessible — my top pick this year, which I’ll be posting about in the near future, is The Summer Prince, and the number one critical complaint is that the world is impossible to imagine for many readers because it’s so far outside our experiences. Cello allows readers to feel oriented.

I mention Newton because he (along with some other historical figures) loom large in the text. There are scientific and philosophical asides all over the place, many of which are paralleled between the worlds: Madeleine talks about Newton and his invention of the cowcatcher train front; the next section has a Cellian train stopping because there are cows on the tracks. Elliot’s father and Madeleine’s are inverse images; Jack and Belle contrast with Elliot’s pack of friends (who, flaw alert, are not very distinguishable or believable); Elliot’s mother and Madeleine’s mother serve to illuminate one another. Often, it seems like there are two books playing out in parallel, but by putting them “in conversation” (as my English Department colleagues would say), each one is enhanced from a thematic perspective. Like the gloss of easy breezy humor over serious issues, this looks like nothing much except two intertwined stories on the surface, but there’s lots of depth lurking below.

In fact, the idea that the two stories comment on one another but are only barely touching might be a metaphor for all of human experience and a meditation on how we learn and think.

I could go on, but instead I’ll point you to the review over at The Book Smugglers blog; the post really captures the smartness and the emotional core.

But there are flaws.

Madeleine comes across as awfully young and naive for a girl who’s been all over the world, attended boarding school with the world’s elite, partied with drugs and alcohol by age 13, and run away 17.5 times. She often seems more like a child than a teen when it comes to emotional resilience. This might make sense; poverty is new and scary and Holly’s health issues are worrying — but something didn’t ring true for me.

Elliot’s friends, as I said, have a sort of fake, storybook quality; they’re a crowd of extras. Again, this might be deliberate, but it’s striking compared to how deeply written Jack and Belle are.

And… it’s first in a series. It ends, with a solid wham of emotional resolution. Elliot’s father is alive, proving Elliot’s loyalty and faith were deserved; Madeleine, meanwhile, has come to terms with the fact that her father isn’t such a great guy. And Madeleine and Elliot have saved one another; her Newton obsession gave Elliot the tool he needed to save his own life (and led to the revelation about his father, which saves him in another way), while the healing beads he sent from the Butterfly Child are what saved Holly, without whom Madeleine would have nothing. And Madeleine has decided to grow up and give up the magic of Cello (although not her belief). It’s an open ending — neither father has been recovered, and so much is left to explore — but it’s the kind of open that doesn’t need another volume, although it allows for one. Emotionally, the story has ended. Anything more is just going to be plot.

And then, bam, section 12. The royal family of Cello is missing. They’re in the world. And Elliot and Madeleine need to save the day.

WHAT?

This rich, emotional and internal journey of a book has just become a blackmail mystery?

(I will note that I’ve actually already read the second book, which is mostly a mystery/adventure in terms of broad strokes, and is excellent, but it’s all about Elliot — or mostly — and the Cellian situation/politics, and it has a very different overall feel.)

There’s nothing wrong with a cliffhanger ending, but this throws the balance that has otherwise characterized the book — and is one of the things I would have pointed to as why this might deserve some recognition by the committee — off. It means all the series issues suddenly matter (we can see that we don’t yet have enough information to answer the questions. Maybe Elliot’s friends will turn out to be awesome and fully realized in book 2. Maybe the parallels are set up for something more. Or not. We can only know that there’s more.)

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!